Ask the Southern Baptist Convention and Robert Dale Owen? Or advice on the best age for marriage

Carol Faulkner

Last month, a NPR story about the Southern Baptist Convention's "soft push" for early marriages caught my attention. My mother always told me not to marry until age 30, which says a lot about her political and philosophical differences from leaders of the Southern Baptist Convention. When I reached that age as a single woman, however, she began to get nervous. Still, my mother was on to something. Studies show that college-educated women who delay marriage do better financially than women who marry at a younger age. The Southern Baptist Convention's new campaign grows from their awareness of the rising marriage age (as of 2011, the average age of marriage for women was 26.5 years, for men, 28.7), as well as the denomination's interest in discouraging premarital sex. The NPR story quotes Andrew Walker, who leads SBC efforts on early marriages, explaining the rationale: "The reality is, starting at the age of 12, 13, boys and men, growing up into maturity, are hardwired for something that God gave us a desire for and an outlet for.... And so to suppress that becomes more difficult the older you get." Though there is a lot to say about this quote, I will focus on how it echoes the marriage advice of antebellum reformers. Aside from shared disapproval of premarital sex, these reformers had little in common with antebellum or modern evangelicals. Their advice on the appropriate age of marriage reveals their contradictory attempts to address sexual inequality in nineteenth-century America.

Perhaps the best-known of these nineteenth-century writers was socialist (and later spiritualist) Robert Dale Owen, whose book Moral Physiology famously promoted the use of birth control among married couples.* Owen shared Malthus's concern with population growth, but he also believed contraception enabled couples to achieve economic stability and, more importantly, personal happiness. Owen posited that, "the families of the married often increase beyond what a regard for the young beings coming into existence or the happiness of those who give them birth, would dictate." He wrote in opposition to "orthodox" clergy who advocated later marriages as a means of birth control. Instead, Owen argued that early marriages would solve a number of social problems, including onanism (masturbation), seduction, and prostitution, because "all men will marry while young" if they had the ability to limit their children. Owen saw sexual fulfillment as essential to marriage. In his view, early marriages, when combined with birth control, would be "salutory, moral, and civilizing" for both men and women.

Though Owen did not pinpoint a precise age (the Southern Baptist Convention is also keeping it vague), phrenologists were more specific. Due to their investment in physical explanations for human behavior, phrenologists were anathema to many religious Americans, but they shared a commitment to marriage as a monogamous and sacred institution. The Fowler brothers, the best known American phrenologists, believed the democratic study of phrenology would contribute to marital harmony, as specific "organs" showed individual capacity for love and marriage. The Fowlers believed in true love, and they discouraged any flirtation, and certainly any romance, before finding "the one." Flirting, reading novels, and going to the theater, they asserted, inflamed the love organs of the head. Yet they advised men and women to wait for marriage, arguing that marriage required education, maturity, and phrenological self-knowledge. Lorenzo Fowler recommended that women marry at age 20, and men at age 25. His brother Orson suggested that marriage should be postponed until between the ages of 20 and 30, and couples should court for 3 to 5 years in preparation for marriage. The Fowlers' advice had the benefit of demonstrating their reformist interest in sexual self-control without challenging standard nineteenth-century marriage practices.

These two examples show why nineteenth-century reformers worried about the best age for marriage. Similar to the SBC, these writers assumed fundamental sexual differences between men and women, but their goal was to resolve these differences in order to improve marriage. Unlike the SBC, Owen's advocacy of early marriages came from his interest in equality. He viewed birth control as a way to counter the sexual double standard and create mutual, pleasurable relationships between men and women. In contrast, phrenologists urged couples to wait, viewing sexual restraint as key to marital bliss. Though phrenologists' secular justifications differ on the surface, they anticipated the concerns of the SBC, defining premarital sex as dangerous to the individual and a threat to marriage itself. While the SBC's Andrew Walker sees marriage as a sexual outlet for men, the Fowlers had faith in the male capacity for self-control. For the Fowlers, as for many nineteenth-century marriage reformers, continence was the key to egalitarian marriages.

These two examples show why nineteenth-century reformers worried about the best age for marriage. Similar to the SBC, these writers assumed fundamental sexual differences between men and women, but their goal was to resolve these differences in order to improve marriage. Unlike the SBC, Owen's advocacy of early marriages came from his interest in equality. He viewed birth control as a way to counter the sexual double standard and create mutual, pleasurable relationships between men and women. In contrast, phrenologists urged couples to wait, viewing sexual restraint as key to marital bliss. Though phrenologists' secular justifications differ on the surface, they anticipated the concerns of the SBC, defining premarital sex as dangerous to the individual and a threat to marriage itself. While the SBC's Andrew Walker sees marriage as a sexual outlet for men, the Fowlers had faith in the male capacity for self-control. For the Fowlers, as for many nineteenth-century marriage reformers, continence was the key to egalitarian marriages.

*Owen's controversial book included information about various ways to prevent pregnancy, including condoms, sponges, and withdrawal.

Last month, a NPR story about the Southern Baptist Convention's "soft push" for early marriages caught my attention. My mother always told me not to marry until age 30, which says a lot about her political and philosophical differences from leaders of the Southern Baptist Convention. When I reached that age as a single woman, however, she began to get nervous. Still, my mother was on to something. Studies show that college-educated women who delay marriage do better financially than women who marry at a younger age. The Southern Baptist Convention's new campaign grows from their awareness of the rising marriage age (as of 2011, the average age of marriage for women was 26.5 years, for men, 28.7), as well as the denomination's interest in discouraging premarital sex. The NPR story quotes Andrew Walker, who leads SBC efforts on early marriages, explaining the rationale: "The reality is, starting at the age of 12, 13, boys and men, growing up into maturity, are hardwired for something that God gave us a desire for and an outlet for.... And so to suppress that becomes more difficult the older you get." Though there is a lot to say about this quote, I will focus on how it echoes the marriage advice of antebellum reformers. Aside from shared disapproval of premarital sex, these reformers had little in common with antebellum or modern evangelicals. Their advice on the appropriate age of marriage reveals their contradictory attempts to address sexual inequality in nineteenth-century America.

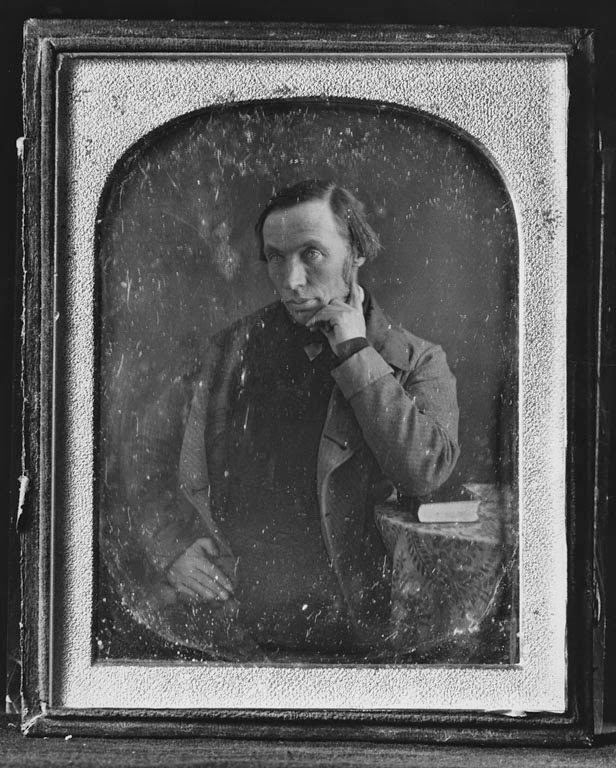

|

| Robert Dale Owen |

Perhaps the best-known of these nineteenth-century writers was socialist (and later spiritualist) Robert Dale Owen, whose book Moral Physiology famously promoted the use of birth control among married couples.* Owen shared Malthus's concern with population growth, but he also believed contraception enabled couples to achieve economic stability and, more importantly, personal happiness. Owen posited that, "the families of the married often increase beyond what a regard for the young beings coming into existence or the happiness of those who give them birth, would dictate." He wrote in opposition to "orthodox" clergy who advocated later marriages as a means of birth control. Instead, Owen argued that early marriages would solve a number of social problems, including onanism (masturbation), seduction, and prostitution, because "all men will marry while young" if they had the ability to limit their children. Owen saw sexual fulfillment as essential to marriage. In his view, early marriages, when combined with birth control, would be "salutory, moral, and civilizing" for both men and women.

Though Owen did not pinpoint a precise age (the Southern Baptist Convention is also keeping it vague), phrenologists were more specific. Due to their investment in physical explanations for human behavior, phrenologists were anathema to many religious Americans, but they shared a commitment to marriage as a monogamous and sacred institution. The Fowler brothers, the best known American phrenologists, believed the democratic study of phrenology would contribute to marital harmony, as specific "organs" showed individual capacity for love and marriage. The Fowlers believed in true love, and they discouraged any flirtation, and certainly any romance, before finding "the one." Flirting, reading novels, and going to the theater, they asserted, inflamed the love organs of the head. Yet they advised men and women to wait for marriage, arguing that marriage required education, maturity, and phrenological self-knowledge. Lorenzo Fowler recommended that women marry at age 20, and men at age 25. His brother Orson suggested that marriage should be postponed until between the ages of 20 and 30, and couples should court for 3 to 5 years in preparation for marriage. The Fowlers' advice had the benefit of demonstrating their reformist interest in sexual self-control without challenging standard nineteenth-century marriage practices.

These two examples show why nineteenth-century reformers worried about the best age for marriage. Similar to the SBC, these writers assumed fundamental sexual differences between men and women, but their goal was to resolve these differences in order to improve marriage. Unlike the SBC, Owen's advocacy of early marriages came from his interest in equality. He viewed birth control as a way to counter the sexual double standard and create mutual, pleasurable relationships between men and women. In contrast, phrenologists urged couples to wait, viewing sexual restraint as key to marital bliss. Though phrenologists' secular justifications differ on the surface, they anticipated the concerns of the SBC, defining premarital sex as dangerous to the individual and a threat to marriage itself. While the SBC's Andrew Walker sees marriage as a sexual outlet for men, the Fowlers had faith in the male capacity for self-control. For the Fowlers, as for many nineteenth-century marriage reformers, continence was the key to egalitarian marriages.

These two examples show why nineteenth-century reformers worried about the best age for marriage. Similar to the SBC, these writers assumed fundamental sexual differences between men and women, but their goal was to resolve these differences in order to improve marriage. Unlike the SBC, Owen's advocacy of early marriages came from his interest in equality. He viewed birth control as a way to counter the sexual double standard and create mutual, pleasurable relationships between men and women. In contrast, phrenologists urged couples to wait, viewing sexual restraint as key to marital bliss. Though phrenologists' secular justifications differ on the surface, they anticipated the concerns of the SBC, defining premarital sex as dangerous to the individual and a threat to marriage itself. While the SBC's Andrew Walker sees marriage as a sexual outlet for men, the Fowlers had faith in the male capacity for self-control. For the Fowlers, as for many nineteenth-century marriage reformers, continence was the key to egalitarian marriages. *Owen's controversial book included information about various ways to prevent pregnancy, including condoms, sponges, and withdrawal.

Comments