Key Terms in Material Religion: An Interview with S. Brent Plate

Samira K. Mehta

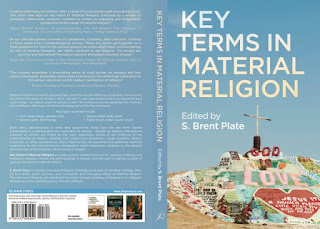

On December 17 (ten days from today), Bloomsbury Academic

will be releasing Key Terms in Material Religion, edited by S. Brent Plate. The

title is currently available for pre-order at your local independent

bookseller!

SKM: Professor Brent Plate, thank you for agreeing to be

interviewed here on Religion in American History (and thank you for commenting

on some of my other posts.) It is great to get this chance to get to know you

and your work. This is the first time that I, in this interview series, have

spoken with the editor of an edited volume and so I wanted to concentrate on

that process for some of the interview. Let me start with what seems like the

most basic question: what led you to see a need for a “key terms” book for the

study of material religion?

SBP: Thanks for agreeing to discuss an edited volume. I’ve

spent a sizable amount of my professional life editing, and I continue to find

it a rewarding experience. It really allows for some great collegial

connections, something that I miss often when I’m writing my own work.

As for the specifics of this volume, the initial answer is

that after several years of editing the journal Material Religion my fellow

editors (Crispin Paine, David Morgan, and Birgit Meyer) and I realized that

this field of study has really congealed into something strong and influential.

Without setting too strict limits on what “material religion” means, we wanted to

supply students and teachers with a range of inroads to this way of research.

Key Terms in Material Religion really began in an editors’

meeting at Duke University several years ago. Crispin, David, Birgit, and I

were thinking about potential special issues for the journal and hit on the

idea of doing a special issue as a “key terms” issue. So we commissioned 19

short articles on key terms, and published that as our March, 2011 issue. The

response to the issue was great, and it warranted further work. With the

agreement of my co-editors, I took the initial articles, asked authors to rewrite

a little (some did, some didn’t), and then I doubled the size, commissioning

another 18 articles for the book, and writing up an introduction. The result is

a 37 entry volume (it’s quite an editing challenge to wrangle three dozen

academics!).

SKM: When you sat down to draft a list of key terms, what

served as your guiding principle?

|

|

Taco Truck, East Los Angeles.

From the entry "Race" by Roberto Lint-Sagarena.

Photo by Lint-Sagarena.

|

With that said, my aim was also one of diversity. I tried to

get a diversity of examples from around the world, a diversity of religious

traditions represented, written by scholars working in various fields and

various places. (Unfortunately, this only includes scholars working in the

English language.) There’s no perfect balance, but contributors come from

fields of museum studies, art history, cultural anthropology, sociology, media

studies, as well as religions in the Americas, Asian religions, African

religions, and European religions.

SKM: Obviously, there are more terms than could be included

here. Was there a logic to what ended up in the book and what did not?

SBP: Yes, it could always have been otherwise. As anyone

who’s edited a book knows, a lot of the process is punctuated like that

interruption to a television show, “Due to technical difficulties beyond our

control, we cannot bring you tonight’s episode of Happy Days.“ Many logistical,

professional, and sometimes personal limitations affect the final product.

The reality of this project is that the selection depended

on the gelling of three things: a useful key term, a prominent scholar who

could write on that critically and creatively, and do it in the space and time

allotted. We academics tend to believe we live a life of the mind, but our

thinking is always constrained by material realities including the publishing

industry, the technologies of publication, and time itself. We may have the

Platonic form of the ideal book in our mind when we set out, but scholarship is

always shaped by material structures.

SKM: Without asking you to get into the nitty gritty of this

person versus that person, how did you select the authors for the various

terms? Did you go from term to author or author to term?

SBP: It was a bit back and forth from author to term/ term

to author. The terms were important, but it was also important to include

notable, internationally recognized scholars. Contributors include former AAR

presidents, chairs of prominent departments and research centers, and authors

of many award-winning books.

|

Airline flight with screens in seat backs.

From the entry "Technology" by Kathryn Lofton.

Photo by S. Brent Plate

|

SBP: Yeah, there’s a real sense of this being a “sampler,”

which can be a negative thing in academia, but I’d argue there are important

uses of brevity and sampling. For one, our contemporary culture is immersed in

the short form, from 140-character tweets to Oxford University Press’s “Very

Short Introductions.” Information is spread out, and sometimes thin, which I do

not believe to be a bad thing. (“Depth” and “length” have their own problematic

ideological histories.)

I had the classroom in mind as I edited the volume, and

while it’s not a standard structured “textbook,” I think a lot of creative

instructors can make use of it. It is modular, adaptable, and can fit in with a

variety of ways of teaching not only “material religion,” but “methods and

theories” and even “introduction to religion” courses.

With that in mind, I asked authors to keep to <2500

words, and use a case study as a touchstone. Compared to a typical academic

essay these are short, but you can do a lot with 2500 words, and I’m thrilled

with how much is packed into these pieces.

SKM: Are there limitations to the case study approach?

SBP: All approaches have limitations, and as hinted at above

the brevity may be one. Many will read and want more. But they’re in luck!

There is much more out there on all these topics, and bibliographies can lead

in the proper directions. In fact, many of the contributors have written entire

books on the topics.

The other limitation may be in the minds of the readers, and

that is our sometimes academic myopia in not being able to think analogously.

For example, one might read Ivan Gaskell’s creative piece on “Display” that

looks at a curious convergence of displays in and around Trafalgar Square,

London, but not be able to imagine how that story relates to anything in their

own space and time. Or, a look at the mapping project in Mumbai that Anita

Patil-Deshmukh writes about in the entry “Maps” might suffer because readers

don’t see relations to their own city streets. In fact the specifics of these

case studies have relevance across distances, not only for seeing similarities,

but differences as well.

SKM: One thing that people may not realize (in part because

it is not really reflected in the price) is that each case study as a full

color image--an important material dimension, but one that continues to

emphasize the role of the visual in material culture studies.

SBP: One thought experiment I always pose to my students is

this: Imagine that the sense of smell, instead of vision, was the primary

sensual mode in modern western society. Would we have invented olfactory

recording and observing devices instead of optical cameras and microscopes?

What if the Internet were not so doggedly audio-visual, but included scents,

linked through some sort of portable, handheld smellometers that would clue us

into our surroundings, records scents and plays them back for future reference?

(Such devices do exist, by the way, they’re just not popular.) The experiment

goes a step further to ask: Or was it the cameras and microscopes that made

vision the primary sense of modernity?

So, yes, the material realities of modern academic

publishing are in themselves constructed around vision (reading books is the

most acutely visual activity humans have constructed), and the images reiterate

that. But images can be used as primary evidence, and it’s been great to work

with Bloomsbury who were happy to reproduce full color images. It really is a

lovely book!

|

|

Shelf of Jewish cookbooks.

From the entry "Food" by Nora Rubel.

Photo by Rubel.

|

SKM: This is, of course, the Religion in American History

Blog and you include many key voices in the study of American religion. How do

you see the role of American religion in the examples and scholarship that you

are treating?

SBP: There are indeed many key voices in U.S. religions: Tom

Tweed, Katie Lofton, Bob Orsi, Debbie Whitehead, Nora Rubel, David Morgan, Ann

Taves, and Isaac Weiner are all here. Moreover--again back to the analogous

thinking--many of the case studies from Africa, Asia and elsewhere can be

thought about on U.S. turf. For example, we might think about how the Central

African “masks” that Al Roberts writes about can be thought of in North

American rituals of masquerades and Halloween, or how “dress,” as Annelies

Moors tells it, impacts our understanding of U.S. religions (among others, Lynn

Neal is writing about this now.)

And as many of the posts on this blog site show, there has

been a decided shift toward the material dimensions of religious life in

studies of U.S. religions, so I think the volume merges well with other

currents of study.

SKM: As someone who is a scholar of American religion teaching a senior seminar in Religion and Material Culture this spring, that balance appeals to me, because it gives me a base with which I am comfortable, as well as pushing the readings outside of my own comfort zone. Are there other fields that are as well represented as American religion?

SBP: In an age of massive human migration, the ebb and flow

of cultures, ethnicities, and languages

should challenge all of us to rethink

our comfort zones. I think part of what “material religion” as a field of study

can do is resituate our questions, to make us query the objects, spaces, and

role of the body in comparative studies. We have to be attentive to the look

and feel of others, to family rituals (right, Samira?!) not just some

abstracted doctrinal ideas. S. Brent Plate is the Managing Editor of Material Religion: The Journal of Art, Objects, and Belief. He is a visiting associate professor of religion at Hamilton College. He is the author, most recently, of A History of Religion in 5 1/2 Objects: Bringing the Spiritual to its senses, which Samira previously reviewed for this blog. He is particularly interested in "what religious humans look at, smell, and otherwise sense, and how religious traditions continue, in part, because they work to train our senses in particular ways."

Comments