5 Questions with David Endres

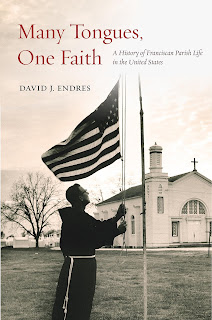

I corresponded recently with Fr. David Endres about his new book, Many Tonges, One Faith: A History of Franciscan Parish Life in the United States. Fr. Endres is Associate Professor of Church History and Historical Theology at the Athenaeum of Ohio where he also serves as Dean. He is also the hardworking editor of the US Catholic Historian.

I corresponded recently with Fr. David Endres about his new book, Many Tonges, One Faith: A History of Franciscan Parish Life in the United States. Fr. Endres is Associate Professor of Church History and Historical Theology at the Athenaeum of Ohio where he also serves as Dean. He is also the hardworking editor of the US Catholic Historian.(1) Writing a history of Franciscan parishes is a huge undertaking. As you note, at the height Franciscan parish ministry in 1968, the order ran around 500 parishes and missions in the US. Tell the blog how you approached this challenge and why you settled on writing the history of fourteen specific parishes.

Unlike the Jesuits and Dominicans, among other religious communities, there have been almost no studies of US Franciscanism to date. That was the impetus for the United States Franciscan History Project under the direction of Jeffrey Burns and the Academy of American Franciscan History: to bring together scholars to reflect on different aspects of the US Franciscan story. In addition to my book on Franciscan parishes, there has been one other monograph published in the project series: Ray Haberski’s Voice of Empathy: A History of Franciscan Media in the United States. Hopefully, additional forthcoming volumes will address other topics.

One 1950s survey of the Franciscans’ US presence blamed factionalization within the Franciscans on the lack of national or international studies that go beyond a given Franciscan province or branch of the order. He (a friar himself) lamented that he would never be able to please his confreres -- the Conventuals, Third Order Regular, and Capuchins would feel overlooked if he concentrated on the more numerous OFMs (Friars Minor) and all the priests and brothers would resent being chronicled along with the secular Franciscans and the numerous women’s branches.

I tried to keep some balance, and perhaps since I am not a Franciscan myself, I was a bit freer to shape the book around specific parishes – no matter the branch or branches of Franciscanism represented. I looked for compelling stories that related to broader developments in the history of the Church and nation, but also attempted to provide a diverse representation of parishes – ethnically and geographically, large and small, active and now closed or merged. I knew that to tell such a large story, I had to be selective in choosing parishes to detail. The number “fourteen” was somewhat arbitrary, but I think it provides enough case studies to derive some general conclusions.

To achieve this diversity of place and kind, I made use of numerous archives. The archives of the St. Barbara Province in Santa Barbara, California and the St. John Baptist Province here in Cincinnati provided a wealth of information. Even though Cincinnati is 800 miles from New Orleans, friars from the Cincinnati province ministered in Louisiana (along with Michigan, Indiana, Kentucky, Arizona, and New Mexico) so archives helped extend my research reach. Other holdings were consulted in person or with the help of kind archivists and librarians.

(2) You show how Franciscans very much became tied to place in America. Tell the blog how the order was shaped by American realities.

I think that too often scholars (who do not necessarily focus on religious history), see Catholic history in particular as not having much to do with the US historical narrative. But in addition to being tied into major developments in American Catholic history, the book, I hope, helps explore major demographic and social trends that transcend the US Catholic experience.

Those developments included the realities of frontier life, massive European immigration, and the emergence of ethnic-predominate cities. These geo-demographic shifts propelled Franciscans into pastoring parishes in the nineteenth century, though this was not part of their experience in Europe.

In the latter half of the twentieth century, the Franciscans were again shaped by new American realities – the interstate highway system, growth of suburbia, the Baby Boom, feminism, and protest movements of the 1960s and beyond. All of these impacted parish life, affecting how Franciscans ministered and how they assessed their ministries.

By engaging some of these broader developments in American life and the American religious experience, I hoped to situate Franciscan parishes within the US historical narrative, not as an aberration, but as a nexus of local institutions and communities that help compose the “American story.”

(3) Many Tongues, One Faith is as much a global story as it is a national story. How does the story of the Franciscans compare to other orders? I'm thinking here of John McGreevy’s work on the Jesuits. Both orders were shaped by the secularization policies of Europe and their coming to the US, but did they respond in different ways?

It is certainly a global story. The first Franciscans to the US – whether Irish, Italian, German, or Polish – all came from European provinces, bringing with them their own ideals and expectations about being Catholic, being Franciscan, and being ministers of the Gospel. This was not unique to the Franciscans, but I think that friars and religious sisters responded in different ways from the Jesuits and others, partly because of the distinctiveness of their charism.

In the conclusion of the book, I discuss the Franciscan charism: to be poor among the poor; to foster fraternity and community; to be ministers of reconciliation, healing, and peace; and to serve where there is the greatest need, often among those on the margins of society. Their charism, especially the commitment to ministering to the underserved, impacted the locus of their ministries. While the Jesuits had a lively Euro-American exchange of personnel among their colleges, the Franciscans were missioned to the frontier, or urban centers, or Native American missions. Though some returned home later in life, most stayed in America. Consequently, their lives were significantly shaped by their local experiences of ministry and the people they encountered. More so perhaps than other orders, the Franciscans seemed to stay close to the people, identifying with them, no matter if their own ethnic, racial, or socioeconomic backgrounds were dissimilar.

The work of John McGreevy and others now provide some interesting possibilities for inter-“religious order” comparisons. The Jesuits, more so than the Franciscans, traveled to and from Europe – even after many years of ministry in America – and maintained a close connection to the Jesuit superior general in Rome. The order overall maintained a greater top-down, military model. Overall, my reading of the Franciscan story is that they were more decentralized in their identities and decision-making. The provinces and the semi-autonomous Franciscan “custodies” emphasized local governance. This helped them to respond to local situations and needs in ways different from other orders.

(4) Of the fourteen parishes you wrote about, do you have a favorite?

Of those that I detail in the book, the one that has resonated most with me is the Shrine of Our Lady of Consolation in Carey, Ohio, located about three hours north of my home. As a Marian shrine that remains popular among pilgrims, it is a place where the present is linked to the past. In Carey, an image of Our Lady of Consolation was imported from Luxembourg and brought in procession to its new home at the church in 1875. On the day of the procession, rain threatened on all sides but did not fall on the statue or procession. The safe passage of the statue through the storm was viewed as miraculous. At the same time, unbeknownst to those in the procession, a little girl whose family had taken part in the procession was healed from an incurable illness. It was the first of many miraculous healings, which many believe continue at the shrine today. Dozens of artifacts lining the shrine’s walls stand as testimony to the claims: crutches, casts, splints, and even a six-foot-long wicker basket.

The history of the shrine is full of fascinating stories – some of which are outside the scope of Many Tongues, One Faith or could only be discussed briefly therein. I am particularly interested in the healings said to have occurred there and how they were publicized, especially in the first decades of the twentieth century. The healings shed light on ethnic and devotional Catholicism and how “holy places” operated within the psyche of American Catholics. And as much as believers venerated the location as a place of special intercession by the Blessed Virgin Mary, the shrine also has been the target of anti-Catholicism: a Ku Klux Klan demonstration, an arson attempt, and a successful theft of the famous statue. The vacillations of belief and doubt provide an interesting lens to view religious devotion, reported miracles, and the advancement of science.

My study of the shrine has developed into a near book-length manuscript, “America’s Lourdes: Devotion and Healing at the Shrine of Our Lady of Consolation.” I hope to further develop the topic over the coming years and ready it for publication.

(5) Your book builds on the social history tradition of Jay Dolan and Patrick Carey’s classic studies of parish life. One might say the parish is where “the rubber meets the road.” Why is the parish still a great lens to use to study US Catholic history?

I am indebted to earlier scholarship that helped focus on lay Catholics and their involvement in parish life. Today, as in the past, most Catholics’ experience of the Church is at the level of the parish. More so than any diocesan structure or specialized Church-run institution, the parish is primary to a community’s religious experience. The correspondence of bishops, their sermons, and financial ledgers readily available at diocesan archives tell part of the story, but only part of it. Getting beyond institutional records to tell the stories of communities is the challenge and also the benefit of researching parishes.

I attempted to use various sources to find the “voice” of friars, women religious, and lay Catholics, utilizing local and parish histories, newspapers, bulletins, and occasionally, interviews. My hope is that it has helped flesh out the lived experience of everyday “people in the pews.” Of course, a selective, case-study approach offers some insights into that experience, but also implicitly points to the need for further studies. If my research has provided an impetus or avenues for future research, it will have achieved part of the goal of the United States Franciscan History Project.

Comments