Family Values and the Rise of the Christian Right. An interview with Seth Dowland.

Samira K. Mehta

Samira K. MehtaSeth Dowland. Family Values and the Rise of the Christian Right. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015)

SKM: Seth, first of all, as someone who also works on

religion and the American family, I am so excited to have your book in my

hands. I have been teaching your article of a similar name (published in Church

History in 2009) for years and expect to make similar use of the book.

SD: Thanks, Samira -- both for your excitement about the

book and for doing this interview.

SKM: I was really struck by an argument that you make in

chapter 2, “Textbook Politics,” that at issue for Christian schools was not

only the content of the education, but also the manner of inquiry, essentially

an educational system that prioritized top down instruction versus exploration

of concepts. Until you said that, I would have pointed to content based

differences such as: Were the Founding Fathers Christian or not? Do we include

histories of women or not? Do we teach evolution, creationism, or both?, but

you make it clear that there are very distinct pedagogical approaches. Would

you say more about that difference?

|

| Image courtesy of Liberty Christian Academy |

In the book I argue that such an approach to education emerged from a couple evangelical beliefs. First, evangelicals believed God had set up authority structures to govern society. Undermining authority went against God’s plan. Second, American evangelicals’ approach to scripture encouraged a robust faith in the determinative power of written texts. As Norma Gabler put it, “textbooks mold nations because they largely determine how a nation votes, what it becomes, and where it goes.” They worried that the pedagogical innovations offered by new textbooks went hand in hand with cultural relativism, and they determined to put the nation back on track by returning to old, didactic methods of instruction.

SKM: And in some ways, that structure versus content

question was echoed in internal evangelical debates about homeschooling as

well, yes?

SD: That’s right. One of the more unusual alliances I

discuss in the book came in the early 1980s, when conservative evangelicals

joined forces with John Holt, a liberal who published the most prominent

homeschooling magazine in the 1970s, Growing Without Schooling. Holt believed

that public schools stifled students’ creativity and advocated an approach

called “unschooling,” which would allow students to follow their curiosity and

discover things for themselves.

This approach obviously conflicted with the top-down

authoritarian approach preferred by conservative evangelicals, but they

partnered with Holt initially since his was the largest national homeschooling

organization in the early 1980s. By the late 1980s, however, evangelical

homeschoolers had formed their own organizations and developed independent

publishing houses, such as a Beka Books and Bob Jones University Publishers.

Evangelical homeschooling magazines carried advertisements for surplus school

desks so that moms could re-create the traditional classroom in their living

rooms. Such an approach was antithetical to Holt’s unschooling philosophy,

which lost ground relative to the massive influx of evangelical homeschoolers

in the 1980s.

|

| Image courtesy of Bill Tiernan |

SD: Evangelical attorney Michael Farris founded the Homeschool

Legal Defense Association (HSLDA) in 1983. He promised to defend any HSLDA

member charged with resisting compulsory education laws. Such prosecutions were

rare, but they were still happening in the mid-1980s. Homeschoolers who refused

to submit to state certification procedures occasionally found themselves in

court, where they tried to make various constitutional defenses of a right to

teach children at home, without any state oversight. The most common tactic for

evangelical homeschoolers was to cite the First Amendment right of free

exercise. Only one case to that point had successfully defended home education

on a First Amendment basis: 1972’s Wisconsin v. Yoder. In the Yoder decision,

the Court carefully circumscribed the right of home-based vocational education

to the Old Order Amish, a group with “a history of three centuries as an

identifiable religious sect.” Evangelicals were generally unsuccessful at

defending their right to homeschool using the Yoder precedent.

Homeschoolers had marginally better success at defending

homeschooling by appealing to the 14th Amendment, which provides for equal

protection and due process. In particular, evangelical homeschoolers cited the

Supreme Court’s 1925 decision in Pierce v. Society of Sisters, which prevented

states from requiring attendance at public school and held that “the child is

not the mere creature of of the state.” Pierce was used as a precedent in the

1973 Roe v. Wade decision, which permitted women to terminate a pregnancy and

provided for parents’ rights to make private decisions about the bearing and

rearing of children -- decisions like choosing to educate children at home, for

example. Although one homeschooling advocate noted that Roe provided a strong

legal precedent for defending homeschoolers’ rights against state interference,

evangelicals in the 1980s were trying to overturn Roe. So they mostly stayed

away from making that argument.

SKM: Were evangelicals concerned that if they ever

managed to have Roe v. Wade overturned, homeschooling rights would crumble?

SD: This question gets to the heart of the book’s

argument: conservative evangelicals made the family the central unit in their

political rhetoric because they worried that the language of equal rights would

enable humans’ worst tendencies to run unchecked. They rejected the Court’s

reasoning in Roe that abortion was solely a woman’s choice. Instead, they

argued that abortion involved a family -- a father, mother, and unborn child.

By rendering abortion as a family decision, the Christian right crafted a

political rhetoric that guarded against government overreach without embracing

the notion that everyone could do as they please. Evangelicals believed men and

women had particular roles to play, and they saw those roles epitomized in the

family.

I’m hesitant to say that evangelicals were concerned

about the the possible side effects of an overturning of Roe, but they were

certainly aware of the need to challenge the Court’s assumptions about privacy

rights. Conservatives wanted to protect families’ right of privacy, but they

were unwilling to embrace the right of privacy outlined by Roe, which, in their

minds, undermined the family.

SKM: As you answer this question, please keep in mind

that I am someone whose mother put an ERA Yes! button over her crib: One of the

things that find most interesting, in studies of conservative women’s groups is

the idea that feminism erodes women’s rights, that, essentially, feminism is

not only bad for men and children, but for women. The family values agenda,

with its separate spheres, is seen as healthy, and even empowering for women.

Could you say more about that particular juxtaposition?

SD: Because most evangelicals believed that God had laid

out distinct roles for men and women, they challenged second-wave feminists who

argued that women ought to seek pay parity, or government-supported daycare, or

equal representation in boardrooms. These transformations would, in their

minds, devalue motherhood. Anti-feminist women were careful to defend women’s

essential equality with men, but they argued that feminists mistook equality

for sameness. Anti-feminist women argued for separate (spheres) but equal. The

backlash against the Equal Rights Amendment came about as anti-feminist women

embraced Phyllis Schlafly’s characterization of the ERA as anti-woman. Schlafly

argued that current laws--if correctly enforced--already provided women equal

protection. She said that ERA would go beyond the wishes of most women and

would force women to abandon their high calling as wives and mothers (by, for

instance, requiring them to register for the draft). They saw the suburban home

not as a type of “concentration camp” (in the famous words of Betty Friedan)

but as an expression of God’s will for their lives. Feminists who wanted to

encourage women to make choices other than embracing motherhood became “enemies

of the family.”

SKM: Scholars of conservative women often note the irony

of women leaving the home to defend their right to stay in it. If the women you

write about believe in a Biblical mandate to stay in the home, how do they

navigate being called to political life?

SD: This one was easy for conservative evangelical women:

they were justified in their political activity as long as they predicated such

activity on their roles as wives and mothers. Textbook watchdog Norma Gabler

went to Texas state adoption hearings for decades (and made publishers “quake

with fear” that she would discover errors or offensive language in their

texts), but always with the rhetorical standing of a mother aggrieved about her

son’s textbooks. Anti-gay activist Anita Bryant called her campaign to prevent

gays and lesbians from becoming public school teachers “Save Our Children.”

(And Bryant quickly disappeared from the spotlight after she divorced,

suggesting the importance of marriage among pro-family leaders.) Bev LaHaye

signed her fundraising letters as,

“Author, Lecturer, Mother, and Pastor’s

Wife.” These women believed that political activity was legitimate as long as

they did it in defense of their families. Such beliefs resulted in a peculiar

position during the 2008 campaign, when a faction of conservative evangelicals

defended Sarah Palin’s right to run for the vice presidency so long as she

didn’t seek leadership in the church or her family. Outsiders were mystified,

but that position depended on the particular norms laid out by the pro-family

movement: women could range far outside the home as long as they embraced their

role within it.

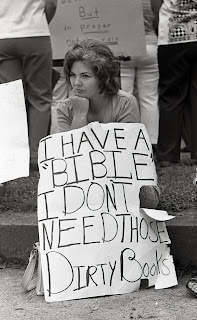

|

| Image courtesy of Stonewall Museum & National Archives |

SKM: The abortion chapter addresses one of the most

interesting aspects of the abortion debate, which is that the pro-life

position, formerly seen as the terrain of Catholics, becomes a site of

Evangelical-Catholic cooperation. What strikes you about that partnership? How

did each group have to shift to accommodate the other?

SD: The most striking thing was how quickly these two

groups came together in the late 1970s. After all, just over a decade earlier,

conservative evangelicals voiced some of the loudest concerns about John F.

Kennedy’s Catholicism in the 1960 election. But by the late 1970s, there was

significant “co-belligerence,” in the famous words of Francis Schaeffer. I

think there at least a couple reasons why.

First, evangelicals were never pro-abortion, even if they

were not the most vocal critics of the Roe v. Wade decision in its immediate

aftermath. As Matt Sutton’s American Apocalypse demonstrates, some

fundamentalists were decrying abortion in the 1930s. L. Nelson Bell, who was

one of the leading evangelical voices against Kennedy in 1960, was railing

against abortion in the late 1960s and early 1970s. So even if Roe didn’t

immediately mobilize evangelicals, it wasn’t exactly popular among them,

either.

Second, conservative Catholics had already begun to find

common cause with conservative Protestants on social issues, even as they

drifted away from liberals in their own church. Illinois Catholic Phyllis

Schlafly led the anti-ERA movement and found her greatest support among white

evangelical southerners (nearly all of the states that didn’t ratify the

amendment were in the Sunbelt). The STOP ERA movement was a precursor to a

larger pro-life movement, and in many ways the enemy was the same:

“anti-family” feminists.

SKM: You have the section on gay rights listed under the

“father” heading, which I found striking in a year that has seen significant

political wins for the gay rights movement, at the same time that women’s

rights have seen notable rollbacks. Can you talk about the masculine quality of

the opposition to gay rights movements? Does it matter to the movement that we

talk much more about gay rights than about gay and lesbian rights?

SD: The gay rights chapter was the hardest to fit in my 3

sections (children, mothers, fathers), but I think it’s fair to place it in the

fathers section. For one thing, conservative evangelicals worried most about

gay men preying on their children. The sources I researched featured countless

warnings about the pathologies and depravity of gay men, who would “recruit”

young boys to the “homosexual lifestyle.” Lesbianism seemed almost an

afterthought to conservative evangelicals, and lesbians and feminists were

frequently lumped together in pro-family political rhetoric. Also, conservative

evangelicals worried about weakness in American men, and they saw gay rights as

a symptom of that weakness. When evangelicals soured on Jimmy Carter, they used

unsubtle metaphors to impugn his manhood: Carter “comes out of the closet” on

military preparedness; or, “White House Conference on Families Shapes Up as Gay

Affair.” Much of the opposition to gay rights derived from a normative

heterosexual masculinity, so it made sense to locate that chapter in the

fathers section.

SKM: Last semester, I taught a class entitled Gender and

Sexuality in American Religion. I got some pushback from men in the class about

how “woman heavy” the list of authors was. On the one hand, I was frustrated,

because another class was similarly dominated by texts by men and no one even

noticed. On the other, part of what excites me about your book is that it is a

gender history that addresses constructions of familial gender roles and that

you are a man. Do you have thoughts about being a male scholar writing on

histories of gender?

SD: During the 1970s and 1980s, a vanguard of feminist

scholars demonstrated the patriarchal assumptions that have dominated religious

history. For those of us trained in the generation after these feminist

scholars made gender a “useful category of historical analysis,” ignorance of

the role gender plays in religious history isn’t an option. Even so, I was

surprised that evangelical sources reflected an obsession with gender as

clearly as they did. I didn’t have to dig too deeply or read between the lines

to discover how important gender norms were to evangelicals; they made the

point loudly and repeatedly. My book, in one sense, simply illustrates the

gender norms that evangelicals constructed. I am hardly the first scholar to

notice how important gender and sexuality were to white evangelicals in the late

twentieth century.

Sadly, neither the demographics of your reading list nor

your students’ comments surprise me. Women have produced the lion’s share of

great scholarly work on religion and gender, and masculine norms remain less

visible and less studied in scholarly literature. Many male students are still

apt to equate “gender” with “women”; a 15-person course I taught last year on

Religion and Gender enrolled all women! (This isn’t meant to be

self-congratulatory: I never took a class on gender as an undergraduate,

either.) But it does speak to the work still in front of us, both to normalize

the study of gender among men and to excavate those sites where the role of

gender is more hidden. I take this to be a feminist task, and I hope to pursue

it further in my next big project: a history of Christian manhood from the era

of “muscular Christianity” to the present.

Comments