The Color of Christ Meets a Cast of Critiques: A Response from Edward J. Blum and Paul Harvey

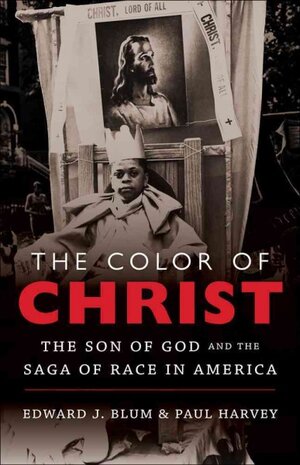

For the last three days, we've been running a series on responses to the book The Color of Christ: The Son of God and the Saga of Race in America, which were given at the 2013 AAR in Baltimore. Our thanks to Kathryn Gin Lum, Joshua Paddison, and Jennifer Graber for their thoughtful and provocative comments -- the links to their names will take you directly to their comments. We conclude the series today with our reactions.

We think Color of Christ

benefits from the combination of “old-fashioned” archival work and the digital resources revolution still with us. Josh Paddison raises some excellent points, and caveats, about how what is or is not available may shape scholarship in ways that are invisible. And certainly, to cite one example, simply doing a keyword search for “Jesus” in the online version of the Jesuit Relations is awfully convenient, but unless you’ve spent

hard time reading and studying the volumes and come to know the personalities

and styles of the individual authors, you are likely to miss crucial parts of

the meanings when you use the computer to find the Jesus needle in the haystack

of words the French Catholic missionaries left behind. And yet, when you can

combine old-fashioned immersion with newfangled digitized searching,

revelations emerge -- as they did when we learned that the famous Cherokee newspaper the Cherokee Phoenix (published from 1828 to 1834) was digitized and available.

We think Color of Christ

benefits from the combination of “old-fashioned” archival work and the digital resources revolution still with us. Josh Paddison raises some excellent points, and caveats, about how what is or is not available may shape scholarship in ways that are invisible. And certainly, to cite one example, simply doing a keyword search for “Jesus” in the online version of the Jesuit Relations is awfully convenient, but unless you’ve spent

hard time reading and studying the volumes and come to know the personalities

and styles of the individual authors, you are likely to miss crucial parts of

the meanings when you use the computer to find the Jesus needle in the haystack

of words the French Catholic missionaries left behind. And yet, when you can

combine old-fashioned immersion with newfangled digitized searching,

revelations emerge -- as they did when we learned that the famous Cherokee newspaper the Cherokee Phoenix (published from 1828 to 1834) was digitized and available.

.

Finally, the Color of

Christ has souls that were born in the repetitive pains of new lives and

repeated deaths.

Finally, the Color of

Christ has souls that were born in the repetitive pains of new lives and

repeated deaths.

It is, on one hand, a narrative of Jesus born, murdered, and resurrected over and over and over and over. We wrestled with how people as individuals and communities live with such continual hope and sorrow. Even more, it is a book crafted in the emotional roller coaster of personal life and death. The research and writing of this book coincided with the birth, and then the sickness and death, of Elijah James Blum. The book became a refuge, a place where we could vest pieces of our vanishing relationships. When you read about the search for light, you unwittingly join Ed holding Elijah (who developed cataracts in his eyes from months 2 to 4) as he craned his head looking for the brightest light in the room. When you hear the accounts of Americans seeing Jesus emerge from pictures, you sit with Ed holding photographs of Elijah, knowing he won’t crawl out of them, but secretly hoping he would. When you encounter the idols smashed or the paintings torn, you witness Ed shouting prayers of four-letter words into the sky. And when you get to the epilogue about “Jesus Jokes,” you may see that hilarity can hide as much as it reveals. Laughter may not be a refuge from terror; the comedy may be its signal. Dad did his best, Elijah, to convey what you taught in the art form he knows best. Mom, Dad, and Uncle Paul miss you.

Edward J. Blum and Paul Harvey

We are grateful to the AAR, and especially to the North American Religions Section, the Afro-American Religious History Group, for convening the “authors meet critics” session. Our thanks, as well, to eminent scholars Stephen Prothero, Jennifer Graber, J. Cameron Carter, Kathryn Gin Lum, and Joshua Paddison, for giving their time and insights.

We are grateful to the AAR, and especially to the North American Religions Section, the Afro-American Religious History Group, for convening the “authors meet critics” session. Our thanks, as well, to eminent scholars Stephen Prothero, Jennifer Graber, J. Cameron Carter, Kathryn Gin Lum, and Joshua Paddison, for giving their time and insights.

Jesus Christ has had quite a decade. Millions watched him

brutalized in Passion of the Christ.

They shuddered (or celebrated) when Reverend Jeremiah Wright proclaimed that Jesus

was a “poor black man who lived in a country and who lived in a culture that

was controlled by rich white people.” More recently, Fox News anchor Megyn

Kelly mentioned that the duo of Jesus and Santa Claus were “white” men (then later suggesting that the issue was not settled), and the film "Son of God" gave us the viral hashtag #hotjesus.

For scholars, J.C. has had quite a ride too. Stephen

Prothero and Richard

Wightman Fox built upon the insights of Jaroslav

Pelikan, Kelly

Brown Douglas, and David

Morgan to detail the various ways he has factored in American history. With

The Color of Christ, the book’s website, and dozens of op-eds,

interviews,

and talks, we

threw our ideas into the mix. A paperback

edition will be released this summer for fall classes (if you teach the

book, please feel free to ask about a Skype session; we’re happy to oblige).

Scholarship and argumentation in academic fields tends to be

driven by “either . . . or” propositions: this

is right; that isn’t. The Color of Christ is a “both, and … and”

book. Maybe this is Ed’s way of rejecting his childhood of “neither, nor”

restrictions (we could neither drink orange juice after 9 am, nor purchase

anything without a coupon); or Paul’s way of rejecting too many sermons which

dwelt in the land of “neither . . . nor.” Below, we briefly spell out why we

brought together constructs that are sometimes separated, and attempted to

write a book that opened up possibilities and suggested new kinds of dialogue.

1. Jesus

and Christ

In American Jesus

and during the AAR conversation, Professor Prothero emphasized the distinction

he makes between Jesus and Christ. This, of course, is a crucial for history

and theology. Jesus is the historical person who lived millennia ago. Christ is

the theological signifier.

Our emphasis on both was not intended to hide those

differences, but rather to emphasize that the combination “Jesus Christ” plays

a powerful role in race making and hierarchy sustaining. As representations of

sacred flesh, visual images of Jesus and ideas of his body elevated

considerations of the physical to the planes of the supernatural. This is one

of our key points: American racial categories have been made, remade, and

endured, in part, because they have lodged themselves in considerations of the

human and other-than-human supernatural figure of Jesus Christ. The body

(Jesus) and the transcendent (Christ) were fused in an American society that

labeled bodies, legislated bodies, commodified bodies, separated bodies,

altered bodies, advertised bodies, and, through it all, crafted hierarchies of

bodies. Jesus Christ, as human and sacred, has been part and parcel of those

storylines.

2. Digital

and Material

We were trained before the explosion of digitized sources.

We slogged to out-of-the-way archives to locate sources (that may or may not be

there, regardless of what the finding aid said). While Paul worked through

illegible church records from the public library of Oxford, Mississippi, or

Native American sources stored at the Newberry Library, Ed thumbed through

Bible Sunday School cards in Philadelphia and frontier almanacs in Kentucky.

Digitization, however, opened the field widely.

Books.google.com made it possible for us to track the “Publius Lentulus

letter.” Searches for “white Christ,” “white Jesus,” “white savior” turned up

sources and points we would have never encountered on our own. Who knew, for

instance, that even Frederick Jackson Turner mentioned the whiteness of Jesus

in the early twentieth century? No way we could have found that otherwise.

We think Color of Christ

benefits from the combination of “old-fashioned” archival work and the digital resources revolution still with us. Josh Paddison raises some excellent points, and caveats, about how what is or is not available may shape scholarship in ways that are invisible. And certainly, to cite one example, simply doing a keyword search for “Jesus” in the online version of the Jesuit Relations is awfully convenient, but unless you’ve spent

hard time reading and studying the volumes and come to know the personalities

and styles of the individual authors, you are likely to miss crucial parts of

the meanings when you use the computer to find the Jesus needle in the haystack

of words the French Catholic missionaries left behind. And yet, when you can

combine old-fashioned immersion with newfangled digitized searching,

revelations emerge -- as they did when we learned that the famous Cherokee newspaper the Cherokee Phoenix (published from 1828 to 1834) was digitized and available.

We think Color of Christ

benefits from the combination of “old-fashioned” archival work and the digital resources revolution still with us. Josh Paddison raises some excellent points, and caveats, about how what is or is not available may shape scholarship in ways that are invisible. And certainly, to cite one example, simply doing a keyword search for “Jesus” in the online version of the Jesuit Relations is awfully convenient, but unless you’ve spent

hard time reading and studying the volumes and come to know the personalities

and styles of the individual authors, you are likely to miss crucial parts of

the meanings when you use the computer to find the Jesus needle in the haystack

of words the French Catholic missionaries left behind. And yet, when you can

combine old-fashioned immersion with newfangled digitized searching,

revelations emerge -- as they did when we learned that the famous Cherokee newspaper the Cherokee Phoenix (published from 1828 to 1834) was digitized and available..

Moreover, the digital age compelled us to bring to the

foreground how sources are created, collected, produced, distributed, and

repackaged. We considered those flows at other moments in time, such as the

importance of railroads or filmmaking techniques. We also tried to historicize

the digital age, by including an entire chapter (“A Deity in the Digital Age”) on

its role in shaping contemporary depictions of Jesus Christ and race.

3. Here

and There: North and South, East and West, the United States and the World

Ed is from suburban New Jersey. Paul is from rural Oklahoma.

Ed studied in Michigan and Kentucky; Paul in central Oklahoma and then in the

San Francisco Bay Area. Ed has taught in Kentucky, Texas, New Jersey, and San

Diego; Paul has taught in California, Tennessee, Indiana, and Colorado. These

experiences led us to refuse any narrative that privileges one place, and we did

not want to replicate the old East-to-West frontier thesis of ages past (our

thanks to scholars like Joshua Paddison, Derek Chang, Laurie Maffly-Kipp, and

the folks at Religion in the American West blog for this). For this reason, The Color of Christ ranges all over the

map. There are various metropoles: New York City as an importing and exporting

hub and location of capital accumulation; southern California for its cultural

capital in the realm of mass media; and the Mississippi River as the highway

for imagery and artifacts in an earlier era.

One of the main points of the book is geographical

crossings. Indebted to Thomas Tweed’s work, we emphasized the real and

imaginative journeys people took across space and time. Some left the United

States to be with Jesus in Palestine. Others brought J.C. to America in their

sacred texts, visions, or experiences. The dynamics of movement and of

geographies were crucial to how individuals and communities related to Jesus.

It was not simply Americans bringing Jesus to America. He, in visual imagery,

in emotional relationships, in spiritual experiences, brought Americans to

Palestine, to China, and even to the heavens.

4. Scholars

and Students

We are often asked about the audience of the book. Both of

us are deeply committed to making our best ideas intelligible to thoughtful

undergraduate students. We not only want those students to be able to

understand the work, but also to wrestle with it, respond to it, and create

their own works.

We also hope The Color

of Christ will lead our colleagues to ask new questions and generate new

approaches in their fields. We hoped the book would energize the field of

critical race theory with attention to matters deemed religious and sacred. We

hoped it would push scholars of evangelicalism to take material culture and

bodies more seriously and not simply present humans as disembodied idea

machines (what Bruno Latour calls the “mind-in-a-vat” approach). We hoped that those

who study Catholicism would wrestle, as our colleagues Jennifer Hughes and

Tracy Leavelle do, with the complex indigenous responses to American

Catholicism.

Here are a few examples of how we hid sophisticated

scholarly ideas into analysis that students can understand (we hope). When we

discuss Phyllis Wheatley’s eulogy for George Whitefield where she had him speak

words that he (probably) never said and that the gospels do not record Jesus

saying, we were indebted to work on mimesis. We imagined Wheatley having a

Whitefield puppet on her hand, and the Whitefield puppet had a Jesus puppet on

his hand. “He longs for you,” this Jesus voiced with strings tethered to

Whitefield whose strings then flowed to Wheatley. Here we have an individual

named after a ship and the white family who purchased her, yet working such

innovative magic through poetry that we wonder how many more layers there are.

Or, when we discussed slave spirituals and their creative

renderings of Jesus as “master”, or as “tiny”, or as “friend” we thought of

“hidden transcripts.” When we thought about white Jesus imagery in interracial

churches, or the omnipresence of Head of

Christ, we were thinking about Foucault’s considerations of surveillance.

Finally, the entire book begins with absence and the work of non-present

signifiers. The face of Jesus was not there; the young women were dead.

Postmodernism’s obsession with absence drives the study, but we

did not write with their rhetorics or language games. Knowledgeable readers

will catch the gestures, but we avoided the jargon. While words and

phrases such “bio-power,” “alterity,” and “genealogy” serve as useful scholarly shorthand to enormously complex and fruitful discussions, they can

signal to some readers “this book is not for you” or “come back when you’ve

read more.” Most importantly, the barriers those words build (and we

acknowledge that they tear down other barriers), run against one of the main

points of The Color of Christ: non

elites with their own vernaculars and cultural creations have created some of

the most fascinating religious cultures in the United States.

5. Death

and Life

Finally, the Color of

Christ has souls that were born in the repetitive pains of new lives and

repeated deaths.

Finally, the Color of

Christ has souls that were born in the repetitive pains of new lives and

repeated deaths.It is, on one hand, a narrative of Jesus born, murdered, and resurrected over and over and over and over. We wrestled with how people as individuals and communities live with such continual hope and sorrow. Even more, it is a book crafted in the emotional roller coaster of personal life and death. The research and writing of this book coincided with the birth, and then the sickness and death, of Elijah James Blum. The book became a refuge, a place where we could vest pieces of our vanishing relationships. When you read about the search for light, you unwittingly join Ed holding Elijah (who developed cataracts in his eyes from months 2 to 4) as he craned his head looking for the brightest light in the room. When you hear the accounts of Americans seeing Jesus emerge from pictures, you sit with Ed holding photographs of Elijah, knowing he won’t crawl out of them, but secretly hoping he would. When you encounter the idols smashed or the paintings torn, you witness Ed shouting prayers of four-letter words into the sky. And when you get to the epilogue about “Jesus Jokes,” you may see that hilarity can hide as much as it reveals. Laughter may not be a refuge from terror; the comedy may be its signal. Dad did his best, Elijah, to convey what you taught in the art form he knows best. Mom, Dad, and Uncle Paul miss you.

Comments