Sex in the Pacific

Charles McCrary

This post is the third installment in a series on the Pacific. For previous entries, see parts 1, 2a, and 2b.

The first post in this series ended with a question: What models, topics, and themes might we use to study the Pacific and to incorporate Pacific history into American religious history? Global history is often best told by following one theme—an idea, group, commodity, even an individual—in order to trace the networks of people, things, and capital that create world history. Sidney Mintz’s seminal Sweetness and Power has been a model for food studies and global histories, with its dynamic ability to focus on vast trade networks, labor, and capital, as well as the cultural changes (such as how the British eat dessert) driving and driven by global capitalism. Many others have studied foods in this way: Mark Kurlanksy’s popular histories of cod and salt, as well as forthcoming work from Augustine Sedgewick on coffee and Hi'ilei Hobart on ice. Scholars have studied other commodities and their networks. Gregory Cushman’s Guano and the Opening of the Pacific World, which won last year’s inaugural Jerry Bentley Prize, awarded by the AHA to the best book “dealing with global or world-scale history,” is an outstanding, wide-ranging book that incorporates many subfields and topics (including religious/missions history) while telling its detailed stories. It’s one of the best books I read last year; you should read it. See also Sven Beckert's Empire of Cotton, which recently won the Bancroft Prize.

I want to spend some more time considering broad frameworks (flows, networks, exchange) that might allow for a Pacific– and globally oriented American religious history. One way to get at these issues, and to focus and organize our inquiries, is to think about particular themes and topics. Which subjects might provide us lenses into broad histories that bridge subfields? Capitalism, empire, environment, and the more specific topics associated with them all provide fruitful lenses. Here, working with an “exchange” model, I’ll sketch broadly how an interdisciplinary Pacific history might be told through a particular type of exchange: sex.

European and American contact with Pacific Islanders was frequently sexual. Those voyagers were often surprised and, as stories traveled, more often enticed by the roles that sex played some Polynesian societies, whose mores regarding sexual contact and partners were regulated by codes different from Europeans’. In the Marquesas, for example, Nicholas Thomas has shown, “There was usually a good deal of sexual contact, and voyagers tended to be shocked that girls as young as eight or nine should be involved, and also that husbands should offer their wives, and fathers their daughters.”[1] Sex became a means of exchange. Islander girls and women, almost universally perceived among as beautiful and alluring, took advantage of what both sides saw as favorable exchange rates. In Hawai‘i, Cook’s men traded sexual favors for iron—an extremely valuable commodity, since Polynesians had no metal except that which they could attain by trade with Europeans—receiving sex acts in exchange for as little as, in some cases, a single nail. The women, many of whom also had sex with Europeans for free, considered it quite a bargain.

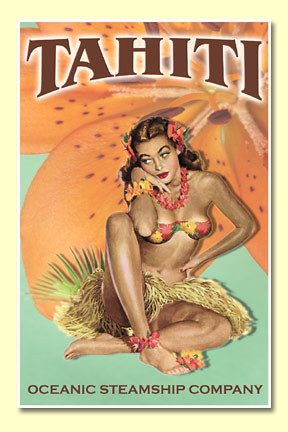

The trope of the beautiful and naturally sexual island girl became a standard of European and American literature.[2] In Typee: A Peep at Polynesian Life (1846), Herman Melville’s narrator, Tommo, observes the Marquesan “nymph” Fayaway: “The easy unstudied graces of a child of nature like this, breathing from infancy an atmosphere of perpetual summer, and nurtured by the simple fruits of the earth; enjoying a perfect freedom from care and anxiety, and removed effectually from all injurious tendencies, strike the eye in a manner which cannot be pourtrayed.”[3] He went on to mention, “Fayaway—I must avow the fact—for the part clung to the primitive and summer garb of Eden. But how becoming the costume!”[4] With descriptions like this, in combination with the Edenic descriptions and depictions of the land and water itself (see, e.g., William Hodges’s paintings from the Cook voyages), it should be no surprise that many European and American explorers, merchants, and whalers joined voyages in hopes of such encounters. The tropes of the sexual island girl would persist into the twentieth century, especially as the Hawaiian “hula girl,” as a way to feminize, exoticize, and domesticate the Pacific, all at once.[5] The image of the islands as “inviting” worked to justify their conquest. As whaling and exploring voyages ceased, the character of the young Nantucketer out for adventure and sexual conquest was replaced with the American sailor.[6]

Not all sexual exchange was consensual, though. Europeans frequently misinterpreted Polynesian codes regarding dress and bodily performance. For example, as Anne Salmond has explain in Aphrodite’s Island, a history of Europeans and Tahitians in which sex plays a central role, “in Tahiti people stripped to the waist in the presence of gods and high chiefs, and a high-ranking stranger was often greeted by a young girl swathed in layers of bark cloth who slowly turned around, unwinding the bark from her body until she stood naked—a ritual presentation with no necessary implication of sexual availability.”[7] Captain Bougainville’s men, who had not seen women in many months, misunderstood the ritual’s meaning, and some of the girls sent to greet the first European ships in Tahitian harbors narrowly escaped (and sometimes did not escape) sexual assault. Not at assaults were simply the results of misunderstandings, of course. A little over a decade later, Captain James Cook would discipline his men for raping women on those same Tahitian beaches.[8]

Consensual or not, sex between Europeans and Islanders had devastating results. Rates of death due to diseases, particularly those sexually transmitted, were extremely high. As Nicholas Thomas notes, the extent of population decline “is highly debatable, indeed this is one of the most controversial topics in public as well as academic argument about the Pacific past.”[9] The debates stem from the fact that there is no reliable data on population before contact. What is clear, though, is that populations declined significantly. In the Marquesas, Thomas’s particular area of expertise, he notes that between 1800 and 1840 the population dropped from at least 35,000 to under 20,000.[10] How much the population had already declined before 1800 is not clear. Some sailors were unaware of the effects of these diseases, but most Islanders and Europeans figured out what was going on; figuring out how to stop it was another, far less successful, matter.

On Cook’s third and final voyage, the one on which he “discovered” the Hawaiian Islands, his crew was riddled with gonorrhea and syphilis after their 1777 summer in Tahiti. Cook demanded that his crew cease sexual contact with Islanders. He threatened his crew with harsh punishment, including flogging (something he did far more often on the third voyage than on the first two, as Gananath Obeyesekere famously emphasized), if they had sex with women. Upon their return to the islands, nine months later, they approached Maui, a considerable distance from Kaua‘i, where they had been earlier in the year. Cook surmised that the people of Maui were indeed of the same people group as those in the western Hawaiian islands. He quickly published an order prohibiting any contact with the islanders. It was already too late, though. He recorded the November 26, 1778 entry in his diary: “Women were also forbid to be admited [sic] into the Ships, but under certain restrictions, but the evil I meant to prevent by this I found had already got amongst them.”[11] The population of the Hawaiian Islands was decimated.

Here I have provided just a few examples of how sex has played a central role in the history and study of the Pacific. Sex is a fruitful topic because it demands attention to the personal interactions and physical exchanges (of fluids, trinkets, diseases, mana) between Islanders and Europeans and Americans. It also provides a window into the Western gaze at the Pacific, and focuses our attention on the interplays between perceptions and reality, showing how real contact could change perceptions, and certain perceptions could encourage or shape contact. Finally, the study of sex allows for simultaneous lenses of varying scope. While we cannot escape the very lived materiality of sexual exchange, the results of these exchanges happened on the largest scale, dramatically changing economies, populations, and cultures.[12] A history of the Pacific—and, I would argue, a more complete history of America—must account for the trade networks and cultural exchange, but also microbes, and take into account all the “deadly processes at work—processes at once social, historical, and epidemiological.”[13]

[7] Anne Salmond, Aphrodite’s Island: The European Discovery of Tahiti (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2009), 19.

[8] Ibid., 277–278.

[9] Nicholas Thomas, Islanders: The Pacific in the Age of Empire (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press), 22.

[10] Ibid., 23.

[11] James Cook, The Journals, ed. Philip Edwads (New York: Penguin, 2003), 593.

[12] See Seth Archer, “Remedial Agents: Missionary Physicians and the Depopulation of Hawai‘i,” Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 79, No. 4 (Nov. 2010) and Archer, “Sharks Upon the Land: Epidemics and Culture in Hawai‘i, 1778–1865” (PhD Diss, University of California–Riverside, 2015).

[13] David Igler, The Great Ocean: Pacific Worlds from Captain Cook to the Gold Rush (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 45. For a brilliant but depressing narrative of disease history in the Pacific, one that keeps the largest and smallest frames working simultaneously, see chapter two, “Disease, Sex, and Indigenous Depopulation” (43–71). This chapter is adapted from an earlier article in The American Historical Review, available in PDF form here.

European and American contact with Pacific Islanders was frequently sexual. Those voyagers were often surprised and, as stories traveled, more often enticed by the roles that sex played some Polynesian societies, whose mores regarding sexual contact and partners were regulated by codes different from Europeans’. In the Marquesas, for example, Nicholas Thomas has shown, “There was usually a good deal of sexual contact, and voyagers tended to be shocked that girls as young as eight or nine should be involved, and also that husbands should offer their wives, and fathers their daughters.”[1] Sex became a means of exchange. Islander girls and women, almost universally perceived among as beautiful and alluring, took advantage of what both sides saw as favorable exchange rates. In Hawai‘i, Cook’s men traded sexual favors for iron—an extremely valuable commodity, since Polynesians had no metal except that which they could attain by trade with Europeans—receiving sex acts in exchange for as little as, in some cases, a single nail. The women, many of whom also had sex with Europeans for free, considered it quite a bargain.

|

| Fayaway, illustration from a 1892 edition of Typee |

The trope of the beautiful and naturally sexual island girl became a standard of European and American literature.[2] In Typee: A Peep at Polynesian Life (1846), Herman Melville’s narrator, Tommo, observes the Marquesan “nymph” Fayaway: “The easy unstudied graces of a child of nature like this, breathing from infancy an atmosphere of perpetual summer, and nurtured by the simple fruits of the earth; enjoying a perfect freedom from care and anxiety, and removed effectually from all injurious tendencies, strike the eye in a manner which cannot be pourtrayed.”[3] He went on to mention, “Fayaway—I must avow the fact—for the part clung to the primitive and summer garb of Eden. But how becoming the costume!”[4] With descriptions like this, in combination with the Edenic descriptions and depictions of the land and water itself (see, e.g., William Hodges’s paintings from the Cook voyages), it should be no surprise that many European and American explorers, merchants, and whalers joined voyages in hopes of such encounters. The tropes of the sexual island girl would persist into the twentieth century, especially as the Hawaiian “hula girl,” as a way to feminize, exoticize, and domesticate the Pacific, all at once.[5] The image of the islands as “inviting” worked to justify their conquest. As whaling and exploring voyages ceased, the character of the young Nantucketer out for adventure and sexual conquest was replaced with the American sailor.[6]

Not all sexual exchange was consensual, though. Europeans frequently misinterpreted Polynesian codes regarding dress and bodily performance. For example, as Anne Salmond has explain in Aphrodite’s Island, a history of Europeans and Tahitians in which sex plays a central role, “in Tahiti people stripped to the waist in the presence of gods and high chiefs, and a high-ranking stranger was often greeted by a young girl swathed in layers of bark cloth who slowly turned around, unwinding the bark from her body until she stood naked—a ritual presentation with no necessary implication of sexual availability.”[7] Captain Bougainville’s men, who had not seen women in many months, misunderstood the ritual’s meaning, and some of the girls sent to greet the first European ships in Tahitian harbors narrowly escaped (and sometimes did not escape) sexual assault. Not at assaults were simply the results of misunderstandings, of course. A little over a decade later, Captain James Cook would discipline his men for raping women on those same Tahitian beaches.[8]

Consensual or not, sex between Europeans and Islanders had devastating results. Rates of death due to diseases, particularly those sexually transmitted, were extremely high. As Nicholas Thomas notes, the extent of population decline “is highly debatable, indeed this is one of the most controversial topics in public as well as academic argument about the Pacific past.”[9] The debates stem from the fact that there is no reliable data on population before contact. What is clear, though, is that populations declined significantly. In the Marquesas, Thomas’s particular area of expertise, he notes that between 1800 and 1840 the population dropped from at least 35,000 to under 20,000.[10] How much the population had already declined before 1800 is not clear. Some sailors were unaware of the effects of these diseases, but most Islanders and Europeans figured out what was going on; figuring out how to stop it was another, far less successful, matter.

On Cook’s third and final voyage, the one on which he “discovered” the Hawaiian Islands, his crew was riddled with gonorrhea and syphilis after their 1777 summer in Tahiti. Cook demanded that his crew cease sexual contact with Islanders. He threatened his crew with harsh punishment, including flogging (something he did far more often on the third voyage than on the first two, as Gananath Obeyesekere famously emphasized), if they had sex with women. Upon their return to the islands, nine months later, they approached Maui, a considerable distance from Kaua‘i, where they had been earlier in the year. Cook surmised that the people of Maui were indeed of the same people group as those in the western Hawaiian islands. He quickly published an order prohibiting any contact with the islanders. It was already too late, though. He recorded the November 26, 1778 entry in his diary: “Women were also forbid to be admited [sic] into the Ships, but under certain restrictions, but the evil I meant to prevent by this I found had already got amongst them.”[11] The population of the Hawaiian Islands was decimated.

Here I have provided just a few examples of how sex has played a central role in the history and study of the Pacific. Sex is a fruitful topic because it demands attention to the personal interactions and physical exchanges (of fluids, trinkets, diseases, mana) between Islanders and Europeans and Americans. It also provides a window into the Western gaze at the Pacific, and focuses our attention on the interplays between perceptions and reality, showing how real contact could change perceptions, and certain perceptions could encourage or shape contact. Finally, the study of sex allows for simultaneous lenses of varying scope. While we cannot escape the very lived materiality of sexual exchange, the results of these exchanges happened on the largest scale, dramatically changing economies, populations, and cultures.[12] A history of the Pacific—and, I would argue, a more complete history of America—must account for the trade networks and cultural exchange, but also microbes, and take into account all the “deadly processes at work—processes at once social, historical, and epidemiological.”[13]

----------------

[1] Nicholas Thomas, Entangled Objects: Exchange, Material Culture, and Colonialism in the Pacific (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991), 94.

[2] See Patty O’Brien, The Pacific Muse: Exotic Femininity and the Colonial Pacific (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2006).

[3] Herman Melville, Typee; A Peep at Polynesian Life (New York: The Library of America, 1982 [orig. 1846]), 106.

[4] Ibid., 107.

[5] See Adria L. Imada, Aloha America: Hula Circuits Through U.S. Empire (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012).

[6] See Rob Wilson, Reimagining the American Pacific: From South Pacific to Bamboo Ridge and Beyond (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2000). See also Gary Y. Okihiro, Island World: A History of Hawai‘i and the United States (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2008), 188–195.

[1] Nicholas Thomas, Entangled Objects: Exchange, Material Culture, and Colonialism in the Pacific (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991), 94.

[2] See Patty O’Brien, The Pacific Muse: Exotic Femininity and the Colonial Pacific (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2006).

[3] Herman Melville, Typee; A Peep at Polynesian Life (New York: The Library of America, 1982 [orig. 1846]), 106.

[4] Ibid., 107.

[5] See Adria L. Imada, Aloha America: Hula Circuits Through U.S. Empire (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012).

[6] See Rob Wilson, Reimagining the American Pacific: From South Pacific to Bamboo Ridge and Beyond (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2000). See also Gary Y. Okihiro, Island World: A History of Hawai‘i and the United States (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2008), 188–195.

[7] Anne Salmond, Aphrodite’s Island: The European Discovery of Tahiti (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2009), 19.

[8] Ibid., 277–278.

[9] Nicholas Thomas, Islanders: The Pacific in the Age of Empire (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press), 22.

[10] Ibid., 23.

[11] James Cook, The Journals, ed. Philip Edwads (New York: Penguin, 2003), 593.

[12] See Seth Archer, “Remedial Agents: Missionary Physicians and the Depopulation of Hawai‘i,” Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 79, No. 4 (Nov. 2010) and Archer, “Sharks Upon the Land: Epidemics and Culture in Hawai‘i, 1778–1865” (PhD Diss, University of California–Riverside, 2015).

[13] David Igler, The Great Ocean: Pacific Worlds from Captain Cook to the Gold Rush (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 45. For a brilliant but depressing narrative of disease history in the Pacific, one that keeps the largest and smallest frames working simultaneously, see chapter two, “Disease, Sex, and Indigenous Depopulation” (43–71). This chapter is adapted from an earlier article in The American Historical Review, available in PDF form here.

Comments