The Color of Christ Meets a Cast of Critiques: Part III of Series from the 2013 AAR

Today we continue our series featuring responses and critiques to The Color of Christ, presented at the 2013 American Academy of Religion in Baltimore. Today's response comes from Joshua Paddison, author of the outstanding recent book American Heathens, which we have discussed at the blog previously. Josh has posted here previously on this subject, in our series "Asian Americans and the Color of Christ."

Religion, Race, and

Historiography: The Color of Christ

Joshua Paddison

I was

trained in a history department and so it’s from that background, rather than

from religious or cultural studies, that I approach Blum and Harvey’s The Color of Christ. Today I’m going to

try to step back and explain how The

Color of Christ represents, in my view, a convergence of various strands of

recent U.S. historiographical development. To me, one of the values of the book

is how it sits at the nexus of some of the leading historiographical trends of

the past 25 years. I will mention four main trends that I think the book reflects

and then end by discussing one new direction I see it pointing us toward.

First, and perhaps most apparent,

is the book’s invocation and interrogation of “whiteness.” In the 1990s

scholars first began a widespread deconstruction of whiteness, viewing it as an

imaginative category with, like “blackness,” its own history. As David Roediger

wrote in 1994, whiteness, “far from being natural and unchallengeable, is

highly conflicted, burdensome, and even inhuman.” Although aimed at exposing

and ultimately tearing down white supremacy, whiteness scholarship came under

fire for—along with studies of “masculinity”—directing yet more attention to

the histories of white men and for de-emphasizing, even masking power relations

and the structures of white dominance.

Writing as they do after the

playing out of these debates, Blum and Harvey draw on the insights of whiteness

studies while largely avoiding its pitfalls. Their chronicle of the rise of the

white and then specifically Nordic Jesus shows us how the parameters of

“whiteness” changed over time as well as Americans’ startlingly wide range of

deployments of Jesus’s supposed whiteness. They do spend a lot of time talking

about white men but are careful to connect cultural representations of the

white Jesus to underlying power struggles. White Jesus, we are told, sanctified

war, slavery, segregation, dispossession, imperialism, immigration restriction,

and economic exploitation. The authors also work from a post-whiteness model of

inclusion, giving numerous examples in every chapter of how people of color variously

embraced, contested, and transformed Jesus’s whiteness.

The second trend I see the book

reflecting is historians’ increasing focus on intersections of religion and

race in U.S. history. In this Blum and Harvey are joining scholars of all kinds

who have steadily expanded the horizons of “intersectionality,” a paradigm that

began about 25 years ago exploring mainly the co-constitutive natures of race

and gender. Perhaps due to 9/11 and its aftermath, the last decade has seen a

surge of studies extending the insights of intersectionality to race and

religion, categories scholars have increasingly understood to be inseparable

and volatile—our authors use the term “combustible.” Henry Goldschmidt,

Sylvester Johnson, Curtis Evans, Derek Chang, Tisa Wenger, David Silverman,

Rebecca Goetz, Blum and Harvey themselves in their prior works, and many others

we could name are of course part of this effort mapping America’s

religio-racial terrain.

I’m sure Blum and Harvey would

agree that these earlier monographs make a broad, synthetic work like The Color of Christ at all conceivable. And,

like much intersectionality scholarship (my own book American Heathens included), it seems to me that Blum and Harvey

are on firmer ground when discussing the arenas of popular, material, and

political culture than when delving into people’s own senses of self. We are

left wondering, for example, if African American Christian men and women used

their racial, religious, and gender identities together to understand

themselves and their social world, or did they deploy one at a time? As

feminist scholar Jennifer Nash has recently

asked intersectionality scholars, “What determines which identity is

foregrounded in a particular moment, or are [all components] always

simultaneously engaged?” I would ask Blum and Harvey the same question.

The third trend the book embodies

is U.S. historians’ increasing embrace of multi-racial studies. Less and less

often do we see histories of one particular racial group in isolation, or

simply in relation to dominant white culture. More and more often we are seeing

comparative histories that show interconnections and interrelations between

African Americans, Native Americans, Asian Americans, Latinos, and other

groups. If I may toot the horn of my own subfield, the American West, for a

moment, historians of the West paved the way in this, exploring the complex

racial cauldrons of places like California and Hawai’i. Despite the fact that

both Blum and Harvey are primarily historians of African Americans and the

South, they recognized that limiting the scope of The Color of Christ to just black and white—though a lot easier, no

doubt—would not have captured the complexity of Americans’ conversation about

Jesus and race. I can remember a time when the working title of this book was “Jesus

in Red, White, and Black,” and indeed

the Native American and African American material here is rich. Material on

groups not “red, white, or black” is clearly not as rich, as our authors have

been the first to acknowledge. I for one am glad that they cast a wider net,

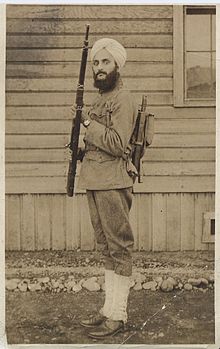

I’m glad that people like Bhagat Singh Thind and César Chávez make appearances

in the book, but their presence raises more questions about those groups’

perspectives than the authors answer.

The final trend I see the book

representing is the rise and mainstreaming of Mormon studies within U.S.

historiography. Probably due to a series of “Mormon moments”—the lifting of the

black priesthood ban in 1978, Mitt Romney’s Presidential campaigns of 2008 and

2012, the Church’s own “I Am a Mormon” campaign—we are in the midst of an

explosion of Mormon scholarship. For all the mentions of Mormonism in The Color of Christ, though, the authors

never quite explain why it was that

Mormons were, as they note, “some of the most powerfully committed to Jesus’s

(and their own) whiteness and strength.” Blum and Harvey make tantalizing

mention of an Army doctor’s 1858 report to Congress in which he described the

children of Mormon polygamy as a “new race” notable for their “yellow, sunken,

cadaverous visage; the greenish-colored eye; the thick protuberant lips, the

low forehead, the light yellowish hair, the lank, angular person.”

In fact, new scholarship is showing

how nineteenth-century Mormons were persistently racialized as less than fully

white. Mormons were especially viewed in terms of Orientalism, seen as

Orientalized facilitators of interracial mixing due to their religious and

sexual practices and absorption of various European immigrant groups. So

there’s a missed opportunity here where Blum and Harvey could have helped us

better understand the Mormon obsession with the white manly Jesus in the

context of their own precarious racial position. Also, a missed opportunity to

help us appreciate just how weird race

was in the nineteenth century. In fact, race was really, really weird, by today’s

standards, and that doesn’t quite come through.

I will conclude by discussing how I

see the book representing something quite new, and it’s in terms of its

methodology. If you look through the notes, you’ll see that The Color of Christ is largely based on

secondary sources but there are numerous moments where the authors dip into

primary sources of various kinds. The authors can correct me if I’m wrong but

my guess is that most of these were found online; I found 42 different websites

cited and that doesn’t include newspapers, books, and pamphlets the authors

likely found via Google Books and other digital repositories. I wonder how

different The Color of Christ would

have been if it had been written 20 years ago, in terms of access to digital primary

sources. Would they have been able to track something like the rise and fall of

the Publius Lentulus letter, one of the most fascinating threads in the book?

In this regard, The Color of Christ represents

an exciting research frontier that is shaping how all historians write.

The benefits of digitized sources

are plentiful. I wonder, though, if we aren’t seeing a simultaneous widening and narrowing of sources. To give one

example: Much of my research has focused on San Francisco. In the late

nineteenth century, there were six daily newspapers in San Francisco, but today

only three are available online—the Chronicle,

Call, and Alta California. I’ve

noticed a trend in new histories of San Francisco in which only these three papers

are consulted. I fear how the vicissitudes of digitalization projects and the

mysterious algorithms of Google’s search engine are warping our sense of the

past.

On a related note, The Color of Christ has an extensive website with hundreds of images, links to

primary sources, syllabi, interviews, and quite wonderful personal stories

contributed by readers. Born digital, the book is creating its own digital

footprint, and with its growing archive of readers’ stories, its own repository

of primary sources. As much as it represents recent trends in historiography,

as I’ve indicated here, its methodology, multi-formatted presentation, and cross-media

promotional campaign reflect our brave new digital world.

Comments