Religion, Revolution, and Digital Humanities: A Guest Post from Kate Carte Engel

Today I'm thrilled to share a guest post from Kate Carte Engel, an Associate Professor of History at Southern Methodist University. If you don't know of Prof. Engel from her important work on the religious and economic history of the Moravians, you might know her from her previous appearances here on the blog. What you may not know, however, is that this semester Prof. Engel has been working with her students on a digital humanities project on religion and the American revolution. I had the good fortune of watching the project unfold as the class blogged about their work. So I asked Prof. Engel if she would consider reflecting upon the experience for RiAH. Below are her thoughts--and visualizations!

|

| British Library, 1868,0808.10061,AN75238001 |

Religion and the American Revolution is a topic that tends

to linger in our national discussions.

Just recently, Jonathan

Den Hartog blogged about the fascinating questions raised on the subject by

Mark Noll’s new book. Those on the right

regularly insist that the United States is a Christian

nation because of something or other that happened in the Revolutionary

era, it's part of the school

curriculum in Texas, and the power of Christianity alongside our founding

documents in our civil religion keeps the subject on the table.

This semester I tried a new experiment. We did a digital humanities unit in which the

students investigated religion in American newspapers between 1763 and 1789,

then we built a website

around their findings. (I also blogged about

the process along the way.) The pedagogical goal was to shift the conversation

from my telling them where religion did and didn’t matter in the Revolution to

one in which they discovered, on their own, how complicated that question

was. The students and I spent about six

weeks on the project. This was dramatically

more than the one or two weeks the topic usually gets (I short changed the

early republic), but it matches the importance of public interest in the

subject.

In a bloggish-vein of true confession, I had no idea what I

was doing. (There have been great discussions on this blog about digital

humanities and digital

pedagogy, and the work of people like Chris

Cantwell and Lincoln

Mullen inspired me to try this.) Now that it’s over, however, I’m struck by the

potential for a project like this to participate in the public conversation

about Religion and the Revolution broadly, not despite but because it represents undergraduate-level work.

Viz., in two parts.

First, using digital humanities increased the time they spent

researching and decreased the amount of time they spent writing. I had to familiarize the students with a particular set of tools—in our case,

Zotero, Paper Machines, and Readex’s American Historical Newspapers—and then

cajole them into doing the grunt work of transcribing, for which there was no

shortcut. This often frustrating process

got the students to think about the nuts and bolts of how history is done and,

by extension, how different the past is from the present. They had to deal with place and

chronology in a very close way, as a part of choosing their newspaper sources. They also had to find religion. One student, for example, assumed he’d find sermons in the

newspapers, because that would be how pastors would communicate the

religious significance of the Revolution.

Another student assumed that because clergy were more important then,

the names of religious leaders would be all over the papers; they weren’t.

The second way this process worked was in the product. Each student produced a blog post and a

visualization about his or her subject. Because

they were going onto a website, they had to communicate

with a broad audience. Instead of

teaching students—in SLO language—to “think critically and historically and

demonstrate that thinking in prose” (research paper), students had to learn to

communicate something about the past to their contemporaries. Even when that meant discussing was how difficult

it can be to find a simple answer in the past.

|

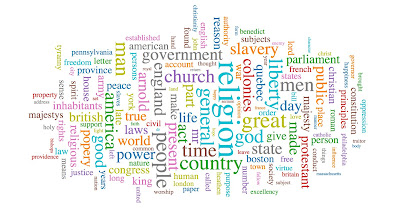

| A word cloud of major terms used in the students' work. |

Doing a website as a class project, in place of independent

research papers, is relatively new to me. (I did one a couple years ago on religion and our founding

documents.) But I’m coming around to the way of thinking that it is

actually more effective. I don’t want my

students to have specialized knowledge they do nothing with. I want my students to become ambassadors for

the humanities and historical thinking.

I want them to be the people at the Thanksgiving table who say, “well,

maybe Washington was devout or maybe he wasn’t, but I’m curious how we’d decide.” Of course, I’m not the only person who’s

thinking about this. Elesha Coffman’s

students at the University of Dubuque have been blogging Calvin’s Institutes. At the

University of Wisconsin, Professor Amos Bitzan had a group of

students trace the family history of one particular

Holocaust victim and her descendants in Racine, Wisconsin. At Western Carolina University, the students

of Professor Honor

Sachs have created a website on the Revolution in North Carolina.

All of these subjects—the influence of great thinkers, the

Holocaust, the Revolutionary War—compel ongoing interest from the public. Helping students to turn these broad topics

into specific questions, and putting their findings out there in all their

student-ness, demonstrates in an easily accessible way that there are no simple

answers. History is irreducible. Using methods from the digital humanities,

especially maps and visualizations, multiplies exponentially the kinds of

questions and particularities that can be asked and presented in this

format. This semester I gained a lot of

experience about how better to organize class time around this kind of project

and how to integrate it into other kinds of pedagogy. I’ll definitely be back

doing this again, building more digital websites about religion and the

revolution. Next time I won’t dread it as a week in the syllabus that misses

the point, but rather welcome it as a topic the students can help me explore.

Comments