The Invention of American Evangelicalism; or, Why Ed Blum is Mad

(If you're unsure what made Ed mad read this post.)

[Update: Ed says he's not mad anymore, just passionate. Also, read this post from Ed where he expands his thoughts on race and evangelicalism. His thoughts echo much of what's in this post.]

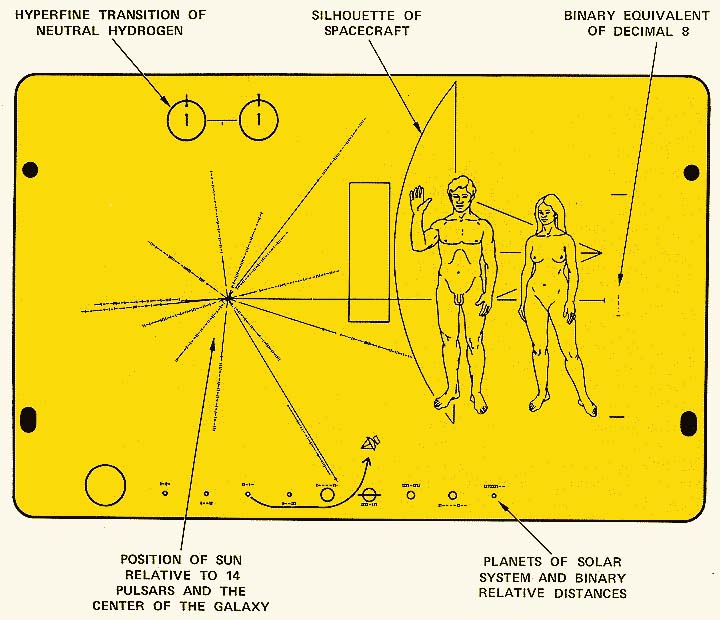

Evangelical history is a lot like this plaque from the Pioneer 10 and 11 spacecrafts. The plaque was affixed to the spacecrafts in order to communicate some basic information to any extraterrestrial life they might encounter as they zoomed toward Jupiter and beyond. The plaque is rife with information but the most obvious elements are the map of the solar system and the drawing of a man and woman. The plaque was meant to represent us (humans) to them (aliens). But more than that, the plaque also represents us to us. It shows what we thought was really important (hydrogen) and who we thought we were (that shapely white heterosexual couple with the man standing tall and waving while the woman extends her leg Angelina Jolie Oscars style). It represented us to ourselves.

This is the same dual work that much "evangelical history" does. On the one hand, the history of evangelicalism represents what evangelicalism is or has been to those not within the fold. It's a project that says, "See, we have been at the heart of democracy and republicanism in America. Ours is the religion of freedom, liberty, choice, and reason." It's also a project that represents itself to itself--that is, to evangelicals. Often these representations are meant to call today's evangelical Christians to be a better sort of Christians by reminding them of what they once were. "Once we had the social passion of the great abolitionists and the depth of thought of Edwards. We can have that again." I think it is this dual work of representation that creates the blindspots around race and gender that engendered Ed's battle cry and Kelly Baker's questions.

That said, I don't think the problem is really about representation. It's not that there aren't enough African American, Latino/a American, or Asian American evangelicals in our indexes and lists. The problem is not representation but construction. Or, to put it as a question, why do we think there even is such a thing as evangelicalism? Or evangelicals? To be blunt, why do we care who is or isn't an evangelical?

The term "evangelical" has a long history that I won't get into and that I'm sure many readers of this blog know more about than I do. However, it seems that the term has been self-applied or imposed upon a variety of Protestants since the Reformation. It is a "native term" batted about by Protestants throughout their various squabbles with themselves and others. For some American Protestants at certain places and times "evangelical" signified "true." Evangelical Christianity stood in contrast to infidel Christianity (be it liberal or deistic or what have you). Or conversely, to put myself in the shoes of the Unitarians I've been reading all week, "evangelical" Christianity is stiff mindless orthodoxy that lacks the refined reason and liberty of liberal Christianity. The question of who is or isn't "evangelical" or what is or isn't "evangelicalism" is a Protestant debate between Protestants and has become a historiographical question within American religious history insofar as American religious history is still under-girded by Protestant sensibilities and categories.

The real question for historians of American religion and especially historians of American evangelicalism is "what are the politics of the category evangelical?" Why do we want more African Americans in a list of evangelicals? Why do we want more women? Because it is a privileged category. It is also a constructed category. It is, to use my favorite Jon Butler phrase, an interpretive fiction. It is an invention, first within the minds of Protestants since the Reformation and then within the minds of historians from Robert Baird to the guys at Patheos. Rather than worry about who is or isn't an evangelical or adding more diversity to the list, historians should be investigating the process of this invention. We should be tracing the politics of the term and what is at stake in various places and times when people take, leave, fight for, argue about, or compromise over what it means to be "evangelical." We don't need more or different histories of evangelicalism or evangelicals, we need a genealogy of the term. We need to trace the invention of American evangelicalism. We need to stop assuming that evangelicalism is something out there for us to track down in the archive or research field and label correctly. Instead, let's pay attention to how various subjects imagine evangelicalism and the political, cultural, and social forces at work in those imaginings. Let's find out what's at stake when people get included or excluded from "evangelicalism." I'd do it but I have this other thing I'm working on.

Let me be clear, I don't think evangelical historians should stop doing what they are doing. The work of representing evangelical history to outsiders and other evangelicals is important and I'm glad there are wise and talented folks doing it. However, the ways these historian construct "evangelicals" is ripe for analysis by those investigating how "evangelicals" are invented. In this way "evangelical history" can be the source material for a genealogy of evangelicalism. For folks like Ed who are unsatisfied with our current constructions of "evangelical," adding a bunch of new names to the list or changing the category will not solve the problem. For a while "Puritan" stood as the privileged category of religious history. Perhaps we're now realizing that it's been replaced by "evangelical." (A process that itself is worth investigation). We have to deconstruct these categories and dig up the processes that have bestowed their privilege upon them, whether by historical subjects or historians. We can't just change the plaque on the spacecraft.

Comments

Although his book has a very different goal, your post reminds me somewhat of Darryl Hart's book Deconstructing Evangelicalism.

I think much of this impulse (both within American evangelicalism and within the historiography) grows out of the post-WWII moment at which self-consciously "evangelical" fundamentalists drew boundaries between themselves, fundamentalists, and liberal Protestants. If it was important to carefully demarcate groups of Protestants in the present, it was important to do so in the past. And perhaps if "evangelicalism" in the present was white, perhaps it was easy to only think about white "evangelicals" in the past. The prior generation of evangelical historians very much grew out of this post-WWII moment.

Like Ed notes, this is a battle not only within scholarship but with media perceptions of the term too. Why does news coverage of evangelicals seem to only cover white middle to upper class men? What do they gain by that construction of evangelical? To ask this more bluntly, what is the strategy and end game to this?

Moreover, why does it prove difficult to move away from such a rendering in public perceptions and also scholarship? For example in a well-known text on evangelicalism in the U.S., the author goes through great pains to say that the 1920s Klan is not evangelical nor fundamentalist but rather is pseudo-religious like, wait for it, the Nazis. This comparison of the Klan to the Nazis is already frustrating, but what the author misses is the Klan's Protestantism appears evangelical by standard definitions. Plus, the Klan was composed of white men (AND women), so members might fit easily into the representation that makes Ed so frustrated. But, they don't. This is crucial because it signals how the term evangelical is deployed as code for some white men, but the Klan is beyond that construction/representation. It seems that the construction and strategy that you mention also contains the politics of respectability.

Pasting message from Randall Stephens here from facebook:

Ed: I remember an essay that appeared in The Variety of American Evangelicalism that questioned the label "evangelical" for groups like the NBC, AME, and others. I think that might have something to do with this. If "evangelical" has a strong political dimension, then it doesn't work. It reminds me a little of something similar among pentecostals. If millennialism and esp premill is such a basic part of what it means to be pent, then how do we talk about the lack of premill focus in black pent churches?

Ed and KB, I'm glad you're picking up what I'm putting down. And, Kelly, I'll give you another example very different from the Klan. Right now I'm hammering away at a chapter that compares "evangelical" missionary descriptions of Hinduism with Unitarian descriptions from 1800-1830. These representations of Hinduism are tied up with the larger debates of the Unitarian controversy and revivalism/anti-revivalism. Usually we see the evangelicals on one side and the liberals on the other. But what about someone like Joseph Tuckerman? Or David Reed (editor of the Christian Register)? These two were interested in missionary work to India, hoped to see Hindus converted to Christianity, and argued that Unitarianism was a biblical theological position. That's 3 out of 4 Bebbington check boxes. I'm not saying we add Unitarians to the list. I'm saying the waters are murky and we must be aware of why we (or our subjects) choose the categories they do.

But I just want to add one cautionary note to all of this discussion. A lot of our discussing is slipping back and forth between commemoration and analysis with presumed communities. How do "we" define or analyze evangelicalism? Who do we "revere" in the history of evangelicalism? These are two VERY different projects that involve very different sets of interpretative apparatus and decisions. Both are also, I think, relevant to different communities--even if they at places overlap.

So perhaps we need to spend some time identifying the intended audience of this critique, because various points speak to various publics and there are points where they're uncomfortably conflated for me.

I didn't think Ed was suggesting that this is about representation and the noble title "evangelical" (which isn't really noble to many people). I thought Ed was referring to the way we arrived at the fact that some people are put on lists of movers-and-shakers in these powerful religious communities, and others are not. How did we get to the point that to be Rick Warren or Joel Osteen (and have evangelical empires of intellectual hegemony), you generally have to fit certain categories? And, how did we get to the point that we make lists of influential evangelicals?

It's not that we want more African Americans or women in a list of important evangelicals, but we want it to be recognized that this community reinforces many power relationships. That is, "families" are important, so those outside of heterosexual marriage relationships are less powerful. Men are understood as leaders, and those who don't identify as men are not likely to be understood as much as leaders. Articulate speech and a certain kind of showmanship is important. And, perhaps most glaringly of all, white people are understood as the default leaders.

Recognizing this within our scholarship and conversations about evangelicals is not just about giving credit where it is due (representation). Rather, it's about rethinking whether we want to reinforce these very power relationships by writing about the leaders in a community rather than those the leaders construct as the followers. Evangelicalism looks so different if you look at it from the bottom up.

I am loving a sneak peek of Ed and Paul's new book that I'm reading right now, mostly because it is the first comprehensive SOCIAL (bottom up) history of American Protestantism that I have ever read. And, it's very fitting, as I think of Paul and Ed as the leaders in the field I am in--of the social history of evangelicalism. So, as much as it's important for evangelicalism to have a history of its own, I think of Ed's work as a bottom-up history of religion in general...

Thanks for this, Mike. I spent my subway ride this morning hammering out thoughts similar to these on my phone, thinking I'd revise them and email them to Ed. But you've said much of what I wanted to say more quickly and more clearly than I did.

Part of what I was going to say was exactly your point about how it's not clear that we really should care who is or isn't an evangelical. Histories of evangelicalism often hinge on this question, with painful lists of definitions appearing in virtually every book introduction, all searching for some kind of objective standard by which to sweep people in or out. This always has looked to me like an exercise in futility (and, often, anachronism); the easier and more productive move is simply recognize that the term is inherently ambiguous. It always has been, and that ambiguity historically has been essential to how people have used it and understood the people whom it has marked. It's why journalists, historians, pollsters and of course putative evangelicals themselves often talk about evangelicalism in such varying ways.

I think that recognizing this allows us to address the points that John and Ed make in the comments. John brings up DG Hart's book because he finds the term really annoying and historically unhelpful--so much so that he recommends we abandon it. But Ed's point is that just shrugging our shoulders and saying that evangelicalism is useless overlooks the fact that the term has power. It means something for a lot of people, and it operates in the world in ways that matter. It makes lists like Time's possible. In a way, merely adding people to Time's list of 24 great white evangelicals merely perpetuates the term, its ambiguity, and the power that it allows people to wield. Of course, it's worth doing insofar as it redistributes the power that the category carries. But that kind of project also sanctions that power, in a way akin to the Native American use of the term "church" and the South Asian use of the term "Hindu" or even "religion."

So, I'm on board with the sort of genealogical project that you describe. That kind of project can highlight how and why people have come to understand evangelicalism and evangelicals in the ways that they have, and to what effect. Actually, this is the sort of conversation I tried to organize in 2008, with this series on over on the Immanent Frame. And it's what I'm trying to do now in my soon-to-be-completed (!) dissertation, which looks at the relationship between the evangelical book industry and the emergence of "evangelical" identity. It's admittedly mostly about white guys, but Ed's points, and yours, are near and dear.

Part of what I was going to say was exactly your point about how it's not clear that we really should care who is or isn't an evangelical. Histories of evangelicalism often hinge on this question, with painful lists of definitions appearing in virtually every book introduction, all searching for some kind of objective standard by which to sweep people in or out. This always has looked to me like an exercise in futility (and, often, anachronism); the easier and more productive move is simply recognize that the term is inherently ambiguous. It always has been, and that ambiguity historically has been essential to how people have used it and understood the people whom it has marked. It's why journalists, historians, pollsters and of course putative evangelicals themselves often talk about evangelicalism in such varying ways.

I think that recognizing this allows us to address the points that John and Ed make in the comments. John brings up DG Hart's book because he finds the term really annoying and historically unhelpful--so much so that he recommends we abandon it. But Ed's point is that just shrugging our shoulders and saying that evangelicalism is useless overlooks the fact that the term has power. It means something for a lot of people, and it operates in the world in ways that matter. It makes lists like Time's possible. In a way, merely adding people to Time's list of 24 great white evangelicals merely perpetuates the term, its ambiguity, and the power that it allows people to wield. Of course, it's worth doing insofar as it redistributes the power that the category carries. But that kind of project also sanctions that power, in a way akin to the Native American use of the term "church" and the South Asian use of the term "Hindu" or even "religion."

So, I'm on board with the sort of genealogical project that you describe. That kind of project can highlight how and why people have come to understand evangelicalism and evangelicals in the ways that they have, and to what effect. Actually, this is the sort of conversation I tried to organize in 2008, with a series on "Evangelicals and Evangelicalisms" (blogs.ssrc.org/tif/evangelicals-evangelicalisms/) over on the Immanent Frame. And it's what I'm trying to do now in my soon-to-be-completed (!) dissertation, which looks at the relationship between the evangelical book industry and the emergence of "evangelical" identity. It's admittedly mostly about white guys, but Ed's points, and yours, are near and dear.

To illustrate: In my nearly finished book on Joel Osteen and American Christianity I observe these power dynamics at play by examining the print and online publications of Osteen's critics-nearly all older white males who are intent on explaining why Osteen is not evangelical. Some (but not all) of these critics have long held a (perceived) place of power within American evangelicalism (here I know I’m assuming an operative definition), and thus assume in some measure that they are the gatekeepers of a specific, doctrinal definition of evangelical(ism). This episode in the book, I think, illustrates how gender and race and power are operative in the acts of erasing or including folks within the multiplicity of ways that both scholars and practitioners define evangelical(ism). Why is it that folks assume Osteen is a leading evangelical? And why are the vast majority of his critics white males in positions of power?

An interesting point here: both the New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture [vol 1] and Barry Hankins’ narrative history of evangelicalism have a photo of Lakewood’s congregation on the cover (in fact, variants of the same photo) yet neither book deals with Lakewood or Osteen. How is it that Lakewood/Osteen could in some measure represent “southern religion” or “evangelical” yet not be included in either text? Conversely, Joel’s father John Osteen, a leader in the neopentecostal movement, has an entry in Randall Balmer’s encyclopedia of evangelicalism. Please understand this is neither a critique nor attack on Samuel Hill or Barry Hankins (and it may have been a decision of their respective presses to include the photo anyway)—I respect and have benefitted tremendously from their work—but simply to illustrate the many issues this and recent posts surface.

Additional thoughts: John Turner, in his Patheos piece, mentions that Osteen should be included in a list of evangelicals, and I think many scholars would agree that Osteen is at least worthy of some scholarly attention for trying to understand this contemporary moment in American religion. But talking to many evangelicals over the last few years in my fieldwork, my impression is that many practitioners insist that Osteen is not evangelical. So, as Mike rightly notes along with Janine and others, there is always much at stake in these definitional disputes and acts of erasure and/or inclusion, especially as we view the Osteen story from both top-down and bottom up.

Phil Sinitiere

However, I also think that it is useful to remember that there is another way that the concept is used, which is to try to make sense of and explain complicated religious movements in history. For instance, it is important to try to explain dynamics of the First Great Awakening, why Baptists and Methodists grew so rapidly in the early 19th century, why some Congregationalists in 1890 identified themselves with Washington Gladden and others with Dwight Moody, why blacks formed Baptist and Methodist churches after the Civil War when other religious options were available to them, and a whole host of other questions. And what do these movements have in common with each other or with groups today? Some sort of religious phenomenon ties these things together and evangelicalism seems to be the best way to describe them. Yes, the term is messy and ambiguous and gets caught up in whiteness and poltiical gatekeeping. Welcome to religion in America.

But I should point out that the term can help us understand groups that did not necessarily describe themselves as evangelical. In this way, self-identity as an evangelical becomes less important.

And if we want to make it even more interesting, we could expand the discussion beyond the ever-powerful conceptual boundaries of the modern nation-state. Can the concept of evangelicalism help us understand the East African Revival, pentecostalism in Guatemala and house-churches in China? Few of the people in these movements would identify themselves as evangelical, but they all have what might be called evangelical characteristics. Our footing is even more slippery here, given the very obvious cultural differences we are dealing with, but I would hazard that it might be helpful insofar as it helps us see common religious forces driving these movements, even amidst the diversity. If you don't use "evangelical" to help describe what is held in common by George Whitefield, circuit-riding Methodists, Moodyite revivalists, black Baptist preachers, female holiness faith-healers, Ugandan itinerants, Guatemalan evangelists and Chinese leaders of Bible studies, is there another term that can be used? Or do they really have nothing in common? Or do the explantory categories run along different lines?

Jay R. Case

When we look at Whitfield and the colonial revivals, the rise of Methodists and Baptists, or even Moody, I fell much more comfortable talking about "revivalism" than "evangelicalism." I prefer revivalism because it tends to point us towards rhetorics, practices, bodies, places, and things and it lacks the identity politics of "evangelical."

Arlene Sanchez Walsh mentioned in a comment to Ed's "Blog Race War" post that evangelical studies is the study of middle-class men, and Kelly points out in her comment above that "new coverage of evangelicals seems to only cover white middle to upper class men," but that's the only notice that class has received in this discussion.

This isn't surprising. Class is regularly overlooked as a piece of the puzzle in the study of religion in America (as both Bob Orsi and Sean McCloud have pointed out so well). But I think that Ed's excellent point about "whiteness studies" and Laurie and Kelly's about gender needs to be extended to class as well. That TD Jakes picture doesn't only slam race and gender in your face (illuminating what is ordinarily "hidden in plain sight," to use Ed's words, when you start looking for these things); class is right there, too, in his style and his celebrity (which is selling the product that the image is advertising).

Class is at work in so many complicated ways, no less than race and gender. Let's not leave it out.

One another point, Mike pointed to the utility of revivalism vs. evangelicalism in the nineteenth century. I think this is a very interesting point, but I also think his mention of Moody complicates the issue. What do we do with people like Moody? Moody was very revivalistic, and many would classify him as evangelical certainly. Yet, Moody also appears to be very self-consciously trying to craft a persona that appealed to a variety of people. In other words, he--from what I understand--believed in biblical inerrancy and dispensational premillennialism, but avoided these controversies in his revivals to appeal to large audiences. Would he be evangelical, fundamentalist (or at least proto-fundamentalist I guess for his time), or would revivalist be a better term? But if we simply name him revivalist do we--like his audiences perhaps--fall into the trap of letting him define himself and his persona instead of questioning what is going on behind this persona? (Thinking about Moody for my next project which is why I bring it up)

But I think Moody is interesting to juxtapose to Joel Osteen and the question of whether or not he is evangelical (and I'm looking forward to Phil's book). Who gets to decide this? Is Phil to make that decision--if so, where do you finally come down on this? Should we let someone like Rick Warren claim he is not evangelical because Warren does not like Osteen's prosperity theology? Should we go with Osteen's own definition--who may (for all I know) not classify himself as an evangelical which itself seems like a very evangelical thing to do?

I think we have a very interesting scholarly onion here, friends. It should keep us busy until the next generations picks us apart for the things we aren't questioning :-)