Do Catholic Historians Need to Define Catholicism?

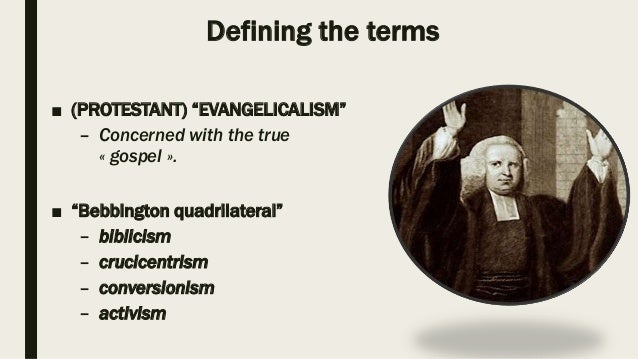

Historians of evangelicalism are very interested in defining evangelicalism. It would seem obvious that scholars of a certain field would be dedicated to defining their object of study, but historians of evangelicalism go about this task with an admirable gusto. The act of defining is central to the field. Historian David Bebbington’s famous definition, the Bebbington Quadrilateral – evangelicalism as biblicism, crucicentrism, conversionism, and activism – has framed the conversation since 1989. As I listened to the excellent papers delivered by historians at the Noll Conference in March 2018, I began to wonder why Catholic historians do not seem so interested in defining their object of study, Catholicism.

Historians of evangelicalism are very interested in defining evangelicalism. It would seem obvious that scholars of a certain field would be dedicated to defining their object of study, but historians of evangelicalism go about this task with an admirable gusto. The act of defining is central to the field. Historian David Bebbington’s famous definition, the Bebbington Quadrilateral – evangelicalism as biblicism, crucicentrism, conversionism, and activism – has framed the conversation since 1989. As I listened to the excellent papers delivered by historians at the Noll Conference in March 2018, I began to wonder why Catholic historians do not seem so interested in defining their object of study, Catholicism.Certainly we do not have quadrilateral. But should we have one?

Two answers to the question about the lack of enthusiasm for defining Catholicism pop up immediately. First, Catholicism does not appear to be as controversial in American politics, and as a result, the stakes of defining it are not as high. The conference suggested there is a pressing need to define evangelicalism in order to understand present day voting patterns. The second factor easing any pressure to define Catholicism is the structure of the Church itself. The centralized nature of the Church relieves scholars of the need to define Catholicism. At the conference I asked two colleagues who study evangelicalism why historians of Catholicism are not interested in definitions. Basically, the response I received was that the structure of the Catholic Church – a Pope and a hierarchy – means that less is up for grabs.

We should pause to ask if having a debate about the definition of Catholicism would be productive. I imagine some will think that having such a conversation would only serve as a distraction. But I found the debate about evangelicalism at the Noll Conference to be fascinating and generative. Is it a theology? Is it a politics? Is evangelicalism the media you consume? Is it a set of ideas? Is it worship? Is everyone who likes Billy Graham an evangelical? Is the scandal of the evangelical mind still scandalous?

It is possible to conclude that Catholic historians have been debating the definition of Catholicism implicitly in their books for years. The closest our field comes to The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind might be William Halsey’s classic study, The Survival of American Innocence: Catholicism in an Era of Disillusionment, 1920-1940. Halsey argued that a neo-scholastic worldview allowed Catholics to imagine themselves as existing outside the tragedy of twentieth century American history (the rise of ethical relativism, psychoanalysis, and subjectivity). It is tragic in Halsey’s tale, and rather a scandal, because the static mentality of Catholicism made it obtuse. Other scholars followed his lead and defined Catholicism as static because of the intellectual freeze brought on by the condemnations of Americanism and Modernism. But Halsey makes the important point that Catholicism could be construed as a set of mental categories. He does define his object of study. Jay Dolan’s work implied that only the methods of social history could move scholars of Catholicism closer to a useful definition of what they study. John McGreevy’s Catholicism and American Freedom would say Catholicism is an assent to a set of ideas. His Parish Boundaries would locate institutionalism at the center of what it means to be Catholic. His latest work on the Jesuits suggests any definition of Catholicism must consider the global. Robert Orsi’s work defines Catholicism as a religion of practice replete with longings for connections to the “real presence.” Relationships between heaven and earth are also at the heart this Catholic identity. As is gender, as works by Amy Koehlinger, Kathleen Sprows-Cummings, and Mary J. Henold make clear. The essays in Habits of Devotion on confession (James O’Toole), the Eucharist (Margaret McGuiness), prayer (Joseph Chinnici), and Marian devotion (Paul Kane) identify Catholicism as profoundly ritualistic and sacramental. Peter D’Agostino argues that Rome and trans-nationalism are key to defining American Catholicism. Younger scholars are contributing to this debate and taking it in new directions. Matthew Cressler has raised the question of how the definition of American Catholicism changes when we locate black Catholics at the center of our story. Catherine Osbourne’s new book suggests professionalism and professional identities are important to Catholic life in the twentieth century. Jack Downey makes the point that Americanization of Catholicism and its entrance into mainstream of American life should not stand as the ultimate end point for defining the men and women of the Old Faith. Not all Catholics wanted mainstream status because such an “achievement” entailed an ensnarement in modern materialism.

Catholic historians debate definitions of Catholicism without a central framing device.

This blog post raises the question of whether Catholic historians need a device like a quadrilateral to shape this debate and give it some structure. The question assumes, perhaps incorrectly, that scholars can, in fact, define Catholicism. It also pushes past any reservations about debating a definition rather than figuring out how Catholics shaped American History. But what if we synthesized the works in the field to produce a four-pronged definition? What would rise to the surface if we made it goal to boil it all down to four categories? Or could we define Catholicism with a broader categorical move? Is it a theology? Is it a set of institutions? Is it an imagination? We might return to some classic sources written by theologians and social scientists. David Tracy’s Analogical Imagination or Andrew Greely’s The Catholic Imagination both spring to mind. Historians might walk the path hewn by the editors of the recently published The Anthropology of Catholicism: A Reader. Scholar of religion Kate Dugan, in her useful review, teases out the questions asked across the volume’s essays: “What counts as a Catholic idea and a Catholic person? Why does Catholicism continue to have influence the twenty-first century? If there is a Catholic imagination, or Catholic imaginations, who acts in it?” Historians of Catholicism might follow the lead of evangelical historians and these anthropologists and then ask a pack of similar questions. Then, of course, we should deliver a satisfying answer.

Comments