Religion and Rosie the Riveter

Adina Johnson

I always feel that it’s worth noting that my June entries fall on June 6, the anniversary of D-Day. I take that as justification to reflect on religion in the era of World War II. Last year, Sean Brennan wrote about the Roman Catholic chaplain, Fr. Fabian Flynn. This year, we have another guest poster. Adina Johnson is a Ph.D. student in U.S. History at Baylor University. Her research is on women and religion during World War II. I’m delighted that she was willing to share a few thoughts with the RiAH blog. ~Jonathan Den Hartog

In the midst of World War II, the Seattle Times expressed the distinctiveness and value of a woman’s contribution to the war effort: "Men fight the war with bayonets, long hours at defense jobs, 'leisure' hours at air-raid drills. Women fight the war with stewpans, knitting needles, alarm clocks that go off at 4 o'clock in the morning, rudely awakened babies, unelastic budgets, fast-rising prices." The advertisement suggested a man might receive more glory for his efforts, but “women’s work” was just as important to America’s effort to win the war. For the Times, a woman’s service in the private sphere was as essential, and as patriotic, as a man’s sacrifice in the public sphere.

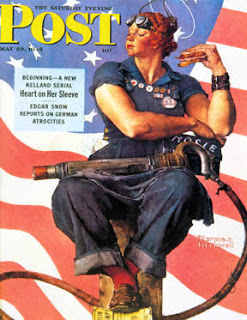

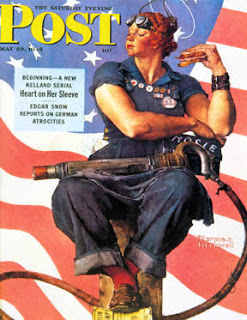

Iconic images from the American war effort such as Rosie the Riveter, Red Cross nurses, victory gardens, gold stars hanging in windows, and female WASP pilots all convey the importance of a woman’s contribution to the Allied cause, and the righteousness of her doing so no matter the cost. For conservative Protestants, however, the story was more complicated because of deep-seated ideals regarding the value of a woman’s presence within a Christian home. Conservative Protestant periodicals from the war years show that a woman who chose to become a soldier or war-worker held a precarious position within the Christian community. The press attempted to alleviate some of this unease by describing her public roles using the language of domesticity and spirituality, even as her work took her far outside the bounds of traditional Victorian womanhood.

No image would come to symbolize the role of American women during World War II more indelibly than “Rosie the Riveter”. The quintessential “Rosie” was a woman who exemplified patriotic femininity while working in a wartime factory wearing overalls and a bandanna. Indeed, many women entered the work force for the first time during the war, in traditionally masculine jobs. However, both mainstream Americans and conservative Protestants wrestled with the impact of this change. Both voiced concerns for the health of the family, and emphasized the necessity of other wartime roles for women, but the conservative Protestant press could never quite bring itself to fully affirm the idea of a mother or wife working outside the home.

No image would come to symbolize the role of American women during World War II more indelibly than “Rosie the Riveter”. The quintessential “Rosie” was a woman who exemplified patriotic femininity while working in a wartime factory wearing overalls and a bandanna. Indeed, many women entered the work force for the first time during the war, in traditionally masculine jobs. However, both mainstream Americans and conservative Protestants wrestled with the impact of this change. Both voiced concerns for the health of the family, and emphasized the necessity of other wartime roles for women, but the conservative Protestant press could never quite bring itself to fully affirm the idea of a mother or wife working outside the home.

The experiences of conservative Protestant women in relation to war work reflect the experiences of American women as a whole. Some entered the work force while others stayed home with their families. Pat Williams, a Southern Baptist woman from West Texas, observed that many women in her church worked at a munitions plant about thirteen miles away, especially those women whose husbands were in the service. She recognized that this was a new phenomenon, “Before then women basically didn’t many of them work outside the home, nurses probably, school teachers, and a few secretaries . . . But most women just stayed home.” Donna M. Panknin Denton, from Waco, Texas, worked two jobs during the war. Her first job was playing the organ or piano for local funerals. Her primary job, though, was working at a war plant that manufactured ammonia and nitric acid. She noted, “Of course, I was in the administrative building,” a comment that revealed her assumption that women wouldn’t work in the factory itself. Most conservative Protestant women were able to navigate the potential conflict between war work and their responsibility as Christian wives and mothers without much trouble.

The conservative Protestant press took a decidedly more critical stance on “Rosie”, their articles focusing on war work’s dangers for families and marriages without directly renouncing it. They were pushing back against the pro-“Rosie” agenda of the secular press and warning conservative women against neglecting their primary duties in the home. A poem published in the Baptist Watchman-Examiner displays the mixed-feelings conservative Protestants felt towards Rosie:

The conservative press never placed the principles of Christian domesticity and piety on the back burner, even during World War II. A Christian “Rosie” could be honorable as long as family and the home always stayed her top priority. The conservative Protestant media differed from the secular media in that Christian authors and editors never wholeheartedly endorsed women in the factories, even as conservative women sought out these roles along with their mainline counterparts.

I always feel that it’s worth noting that my June entries fall on June 6, the anniversary of D-Day. I take that as justification to reflect on religion in the era of World War II. Last year, Sean Brennan wrote about the Roman Catholic chaplain, Fr. Fabian Flynn. This year, we have another guest poster. Adina Johnson is a Ph.D. student in U.S. History at Baylor University. Her research is on women and religion during World War II. I’m delighted that she was willing to share a few thoughts with the RiAH blog. ~Jonathan Den Hartog

In the midst of World War II, the Seattle Times expressed the distinctiveness and value of a woman’s contribution to the war effort: "Men fight the war with bayonets, long hours at defense jobs, 'leisure' hours at air-raid drills. Women fight the war with stewpans, knitting needles, alarm clocks that go off at 4 o'clock in the morning, rudely awakened babies, unelastic budgets, fast-rising prices." The advertisement suggested a man might receive more glory for his efforts, but “women’s work” was just as important to America’s effort to win the war. For the Times, a woman’s service in the private sphere was as essential, and as patriotic, as a man’s sacrifice in the public sphere.

Iconic images from the American war effort such as Rosie the Riveter, Red Cross nurses, victory gardens, gold stars hanging in windows, and female WASP pilots all convey the importance of a woman’s contribution to the Allied cause, and the righteousness of her doing so no matter the cost. For conservative Protestants, however, the story was more complicated because of deep-seated ideals regarding the value of a woman’s presence within a Christian home. Conservative Protestant periodicals from the war years show that a woman who chose to become a soldier or war-worker held a precarious position within the Christian community. The press attempted to alleviate some of this unease by describing her public roles using the language of domesticity and spirituality, even as her work took her far outside the bounds of traditional Victorian womanhood.

No image would come to symbolize the role of American women during World War II more indelibly than “Rosie the Riveter”. The quintessential “Rosie” was a woman who exemplified patriotic femininity while working in a wartime factory wearing overalls and a bandanna. Indeed, many women entered the work force for the first time during the war, in traditionally masculine jobs. However, both mainstream Americans and conservative Protestants wrestled with the impact of this change. Both voiced concerns for the health of the family, and emphasized the necessity of other wartime roles for women, but the conservative Protestant press could never quite bring itself to fully affirm the idea of a mother or wife working outside the home.

No image would come to symbolize the role of American women during World War II more indelibly than “Rosie the Riveter”. The quintessential “Rosie” was a woman who exemplified patriotic femininity while working in a wartime factory wearing overalls and a bandanna. Indeed, many women entered the work force for the first time during the war, in traditionally masculine jobs. However, both mainstream Americans and conservative Protestants wrestled with the impact of this change. Both voiced concerns for the health of the family, and emphasized the necessity of other wartime roles for women, but the conservative Protestant press could never quite bring itself to fully affirm the idea of a mother or wife working outside the home.The experiences of conservative Protestant women in relation to war work reflect the experiences of American women as a whole. Some entered the work force while others stayed home with their families. Pat Williams, a Southern Baptist woman from West Texas, observed that many women in her church worked at a munitions plant about thirteen miles away, especially those women whose husbands were in the service. She recognized that this was a new phenomenon, “Before then women basically didn’t many of them work outside the home, nurses probably, school teachers, and a few secretaries . . . But most women just stayed home.” Donna M. Panknin Denton, from Waco, Texas, worked two jobs during the war. Her first job was playing the organ or piano for local funerals. Her primary job, though, was working at a war plant that manufactured ammonia and nitric acid. She noted, “Of course, I was in the administrative building,” a comment that revealed her assumption that women wouldn’t work in the factory itself. Most conservative Protestant women were able to navigate the potential conflict between war work and their responsibility as Christian wives and mothers without much trouble.

The conservative Protestant press took a decidedly more critical stance on “Rosie”, their articles focusing on war work’s dangers for families and marriages without directly renouncing it. They were pushing back against the pro-“Rosie” agenda of the secular press and warning conservative women against neglecting their primary duties in the home. A poem published in the Baptist Watchman-Examiner displays the mixed-feelings conservative Protestants felt towards Rosie:

She's swapped her flowered smock for slacks,This poem highlights how emotionally problematic the necessity of women war workers was to conservative Protestants. It never explicitly denounces factory work, and in fact praises the efforts of those creating plane parts. But this was clearly not a desirable occupation for women better suited for housework or child-rearing. Other articles also approached this issue with trepidation, if not outright warnings. An editorial in Banner magazine condemned government propaganda for encouraging women to leave their homes for war work. “The lure of high wages in defense factories has taken thousands of mothers out of their homes and away from their children. War or no war, it is a crime against society and against the institution of the home to urge mothers to abandon their children for the sake of helping win the war.” Conservative Protestants did not mince words when the fate of the family was on the line.

And all her energy and art

Devoted once to kitchen chores

Now goes to form an airplane part.

With strong back and certain touch

She joins the metal skin and beam,

Driving stubborn rivets home

As deftly as she'd sew a seam

Unfalteringly she fashions well

The man-made war birds, swift and fatal,

But building death's a heavy task

For hands best shaped to rock the cradle.

The conservative press never placed the principles of Christian domesticity and piety on the back burner, even during World War II. A Christian “Rosie” could be honorable as long as family and the home always stayed her top priority. The conservative Protestant media differed from the secular media in that Christian authors and editors never wholeheartedly endorsed women in the factories, even as conservative women sought out these roles along with their mainline counterparts.

Comments