What's at Stake? Race and Evangelical Naming

Edward J. Blum

(update: for more perspective, see Kelly Baker's take)

By drawing attention to the Time list of "influential" evangelicals and John Turner's essay, I'm not trying to say that evangelical scholarship is racist. I'm also not trying to say that African Americans should want to be identified as "evangelical" or necessarily included in that camp. I'm also not saying that we all need to have "additive" history where we merely add a person of color or a woman to make our stories better (would adding women to Kevin Schultz's book improve it? I'm not so sure).

What I am saying is that when it comes to "evangelicalism" and race, we cannot divorce the work that race did. My first book was based on a simple and perhaps naive graduate student question: when Dwight Moody set the North ablaze with the revivals of 1876 and 1877, why didn't he have anything to say about racial justice in the South? Why didn't Marsden or Noll or hardly else bring up that these were years of terrible racial and sectional strife? (Noll is the great example of a scholar who has grown so richly over time and now takes race quite seriously; but he did not in Scandal!) That led me to an unbelievable discord of rhetoric versus reality in post-Civil War evangelicalism that showed how folks like Moody subtly created a white supremacist morality that undermined the gains and spirit of radical Reconstruction. But this "evangelical" history rarely gets told.

American evangelicalism cannot be separated from race and gender power relations and identities. When southern white evangelicals wrote their treatises on the "spirituality of the church," they did so not only as black men and black women labored so white ministers had pen and paper (and their readers had time), but also on the very ground that Native Americans had once claimed. These evangelicals wrote as women of various hues tended to their physical and material needs. To leave those histories out, to lionize men who have had every advantage in the world, is to miss something so deep and so real: that their wealth of ideas, of reflection, of money, and of influence, was built upon the labors, the procreation, the removals, the sorrow songs, the frustrations, of others. Do we want to be like Perry Miller, talking about "errand boys" figuratively while literal "errand boys" wait upon the whites around us? That strikes me not just as bad history, but also as the kind of history that hides realities of power. I want to write history that speaks truth to power.

And this is what drove my book with Paul on Jesus and whiteness throughout American history. While at some times whites did talk about Christ's white image around them, most of the time his whiteness went unstated. It was assumed, meant to creep into the hearts and minds of those who viewed it, especially children. Whiteness created a morality before moral questions could be addressed, it became a psychological certainty before other theological uncertainties could be dealt with. If we never called out the whiteness of those Jesus images, then we would not have seen a large part of what they represented: group dominance in various forms. Thank God for those who did speak up.

To have an America that moves beyond segregation religiously, then we need to have the historical imagination to move beyond it as well. Ida B. Wells did not influence her generation to end lynching. But isn't it her faith legacy we want to remember more than Thomas Dixon's? When we remember Charles Finney's new measures, should we not also remember Samsom Occum and William Apess and David Walker who created the notion of religious hypocrisy as a greater injustice than violating white supremacist laws? In part, this is to create a usable history. But also, it's to create a religious history of the United States that puts power in its place, recognizes whiteness and male power even when it is unspoken but exerted, and that accomplishes what scholars are called upon to do: reveal that which is cloaked.

(update: for more perspective, see Kelly Baker's take)

By drawing attention to the Time list of "influential" evangelicals and John Turner's essay, I'm not trying to say that evangelical scholarship is racist. I'm also not trying to say that African Americans should want to be identified as "evangelical" or necessarily included in that camp. I'm also not saying that we all need to have "additive" history where we merely add a person of color or a woman to make our stories better (would adding women to Kevin Schultz's book improve it? I'm not so sure).

What I am saying is that when it comes to "evangelicalism" and race, we cannot divorce the work that race did. My first book was based on a simple and perhaps naive graduate student question: when Dwight Moody set the North ablaze with the revivals of 1876 and 1877, why didn't he have anything to say about racial justice in the South? Why didn't Marsden or Noll or hardly else bring up that these were years of terrible racial and sectional strife? (Noll is the great example of a scholar who has grown so richly over time and now takes race quite seriously; but he did not in Scandal!) That led me to an unbelievable discord of rhetoric versus reality in post-Civil War evangelicalism that showed how folks like Moody subtly created a white supremacist morality that undermined the gains and spirit of radical Reconstruction. But this "evangelical" history rarely gets told.

American evangelicalism cannot be separated from race and gender power relations and identities. When southern white evangelicals wrote their treatises on the "spirituality of the church," they did so not only as black men and black women labored so white ministers had pen and paper (and their readers had time), but also on the very ground that Native Americans had once claimed. These evangelicals wrote as women of various hues tended to their physical and material needs. To leave those histories out, to lionize men who have had every advantage in the world, is to miss something so deep and so real: that their wealth of ideas, of reflection, of money, and of influence, was built upon the labors, the procreation, the removals, the sorrow songs, the frustrations, of others. Do we want to be like Perry Miller, talking about "errand boys" figuratively while literal "errand boys" wait upon the whites around us? That strikes me not just as bad history, but also as the kind of history that hides realities of power. I want to write history that speaks truth to power.

|

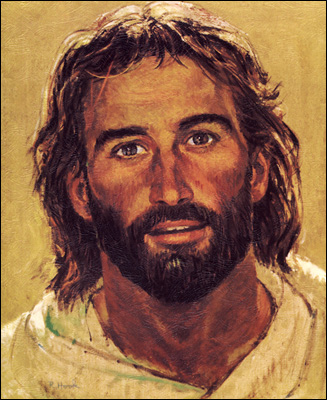

| Richard Hook, Head of Christ (1964) |

And this is what drove my book with Paul on Jesus and whiteness throughout American history. While at some times whites did talk about Christ's white image around them, most of the time his whiteness went unstated. It was assumed, meant to creep into the hearts and minds of those who viewed it, especially children. Whiteness created a morality before moral questions could be addressed, it became a psychological certainty before other theological uncertainties could be dealt with. If we never called out the whiteness of those Jesus images, then we would not have seen a large part of what they represented: group dominance in various forms. Thank God for those who did speak up.

To have an America that moves beyond segregation religiously, then we need to have the historical imagination to move beyond it as well. Ida B. Wells did not influence her generation to end lynching. But isn't it her faith legacy we want to remember more than Thomas Dixon's? When we remember Charles Finney's new measures, should we not also remember Samsom Occum and William Apess and David Walker who created the notion of religious hypocrisy as a greater injustice than violating white supremacist laws? In part, this is to create a usable history. But also, it's to create a religious history of the United States that puts power in its place, recognizes whiteness and male power even when it is unspoken but exerted, and that accomplishes what scholars are called upon to do: reveal that which is cloaked.

Comments

Also, certain "Evangelicals" whose faith was expressed in the ending of white suprermacy are presented as "Abolitionists" or placed in the "fanitic" category. I am thinking of the article I am working on John Brown whose motive can only be comprehended as due to his reading of and belief in the bible. Brown, however, is never listed as an Evangelical in typical Anerican Religious History texts because of the sub-conscious racial taxonomy. So too, figures such as Nat Turner, Sojourner Truth, Harriett Tubman are not mentioned in discussions of "Christian Spirituality." The racial taxonomy evident in so much "scholarship" renders all human subjects one-dimensional.