“It’s Not Sissy to be a Christian”: Playing Indian, Sports, Evangelicalism at Kanakuk Kamps

Today's guest post comes from Hunter M. Hampton, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Missouri, who is currently the visiting scholar at the M.J. Murdock Charitable Trust in Vancouver, Washington. I had the pleasure of meeting Hunter at the OAH annual meeting earlier this year. His post is based on the paper he gave as a part of the panel "The Myth and Reality of Indigenous Childhood."

Hunter M. Hampton

Just as much as a week of pipe-cleaner crafts and dodgeball is an important summer ritual for American Christians, so is a term at summer camp. Each summer nearly 11 million children and adults attend a summer camp in the United States. In 2012, camping was a fifteen billion, yes billion, dollar industry. According to the Christian Camp and Conference Association, more than 5.5 million people attend a Christian camp or conference each year, and “tens of thousands come to faith in Jesus Christ through that experience.” One of the largest Christian residential summer camps in the United States is Kanakuk Kamps. Located in the Ozark Mountains outside of Branson, Missouri, the camp has never missed a summer since its founding in 1926. Reading through Kanakuk’s brochures from 1950-1970 provides an interesting lens through which to view Kanakuk’s appeal to Cold War-era evangelical families. One key to Kanakuk’s success was its blend of playing Indian, sports, and evangelical Christianity.

The day a first-time camper arrived, they were placed in one of two American Indian tribes, Cherokees or Choctaws. According to the camp brochure, “The hatchet is dug up the first week of camp and a battle royal is between the two tribes.”[1] Over the course of the summer, the two tribes competed in football, baseball, basketball, swimming, marksmanship, and archery to earn points for their tribe.[2] At the end of the term, a winner is decided and “the hatchet buried with ceremony until the following summer.”[3] Reflecting on their time at camp, former campers repeatedly recalled their fond memories of tribal competition, and offered their well wishes to fellow tribesmen. The potency of imitating American Indians appeased a desire for an authentic experience in nature and left an indelible mark on the campers for the rest of their lives.

Aside from the ceremonies and competition, Kanakuk offered children the opportunity to learn from the Indians that previously occupied the land. Each day campers took a course in “Indian Studies.” Here they learned that “the camp is situated in old Indian country, and many relics of the early Indian life are found: arrow heads, spearheads, and pieces of pottery being among those collected.”[4] Each class had an instructor allegedly knowledgeable of Indian customs and traditions. Learning about Indian culture afforded campers instruction on properly playing Indian. These types of lessons inspired one father to declare “if he had to have his children miss summer camp or a year in school he would prefer that they miss the year’s schoolwork.”[5]

One sport that rose in significance and popularity at Kanakuk from 1950 to 1970 was football. In 1951, football shared a headline in the brochure description with softball. The description briefly stated, “The fundamentals of football are emphasized — passing, kicking, dodging, running and the line play, with the game being played in modified form.” Comparatively, softball was described as “the great national pastime [that] is always popular, and is one of the leading sports in camp.”[6] By 1965, football gained its own section and overtook the popularity of softball. The new description of football highlights its heightened appeal. It proclaimed, “Football and football conditioning are extremely important parts of the sports program… ‘flag football’ presents an ideal balance between contact football and summer weather.”[7]

Kanakuk enhanced its football program with the counselors it hired. One example was Ray Schoenke. Born on September 21, 1941 in Wahiawa, Hawaii, Ray moved with his family to Dallas, Texas. He played football at Southern Methodist University where he earned first-team All Southwest Conference and Academic All-American honors in 1962. After graduating with a degree in history, the Dallas Cowboys drafted him in the 11th round of the 1962 NFL draft. For the next twelve years he played for the Cowboys and Washington Redskins. He spent his falls playing in the NFL but his summers working as a counselor at Kanakuk. The legacy of influential football players that worked and attended Kanakuk includes four Heisman Trophy winners: Doak Walker, Dave Campbell, Sam Bradford (an actual member of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma. I’m not sure of his Kanakuk tribe), and Johnny “Football” Manziel.

Each summer at Kanakuk, campers (including Johnny Football) heard a sermon delivered by the camp director entitled “The Christian Athlete.” The sermon linked athletic performance with evangelical Christianity. It began with a story about a football coach who decides to put in a young backup defensive player for one play. The boy goes in and makes a great tackle. So the coach decides to leave him in the game. When the final seconds tick off the clock, the team carries the young man off the field in victory. After the game, the coach asks the boy where he found this ability. The boy reminds the coach that his blind father passed away a week prior, and the boy said, “Well, coach, this is the first game my father has ever seen me play.”[8] In explicating the story, the preacher illustrates the reciprocal relationship between the boy’s Christian faith and athletic performance. By the end of the sermon, little doubt remains that Jesus loves football and helps his followers on the playing field of life. The sermon concludes with a call to the young campers, “It is not sissy to be a Christian, nor is it any easier for an athlete to be a Christian. But it is tremendously important for athletes to be Christians because ‘the athlete has the added blessing of physical prowess, an endowment to use as his pulpit.’”[9]

The foundation of Kanakuk’s theology and mission was the “I’m Third” motto. In a sermon about the “I’m Third” life, campers learned about putting God first, others second, and themselves third. To make the point relevant, the sermon blended the vigor from playing Indian, sports, and Christianity. “The more we find out about the Jesus story, we find how tough and rugged He really was, capable of getting mad when it was necessary, capable of being physically strong and tough, living outdoors all the time.”[10] The Jesus depicted here is not the light-skinned, passive, well-groomed man with a halo shinning around his head. Rather, the I’m-Third Jesus is a gruff, muscular outdoorsman. After highlighting Jesus’ physique, the sermon continued, “Jesus Christ kept things so simple. He put everything on the bottom shelf as we say. He kept it right down where we could get to it.” The key to discovering Christ’s simple message was the Bible. “If I had one little book to give a man in business to help him make more money than anybody in the world, would he read it?” the preacher mused. “Of course, he’d read it. He’d memorize it. This book, called the Bible, is one of the keys to perpetual life and an ever present help to living this life.”[11] From raccoons to Jesus’ “Golden Rule”, Gene Stallings’ pregame football speech to Bible reading, the evils of smoking to serving your neighbor, the preacher wove together lessons about nature, physique, athletics, and putting God first, others second, and yourself third.

The lessons instilled at Kanakuk during the middle of the 20th-century remain in the mega-camp today. Children are still placed into Indian tribes. They still dress up in headdresses, loincloths, and war paint to dance around a campfire. They still play football and hire collegiate athletes. They still hear the I’m Third sermon. What is remarkable is that over the course of the 20th-century, American families grew ever attracted to what Kanakuk sold. In 1978, Kanakuk built a second camp, K-2, that hosts over 1,800 campers. In 1983, K-West was established with six two-week terms of 1,300 campers per term. In 1988, K-Kountry first hosted 1,100 campers age 8 to 13. And in 1992, K-7 opened and held 2,800 one-week campers. In 2008, over 20,000 campers and 3,000 staff members spent their summer at Kanakuk. Now, Kanakuk consists of nine different camps, three camps for inner-city youth, a “gap year” program for high school graduates, and a Bible training school for college graduates. From age 7 to 24, Kanakuk offers a camp experience for you. With these numbers, the history of Kanakuk is not simply the history of one camp filled with fun pictures and incredible quotes. It is more than that. It is the history of longings within well-off, (mostly) white, evangelicals to encourage vigor and a connection to nature in an increasingly urban, affluent society. Untangling the significance of rituals, beliefs, and practices of places like Kanakuk and Vacation Bible Schools offer insight into why generation after generation of American’s send their children away each summer for training. I wholeheartedly agree with Michael Altman, someone does need to write a book on this subject, but maybe hold off until I finish my dissertation.

[1] Tribes, “Memories of Kanakuk are Forever,” 1951, Kanakuk Business Offices, Branson, MO.

[2] Sports, “The ‘K’ Kamps: Kuggaho for Boys, Kickapoo for Girls, Heart of the Ozarks,” circa 1929.

[3] Tribes, “Memories of Kanakuk are Forever,” 1951.

[4] Camp Activities: Indian Studies, “Memories of Kanakuk are Forever,” 1951.

[5] Why a Summer Camp, “The ‘K’ Kamps,” circa 1929.

[6] Football and Softball, “Memories of Kanakuk are Forever,” 1951.

[7] Football and Softball, “Memories of Kanakuk are Forever,” 1965.

[8] The Christian Athlete, Sundays to Remember, “Memories of Kanakuk are Forever.”

[9] The Christian Athlete, Sundays to Remember, “Memories of Kanakuk are Forever.”

[10] I’m Third, Sundays to Remember, “Memories of Kanakuk are Forever.”

[11] I’m Third, Sundays to Remember, “Memories of Kanakuk are Forever.”

Hunter M. Hampton

|

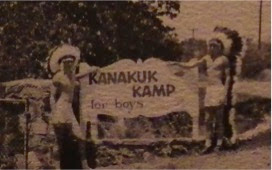

| Campers in front of camp sign circa 1950. Photo from "Memories of Kanakuk are Forever" |

The day a first-time camper arrived, they were placed in one of two American Indian tribes, Cherokees or Choctaws. According to the camp brochure, “The hatchet is dug up the first week of camp and a battle royal is between the two tribes.”[1] Over the course of the summer, the two tribes competed in football, baseball, basketball, swimming, marksmanship, and archery to earn points for their tribe.[2] At the end of the term, a winner is decided and “the hatchet buried with ceremony until the following summer.”[3] Reflecting on their time at camp, former campers repeatedly recalled their fond memories of tribal competition, and offered their well wishes to fellow tribesmen. The potency of imitating American Indians appeased a desire for an authentic experience in nature and left an indelible mark on the campers for the rest of their lives.

Aside from the ceremonies and competition, Kanakuk offered children the opportunity to learn from the Indians that previously occupied the land. Each day campers took a course in “Indian Studies.” Here they learned that “the camp is situated in old Indian country, and many relics of the early Indian life are found: arrow heads, spearheads, and pieces of pottery being among those collected.”[4] Each class had an instructor allegedly knowledgeable of Indian customs and traditions. Learning about Indian culture afforded campers instruction on properly playing Indian. These types of lessons inspired one father to declare “if he had to have his children miss summer camp or a year in school he would prefer that they miss the year’s schoolwork.”[5]

One sport that rose in significance and popularity at Kanakuk from 1950 to 1970 was football. In 1951, football shared a headline in the brochure description with softball. The description briefly stated, “The fundamentals of football are emphasized — passing, kicking, dodging, running and the line play, with the game being played in modified form.” Comparatively, softball was described as “the great national pastime [that] is always popular, and is one of the leading sports in camp.”[6] By 1965, football gained its own section and overtook the popularity of softball. The new description of football highlights its heightened appeal. It proclaimed, “Football and football conditioning are extremely important parts of the sports program… ‘flag football’ presents an ideal balance between contact football and summer weather.”[7]

|

| Ray Schoenke lifting weights at Kanakuk. Photo from "The Fifties and Forward: Media, Memories, and More." |

Each summer at Kanakuk, campers (including Johnny Football) heard a sermon delivered by the camp director entitled “The Christian Athlete.” The sermon linked athletic performance with evangelical Christianity. It began with a story about a football coach who decides to put in a young backup defensive player for one play. The boy goes in and makes a great tackle. So the coach decides to leave him in the game. When the final seconds tick off the clock, the team carries the young man off the field in victory. After the game, the coach asks the boy where he found this ability. The boy reminds the coach that his blind father passed away a week prior, and the boy said, “Well, coach, this is the first game my father has ever seen me play.”[8] In explicating the story, the preacher illustrates the reciprocal relationship between the boy’s Christian faith and athletic performance. By the end of the sermon, little doubt remains that Jesus loves football and helps his followers on the playing field of life. The sermon concludes with a call to the young campers, “It is not sissy to be a Christian, nor is it any easier for an athlete to be a Christian. But it is tremendously important for athletes to be Christians because ‘the athlete has the added blessing of physical prowess, an endowment to use as his pulpit.’”[9]

|

| A church service at Kanakuk, 1969. "Memories of Kanakuk are Forever." |

The lessons instilled at Kanakuk during the middle of the 20th-century remain in the mega-camp today. Children are still placed into Indian tribes. They still dress up in headdresses, loincloths, and war paint to dance around a campfire. They still play football and hire collegiate athletes. They still hear the I’m Third sermon. What is remarkable is that over the course of the 20th-century, American families grew ever attracted to what Kanakuk sold. In 1978, Kanakuk built a second camp, K-2, that hosts over 1,800 campers. In 1983, K-West was established with six two-week terms of 1,300 campers per term. In 1988, K-Kountry first hosted 1,100 campers age 8 to 13. And in 1992, K-7 opened and held 2,800 one-week campers. In 2008, over 20,000 campers and 3,000 staff members spent their summer at Kanakuk. Now, Kanakuk consists of nine different camps, three camps for inner-city youth, a “gap year” program for high school graduates, and a Bible training school for college graduates. From age 7 to 24, Kanakuk offers a camp experience for you. With these numbers, the history of Kanakuk is not simply the history of one camp filled with fun pictures and incredible quotes. It is more than that. It is the history of longings within well-off, (mostly) white, evangelicals to encourage vigor and a connection to nature in an increasingly urban, affluent society. Untangling the significance of rituals, beliefs, and practices of places like Kanakuk and Vacation Bible Schools offer insight into why generation after generation of American’s send their children away each summer for training. I wholeheartedly agree with Michael Altman, someone does need to write a book on this subject, but maybe hold off until I finish my dissertation.

[1] Tribes, “Memories of Kanakuk are Forever,” 1951, Kanakuk Business Offices, Branson, MO.

[2] Sports, “The ‘K’ Kamps: Kuggaho for Boys, Kickapoo for Girls, Heart of the Ozarks,” circa 1929.

[3] Tribes, “Memories of Kanakuk are Forever,” 1951.

[4] Camp Activities: Indian Studies, “Memories of Kanakuk are Forever,” 1951.

[5] Why a Summer Camp, “The ‘K’ Kamps,” circa 1929.

[6] Football and Softball, “Memories of Kanakuk are Forever,” 1951.

[7] Football and Softball, “Memories of Kanakuk are Forever,” 1965.

[8] The Christian Athlete, Sundays to Remember, “Memories of Kanakuk are Forever.”

[9] The Christian Athlete, Sundays to Remember, “Memories of Kanakuk are Forever.”

[10] I’m Third, Sundays to Remember, “Memories of Kanakuk are Forever.”

[11] I’m Third, Sundays to Remember, “Memories of Kanakuk are Forever.”

Comments

Thanks for the questions. Kanakuk never had any affiliation with the KKK, just an unfortunate coincidence of consonants. The name came from a real Kickapoo medicine man that lived in the middle of the 19th century. As far as the race question goes, Kanakuk was in the minority by not having an explicit segregation policy on the books. The campers were primarily, nearly exclusively, white, but I believe high cost of attendance, geographic location, and de facto segregation were the cause of this. For why the 20s, the interwar years were a boom-time for summer camps. Kanakuk is not unique in its start date, but is for its extraordinary growth.