Religious Freedom And U.S. Foreign Policy Roundtable

Lauren Turek

Recent footage from the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL or ISIS) showing the brutal executions of imprisoned Ethiopian and Egyptian Christians in Libya has reignited calls to the U.S. government to take action to protect religious minorities abroad. Among those who have urged Congress and President Obama to act, retired congressman Frank Wolf has been particularly vocal on the need to use the levers of American foreign policy to defend religious freedom throughout the world. Wolf took a leading role in passing international religious freedom legislation in the late 1990s. Though the bill he introduced with Senator Arlen Specter in 1997 failed, in part due to concerns that it prioritized Christians over other persecuted religious groups, he rallied to support a compromise bill that Congressman Don Nickles and Senator Joseph Lieberman introduced in 1998. That legislation passed, and President Clinton signed the International Religious Freedom Act (IRFA) into law on October 27, 1998. The IRFA established the Office of International Religious Freedom at the State Department as well as an independent Commission on International Religious Freedom and a special advisor to the National Security Council. Representative Christoper Smith, who has long served on the House Foreign Affairs committee and lent strong support to the Wolf-Specter and IRFA bills in the late 1990s, recently introduced the Frank R. Wolf International Religious Freedom Act of 2015 to update the 1998 IRFA; Smith referenced ISIL’s attacks on Christians in Libya as a motivating factor in his decision to introduce this legislation.

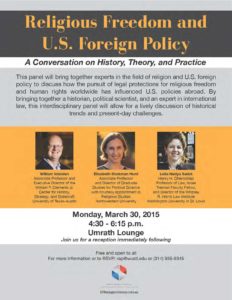

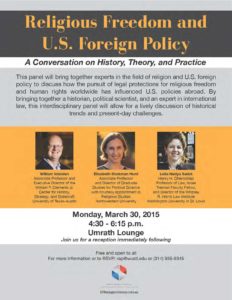

Last month, the John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics at Washington University in St. Louis hosted an interdisciplinary roundtable discussion on international religious freedom and U.S. foreign policy, which reflected on the efficacy of the 1998 IRFA and how incorporating protections for religious freedom into the matrix of foreign policy making has shaped the way that the United States engages with other states. The panel, "Religious Freedom And U.S. Foreign Policy: A Conversation On History, Theory, And Practice," brought together three scholars of history, politics, and international law: Dr. William Inboden, the Executive Director of the William P. Clements, Jr. Center for History, Strategy, and Statecraft at the University of Texas-Austin (who, among many other things, previously worked at the Department of State as a Member of the Policy Planning Staff and as a Special Advisor in the Office of International Religious Freedom) and author of Religion and American Foreign Policy, 1945-1960: The Soul of Containment; Dr. Elizabeth Hurd, Associate Professor of Political Science with a courtesy appointment in Religious Studies at Northwestern University, and author of Beyond Religious Freedom: The New Global Politics of Religion; and Professor Leila Sadat, an internationally recognized human rights expert specializing in international criminal law and justice who is the Henry H. Oberschelp Professor of Law at Washington University School of Law and director of the Whitney R. Harris World Law Institute and Special Adviser on Crimes Against Humanity at the International Criminal Court. Professor Sadat also served on the U. S. Commission for International Religious Freedom from 2001-2003.

Last month, the John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics at Washington University in St. Louis hosted an interdisciplinary roundtable discussion on international religious freedom and U.S. foreign policy, which reflected on the efficacy of the 1998 IRFA and how incorporating protections for religious freedom into the matrix of foreign policy making has shaped the way that the United States engages with other states. The panel, "Religious Freedom And U.S. Foreign Policy: A Conversation On History, Theory, And Practice," brought together three scholars of history, politics, and international law: Dr. William Inboden, the Executive Director of the William P. Clements, Jr. Center for History, Strategy, and Statecraft at the University of Texas-Austin (who, among many other things, previously worked at the Department of State as a Member of the Policy Planning Staff and as a Special Advisor in the Office of International Religious Freedom) and author of Religion and American Foreign Policy, 1945-1960: The Soul of Containment; Dr. Elizabeth Hurd, Associate Professor of Political Science with a courtesy appointment in Religious Studies at Northwestern University, and author of Beyond Religious Freedom: The New Global Politics of Religion; and Professor Leila Sadat, an internationally recognized human rights expert specializing in international criminal law and justice who is the Henry H. Oberschelp Professor of Law at Washington University School of Law and director of the Whitney R. Harris World Law Institute and Special Adviser on Crimes Against Humanity at the International Criminal Court. Professor Sadat also served on the U. S. Commission for International Religious Freedom from 2001-2003.

The panelists drew on their academic scholarship and, in some cases, their policy experience, to discuss the relationship between international human rights, religious freedom, and U.S. foreign policy. Dr. Inboden provided a historical overview of the evolution of concerns about religious persecution abroad and how these concerns gradually came to have greater purchase in Congress and on policy makers over the course of the twentieth century. He also dispensed with the notion that evangelical Christian activists spearheaded the IRFA as a means to promote missionary work, noting the diversity of the coalition of religious and secular human rights organizations that mobilized to support the bill. Inboden argued that the campaign to pass the IRFA reflected a desire to incorporate core American ideals into U.S. foreign policy, rather than an effort to remake the world in the image of the United States. He noted that the IRFA had not proved particularly effective in promoting religious freedom abroad however.

In addition to Dr. Inboden’s overview and his reflections on his time working in the State Department, the panelists thought through a number of key questions on the influence of the IRFA on U.S. human rights policies more broadly and the changing meaning of the concepts of human rights and religious freedom over time. Dr. Hurd discussed religious freedom as an abstract norm in international relations, noting the challenges that political leaders face in interpreting the meaning of religious freedom, as well as the definitions of religion and religious groups. Her remarks raised some of the major questions that scholars of religion and religious history grapple with in their work—namely, what is religion?—and she offered fascinating insights into the question of how policymakers have defined religion in the context of foreign affairs. Finally, Professor Sadat discussed the practical workings of the IRFA, noting the benefits and drawbacks of singling out religious liberty as a core freedom in need of special protections. Her experience as an international human rights lawyer and former member of the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom offered unparalleled insight into how grassroots activism, academic scholarship, and legal theory interact at the highest levels of international law.

As with any good scholarly discussion, the panel raised many more questions than answers. After all, how should we define religious groups and religion when formulating legislation to protect human rights? Historically, how effective has U.S. legislation on international religious freedom been in reducing religious persecution abroad? How have other nations perceived these policies? Are policies that seek to promote American constitutional ideals abroad a form of cultural imperialism?

As concern about persecution and deadly violence against religious minorities throughout the world escalates, many of the questions that Inboden, Hurd, Sadat, and the Danforth Center audience raised should and likely will also come up in future congressional debates about U.S. legislation on international religious freedom.

A full video of the roundtable is available below and at the John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics website.

Recent footage from the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL or ISIS) showing the brutal executions of imprisoned Ethiopian and Egyptian Christians in Libya has reignited calls to the U.S. government to take action to protect religious minorities abroad. Among those who have urged Congress and President Obama to act, retired congressman Frank Wolf has been particularly vocal on the need to use the levers of American foreign policy to defend religious freedom throughout the world. Wolf took a leading role in passing international religious freedom legislation in the late 1990s. Though the bill he introduced with Senator Arlen Specter in 1997 failed, in part due to concerns that it prioritized Christians over other persecuted religious groups, he rallied to support a compromise bill that Congressman Don Nickles and Senator Joseph Lieberman introduced in 1998. That legislation passed, and President Clinton signed the International Religious Freedom Act (IRFA) into law on October 27, 1998. The IRFA established the Office of International Religious Freedom at the State Department as well as an independent Commission on International Religious Freedom and a special advisor to the National Security Council. Representative Christoper Smith, who has long served on the House Foreign Affairs committee and lent strong support to the Wolf-Specter and IRFA bills in the late 1990s, recently introduced the Frank R. Wolf International Religious Freedom Act of 2015 to update the 1998 IRFA; Smith referenced ISIL’s attacks on Christians in Libya as a motivating factor in his decision to introduce this legislation.

Last month, the John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics at Washington University in St. Louis hosted an interdisciplinary roundtable discussion on international religious freedom and U.S. foreign policy, which reflected on the efficacy of the 1998 IRFA and how incorporating protections for religious freedom into the matrix of foreign policy making has shaped the way that the United States engages with other states. The panel, "Religious Freedom And U.S. Foreign Policy: A Conversation On History, Theory, And Practice," brought together three scholars of history, politics, and international law: Dr. William Inboden, the Executive Director of the William P. Clements, Jr. Center for History, Strategy, and Statecraft at the University of Texas-Austin (who, among many other things, previously worked at the Department of State as a Member of the Policy Planning Staff and as a Special Advisor in the Office of International Religious Freedom) and author of Religion and American Foreign Policy, 1945-1960: The Soul of Containment; Dr. Elizabeth Hurd, Associate Professor of Political Science with a courtesy appointment in Religious Studies at Northwestern University, and author of Beyond Religious Freedom: The New Global Politics of Religion; and Professor Leila Sadat, an internationally recognized human rights expert specializing in international criminal law and justice who is the Henry H. Oberschelp Professor of Law at Washington University School of Law and director of the Whitney R. Harris World Law Institute and Special Adviser on Crimes Against Humanity at the International Criminal Court. Professor Sadat also served on the U. S. Commission for International Religious Freedom from 2001-2003.

Last month, the John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics at Washington University in St. Louis hosted an interdisciplinary roundtable discussion on international religious freedom and U.S. foreign policy, which reflected on the efficacy of the 1998 IRFA and how incorporating protections for religious freedom into the matrix of foreign policy making has shaped the way that the United States engages with other states. The panel, "Religious Freedom And U.S. Foreign Policy: A Conversation On History, Theory, And Practice," brought together three scholars of history, politics, and international law: Dr. William Inboden, the Executive Director of the William P. Clements, Jr. Center for History, Strategy, and Statecraft at the University of Texas-Austin (who, among many other things, previously worked at the Department of State as a Member of the Policy Planning Staff and as a Special Advisor in the Office of International Religious Freedom) and author of Religion and American Foreign Policy, 1945-1960: The Soul of Containment; Dr. Elizabeth Hurd, Associate Professor of Political Science with a courtesy appointment in Religious Studies at Northwestern University, and author of Beyond Religious Freedom: The New Global Politics of Religion; and Professor Leila Sadat, an internationally recognized human rights expert specializing in international criminal law and justice who is the Henry H. Oberschelp Professor of Law at Washington University School of Law and director of the Whitney R. Harris World Law Institute and Special Adviser on Crimes Against Humanity at the International Criminal Court. Professor Sadat also served on the U. S. Commission for International Religious Freedom from 2001-2003.The panelists drew on their academic scholarship and, in some cases, their policy experience, to discuss the relationship between international human rights, religious freedom, and U.S. foreign policy. Dr. Inboden provided a historical overview of the evolution of concerns about religious persecution abroad and how these concerns gradually came to have greater purchase in Congress and on policy makers over the course of the twentieth century. He also dispensed with the notion that evangelical Christian activists spearheaded the IRFA as a means to promote missionary work, noting the diversity of the coalition of religious and secular human rights organizations that mobilized to support the bill. Inboden argued that the campaign to pass the IRFA reflected a desire to incorporate core American ideals into U.S. foreign policy, rather than an effort to remake the world in the image of the United States. He noted that the IRFA had not proved particularly effective in promoting religious freedom abroad however.

In addition to Dr. Inboden’s overview and his reflections on his time working in the State Department, the panelists thought through a number of key questions on the influence of the IRFA on U.S. human rights policies more broadly and the changing meaning of the concepts of human rights and religious freedom over time. Dr. Hurd discussed religious freedom as an abstract norm in international relations, noting the challenges that political leaders face in interpreting the meaning of religious freedom, as well as the definitions of religion and religious groups. Her remarks raised some of the major questions that scholars of religion and religious history grapple with in their work—namely, what is religion?—and she offered fascinating insights into the question of how policymakers have defined religion in the context of foreign affairs. Finally, Professor Sadat discussed the practical workings of the IRFA, noting the benefits and drawbacks of singling out religious liberty as a core freedom in need of special protections. Her experience as an international human rights lawyer and former member of the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom offered unparalleled insight into how grassroots activism, academic scholarship, and legal theory interact at the highest levels of international law.

As with any good scholarly discussion, the panel raised many more questions than answers. After all, how should we define religious groups and religion when formulating legislation to protect human rights? Historically, how effective has U.S. legislation on international religious freedom been in reducing religious persecution abroad? How have other nations perceived these policies? Are policies that seek to promote American constitutional ideals abroad a form of cultural imperialism?

As concern about persecution and deadly violence against religious minorities throughout the world escalates, many of the questions that Inboden, Hurd, Sadat, and the Danforth Center audience raised should and likely will also come up in future congressional debates about U.S. legislation on international religious freedom.

A full video of the roundtable is available below and at the John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics website.

Comments