What Can You Do with Denominational History?

I recently read Thomas Kidd and Barry Hankins's Baptists in America: A History (2015). I must have liked it, since my father, for many years a Baptist pastor, says that I've tried to send him copies more than once. This book deserves a proper review, perhaps paired with David Bebbington's Baptists Through the Centuries: A History of a Global People (2010). But for today I want to use the book to think through what a denominational history can accomplish. Here are a few thoughts about the particular set of things the book is able to accomplish because it is a denominational history.

- A denominational history can cross the color line.

This book is not filled with "Baptists" and "black Baptists," where unmarked Baptists can be assumed to be white. Rather, Kidd and Hankins are careful to write "white Baptists" when they mean white Baptists, and write "black Baptists" when they mean black Baptists. A denominational history is of course far from the only way to discuss race in the context of religious history. Yet we can contrast the effects of the decision to focus on Baptists with the decision to focus on, say, evangelicalism. Recent histories of evangelicalism or fundamentalism tend to take white Christians as their subjects, whether or not there are good reasons to question that demarcation, acknowledge the color line, and leave it at that. If race is the single most-important category in U.S. history (and it is), then our histories of U.S. religion ought to be able to discuss race at least as well as this denominational history.

- A denominational history can describe denominational distinctives.

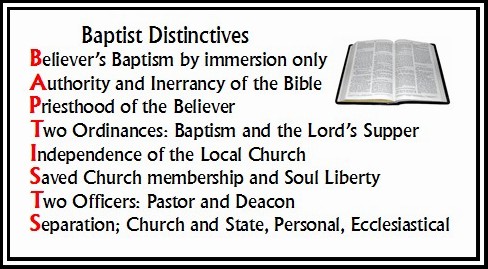

Baptist distinctives from this church website.

Baptists love their "Baptist distinctives," by which they mean a set of beliefs, practices, and ecclesiastical structures which collectively distinguish them from other Christians. (See the image for a common formulation.) Kidd and Hankins quite rightly ask whether "the time is long past when we can make broad claims about what makes Baptists distinct" (251). Instead they organize their book around the argument that Baptists are "insider-outsiders" in this sense: Baptists were once at the very margins of church, law, and culture, and even though they have since become in many places the leading denomination with enormous political and cultural influence, they still regard themselves as an embattled minority. This ought to be obvious to Baptists but it is not, like a quirk in your family which you never noticed until your spouse pointed it out. (For that matter, if the journalists and pundits who talk about religion could learn this basic idea, then there might be a little more light in public commentary.) The distinguishing features of denominations are not the only thing worth understanding about American religious history, but like the family you come from, they go a long way towards explaining why different groups do what they do.

- A denominational history can be an institutional history.

What is the difference between the National Baptist Convention, USA, Inc. and the National Baptist Convention of America, Unincorporated? Well, Kidd and Hankins can tell you. It actually turns out to be an interesting story about Richard Henry Boyd, an influential black Baptist publisher, and the struggle to control networks of influence within a denomination and through the legal system. It seems to me that we are pretty far away from the mythical bad old days where denominational history was just a history of denominations, proper. The reasons Baptists split and joined forces in struggles over denominational politics are actually revealing proxies for larger issues.

- A denominational history can connect to American history.

You might think that a denominational history would tend to be narrowly focused inward and not have a connection to the larger history. Kidd and Hankins convincingly pin their narrative to the larger narrative of U.S. history. Two examples: the sectional crisis over slavery connects to the split between northern and Southern Baptists, while the same denominational struggles were re-fought in the civil rights era. Actually, there are so many connections here that I suspect it was probably a constant problem for the authors to figure out how much of general U.S. history they had to fill in for their readers.

- A denominational history can appeal to, you know, people who read books.

I don't know how many copies of this particular book Oxford is moving; I hope a lot. But it seems to me that among the many potential audiences for a work of history, one obvious one are the members of a denomination themselves. (An interesting empirical question: which denomination or religious group reads the most? Someone must have the answer.) Framing a book to help its subjects understand themselves is a worthy goal.

Comments

As for the religious group who reads the most of their own history, it has to be Mormons, right?