Introducing America's Public Bible (Beta)

It’s the start of August, and I don’t want to presume on the good graces of this blog’s readers. So in the spirit of late summer, I’m finally getting around to briefly describing of one of my summer projects in the hope that you find it fun, leaving a fuller accounting of the why and wherefore of the project for another time.

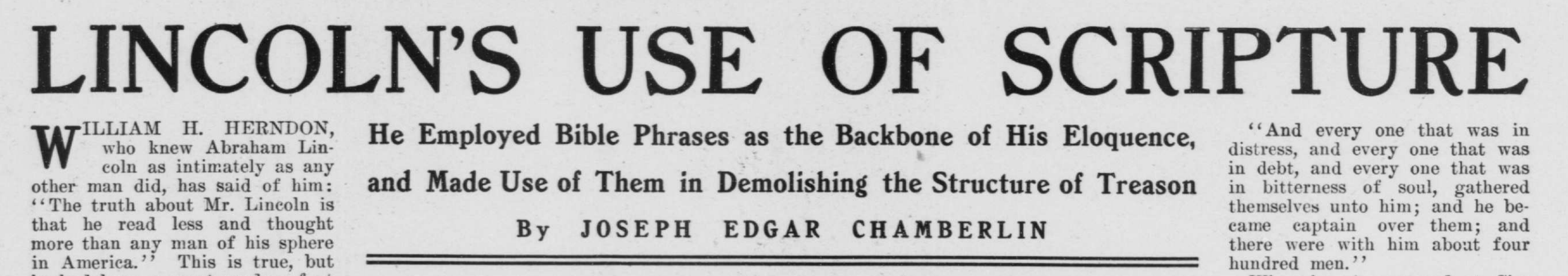

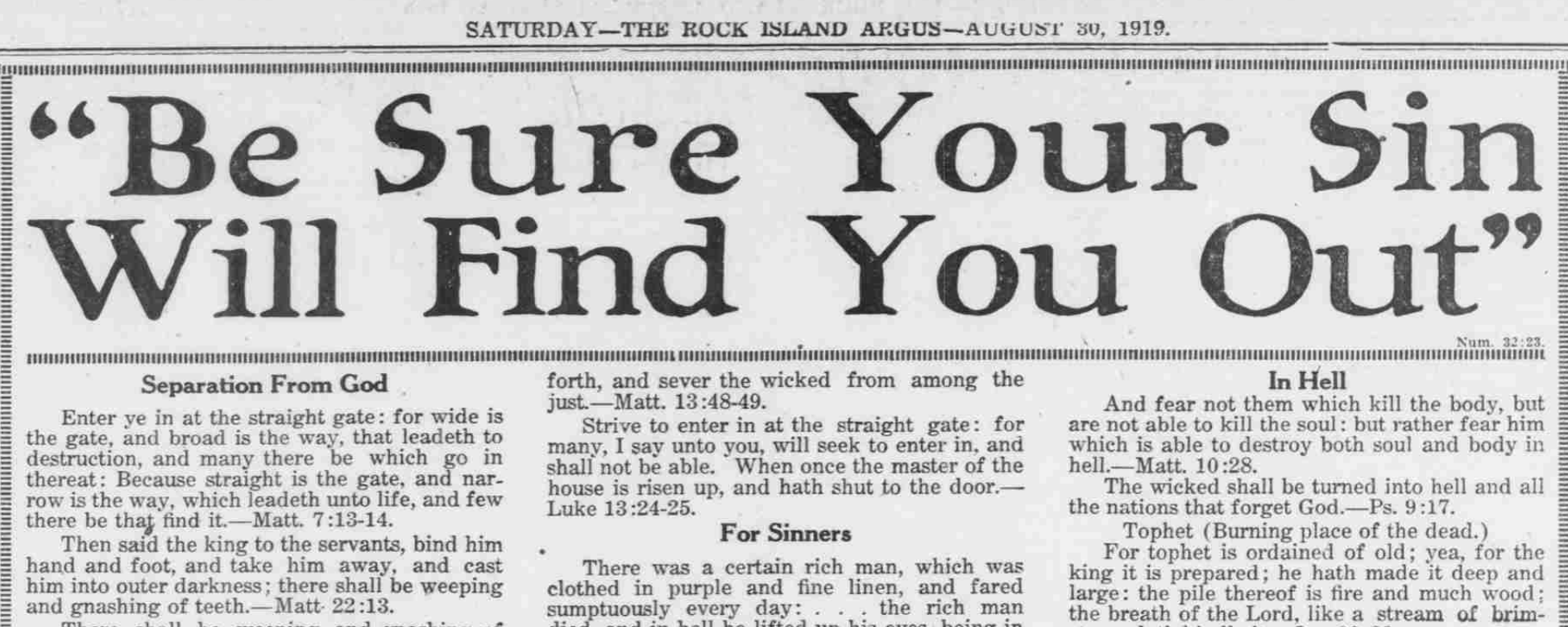

America’s Public Bible is a website which looks for all of the biblical quotations in Chronicling America. Chronicling America is a collection of digitized newspapers from the Library of Congress as part of the NEH’s National Digital Newspaper Program. ChronAm currently has some eleven million newspaper pages, spanning the years 1836 to 1922. Using the text that ChronAm provides, I have looked for which Bible verses (just from the KJV for now) are quoted or alluded to on every page. If you want an explanation of why I think this is an interesting scholarly question, there is an introductory essay at the site.

The project offers you two ways of exploring how the Bible was used in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century newspapers. First, you can use an interactive chart, which lets you put in the reference to any of the 1,700 or so most quoted Bible verses and see the changing patterns in their usage. For example, you might find that “Righteousness exalteth a nation: but sin is a reproach to any people” (Proverbs 14:34) peaked in 1865, that “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends” (John 15:13) grew in popularity during World War I, or that “Suffer little children to come unto me” (and its variations) was the most popular verse in this collection of newspapers. You can also see the trends for collections of verses arranged in topics that I’ve chosen from you, if your knowledge of biblical references is rusty.

The second way that you can use the site is to get links back to the images of the newspaper pages at Chronicling America with the quotations highlighted. This lets you seen not only how often and when a verse was used, but by whom, in what contexts, and for what purposes.

I’ve had an enormous amount of fun working on this project, and I hope you will enjoy exploring this initial version of the site. Part of the fun was figuring out how to find the quotations using machine learning, though I acknowledge that my definition of “fun” might not exactly line up with everyone else’s. But the real pleasure came in poring over thousands of instances of how the Bible was quoted. Peter Stallybrass has a gem of an article called “Against Thinking” where he encourages literary scholars to build up an inventory of things that they have noticed about a text. (Seriously, go read that article; I can’t do it justice here.) Making all due allowances for the differences between disciplines, this is exactly what I found myself doing as I cataloged how the Bible was used to discuss politics and elections, money and capitalism, gender roles, and science, as well as (to my surprise) to make lots and lots of jokes.

Of course, that catalog will eventually have to amount to an argument, about which more in the future. But in the meantime, I hope you have fun looking up examples of how the Bible was used in American newspapers.

Comments