Evangelicals and the Business of One Nation Under God

The following is Darren Grem's review of

Kevin Kruse's best-selling new book, One

Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America.

You can find Mike Graziano's earlier review of Kruse's work here.

Darren E. Grem is Assistant Professor of History and Southern Studies at

the University of Mississippi. His first book, Corporate Revivals: Big

Business and the Shaping of the Evangelical Right, is forthcoming with Oxford

University Press.

Darren Grem

“A nation with the soul of a church.” We

all know the quip. G.K. Chesterton, right? He was wrestling with

the question “What is America?” Here’s what else he had to say, from his

1922 book What I Saw in America:

America is the only

nation in the world that is founded on a creed. That creed is set forth

with dogmatic and even theological lucidity in The Declaration of Independence.

. . . It enunciates that all men are equal in their claim to justice and that

governments exist to given them their justice, and that their authority

is for that reason just. It certainly does condemn anarchism, and it does

also by inference condemn atheism, since it clearly names the Creator as the

ultimate authority from which these equal rights are derived.

Chesterton’s reading of religious meaning into a

foundational document like the Declaration of Independence is the kind of

striving that Kevin M. Kruse’s One Nation Under God historicizes.

According to Kruse, this narrative—that America is a “God blessed” or even “Christian”

nation bestowing equal rights and religious freedom on its citizens and

others—is of recent vintage, and corporate Americans played a key role in

popularizing it after World War II. I won’t rehash Mike Graziano's fine

review for this site. But I would like to consider where Kruse’s book

fits into the series of recent books that consider the role of businessmen and

corporate America in constructing religious categories and narratives in modern

American history. Then, I will suggest how Kruse’s book also reaffirms

some problems and shortcomings in the present historiography and where we might

go next in writing the corporation into our understanding of the modern

religious past.

A number of

scholars have noted the involvement of corporate interests in underwriting

postwar organizations or individuals who trumpeted the notion of a “Christian

America.” Kim Phillips-Fein did so intermittently in Invisible

Hands, primarily by mentioning the economic philosophies at the heart of

tacitly religious organizations like Spiritual Mobilization or the Christian

Freedom Foundation, among others. Bethany Moreton’s To Serve God

and Wal-Mart did not focus on the idea of “Christian America”

specifically, but it certainly detailed how a corporation could affirm narratives

of a God-blessed past to reaffirm expectations for a God-blessed neoliberal

future. Similarly, the businessmen in Darren Dochuk’s From Bible

Belt to Sunbelt who underwrote—in part—the “grassroots” activism of

the earliest evangelical right in southern California held to a sense of

American exceptionalism, which reaffirmed both their laudations of

disestablishment and deregulation. Other scholars have been more thorough

in detailing how narratives of “Christian” national genesis and religious nationalism

intersected with business interests at mid-century. For instance,

Jonathan Herzog’s book on the “spiritual-industrial” complex revealed the

corporate fingerprints of many business leaders, as did certain parts of Wendy

Wall’s book on the businessmen and special interests behind “the politics of

consensus” in the immediate postwar era. There are not many businessmen

in Kevin Schultz’s Tri-Faith America, but the consensus motif is

there, historicized and shown to be a product of multiple, often competing,

special interests and civic groups. All of these books delve into

“religious nationalism” in some form or fashion, and several provide

mini-business histories of corporate America’s interest in creating a

“Christian America,” or “Judeo-Christian America,” or a sense of “Christian

Americanism” where citizenship accorded with—to paraphrase William Lee Miller—a

very sincere belief in a very vague faith. Or, to riff from Chesterton,

that the nation’s government and body politic had a soul of a church.

Kruse is closest to

Herzog and Wall’s books in providing a top-down or middle-down story of postwar

Christian Americanism. Kruse differs from Herzog and Wall in that he

downplays the importance of the warfare state or Cold War in forming what he calls

a “religious nationalism” of “Christian America.” I was curious about

Kruse’s meaning of “religious nationalism,” and I combed the book to see if he

ever refers to this idea and practice as “civil religion,” which I do not

believe he does. Instead, he uses the terms “public religion” or “public

religious expression” as synonyms for “religious nationalism” and “Christian

Americanism” in One Nation Under God, especially in the second half

where the political debates over issues of church and state take precedence.

I can’t honestly articulate what Kruse sees as the difference between “public

religion” and “religious nationalism” or how either are not “civil religion,”

but Kruse seems to be saying that the former is a category of religious experience

that is not or can’t be captured by the older—some may say worn out or

problematic—term “civil religion.”

In any case, he is

certainly saying that our sense of the nation having a church-like “soul”

(meaning that its government is somehow founded on “Christian” sensibilities

and values) is a new thing. Kruse only intermittently takes us backwards

in time to before the 1930s to support his assertion that “America’s religious

identity has its roots not in the foreign policy panic of the 1950s but rather

in the domestic politics of the 1930s and 1940s.” (xiv) I am not a

nineteenth century historian, and I will leave it to my colleagues in that

field to confirm or critique Kruse’s argument on this point. But my sense

is that a Christian religious nationalism, if not quite articulated as an

origins myth, appeared in World War I, during the missionary campaigns of

American imperialism, in the competing regional “civil religions” of the

postbellum era, and in a variety of other venues and places during the Gilded

Age. Thus, it seems less right to say that corporate Americans “invented”

Christian America in the 1930s and 1940s and more right to say they invented a

certain vision of “Christian America” attentive to the context of the late

interwar and early postwar period.

When read in that

way, I find Kruse’s argument thought-provoking, particularly his thesis that

the New Deal, not the Cold War, kick-started corporate pushes for “Christian

libertarianism” (yet another concept that overlaps in Kruse’s book with “public

religion” and “religious nationalism,” primarily because “freedom of religion”

proved a handy slogan for corporate interests pursuing an unraveling of the New

Deal regulatory state). In the 1950s, Americans consumed the

“Christian America” motif that corporate America and Hollywood prepared for

them (Kruse’s understanding of Cecil DeMille’s The Ten Commandments as

“religious” business and brand is fascinating). Then, with the pump

primed in the age of Eisenhower, Americans fought over the terms and conditions

of “Christian America” in the 1960s and 1970s, an irony given that

religio-nationalist practices and “religious rights” language mostly came out

of business meetings and the halls of power in D.C. only a few years

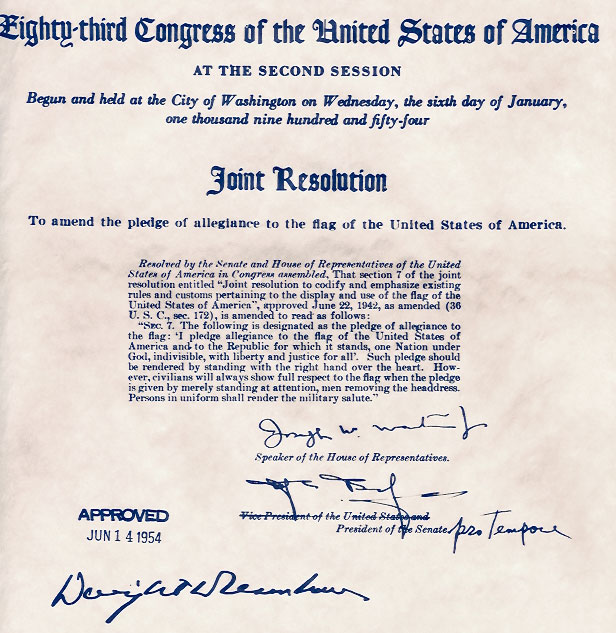

before. Such fights—over school prayer, over public recitation of the

Pledge of Allegiance, over the discourse “One Nation Under God,” over saluting

the flag—defined the cultural politics of liberals and conservatives in the

run-up to “rise” of the New Right, who certainly combined big money and single

issue politics over school prayer or flag reverence with particular aplomb and

fervor. The result was a nation divided under God, although still defined

by a politics of religious nationalism literally “incorporated” a generation

before.

Historiographically

speaking, when Kruse is examining how big business helped make an anti-New

Deal

“Christian Americanism” in the 1930s and 1940s, I think he is making his most

significant interjections. He builds on the immediate postwar efforts that

Kim Phillips-Fein only hinted at in a chapter in her book, and he shows a

top-down story of corporate involvement that pairs nicely with the grassroots

efforts in crafting a Christian vision for government in southern California

that Dochuk detailed. For readers interested in the construction of

“religion,” Kruse has also provided a good example of, arguably, a composite,

politicized “religion” thought up in business-backed front groups and

proliferated by business-backed messengers, from upstart groups like James

Fifield’s Spiritual Mobilization and the Abraham Vereide’s Prayer Breakfast

movement to big-name players like Billy Graham, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Richard

Nixon, and others. To be sure, this was not the only vision of

“Christian America” and thus not the only form of this “new” (if we accept it

as new) “religion” advanced by business interests at mid-century. But as

Kruse writes, it was a “public religion” that cut across many denominational

lines and social groups and had millions of fervent disciples and

adherents. And it seemed, even more so than evangelicalism or

Catholicism, to provide clear-cut narrative regarding religion and the state

since, in large part, it was a religion that gave cosmic and ultimate meaning

to governmental activities.

|

| James Fifield |

Kruse sidesteps the

question of whether the fights over “One Nation Under God” actually won much

for corporate America. The era of deregulation and wealth redistribution

upwards since the 1960s is not discussed; hence, it is unclear exactly how “Christian

America” propaganda overlapped with the economic agenda that Phillips-Fein,

Moreton, and Dochuk detailed. But I get the sense that Kruse is not

interested in a redux of What’s the Matter With Kansas?, with

Americans hookwinked into supporting economic agendas that hurt them because

they so fervently believe in a religious vision of the nation that corporate

titans and their political shills spoon-fed them. Rather, it seems

to conclude closer to Moreton’s assertion that libertarianism—religious and

economic—are two sides of the same coin, with the former advancing the latter,

especially since both have become something of political gospel in national

debates over state, church, society, and enterprise. But again, that

argument is more implied in the first half of the book than explicated all the

way through.

More broadly, when

considering where Kruse’s book fits in the developing historiography on

business and religion in modern America, it definitely offers a challenge to

historians who consider the politics of consensus as a bottom-up or

corporate-less construction of the 1950s and 1960s, showing various debates

over the “Christian America” that corporate American invented. It also

downplays the Cold War as the cause of “Christian America” proclamations,

although Kruse does not dismiss fears of communism as important. He

simply argues that the New Deal was the primary cause of corporate pushes for a

new language of religious nationalism and citizenship.

That said, I found

it somewhat unfortunate that One Nation Under God also

re-affirms one of the reigning facets of the “new” business history, namely

that the “religious” and “political” turn in business history routinely

presents a kind of uncontested history of white America. Kruse’s

excellent first book, White Flight, was about white politics in an

age of civil rights. Similarly, One Nation Under God is

about white politics in an age of New Deal normalization and Cold War

anxiety—and an age of civil rights. The “public religion” that Kruse

describes, almost from beginning to end, is a religion made by whites,

ostensibly for affirmation by whites. But the politics of church and

state were not indistinct from conflicts over race, structural racism,

segregation, privacy rights and private spaces, from schools to

businesses. Here, however, they oddly are. Most of the critics of

the “Christian America” motif come from liberal white Protestants, certain Jews

and Catholics, or freer-thinking white Americans. But the foremost and

most strident critics of the “One Nation Under God” motif were the millions of

African-Americans, Japanese Americans, and Latinos who did not see a nation

under God, religious freedom, and equality. Their story, and how it fits

into the business history of American postwar religion, remains untold in this

book, as it does in the broader historiography on how corporate America shaped

the contours of American religion and vice-versa. (I could write

more about how a “Christian America” origins story is largely a patriarchal endeavor

as well, or primarily about state sanction for gendered orders, manly

militarism, breadwinner politics, and NIMBY forms of masculine defense,

especially when considering school prayers, public military rituals, and

pedagogy. But that might be best left to Seth Dowland’s forthcoming

book.)

Kruse’s book can

and should stand as both inspiration and a turning point, as an excellent place

to begin thinking about our historiographic pursuits, especially the strain of

historical writing that writes the output of business-religious interactions as

basically about white politics, and postwar religious history as about

explaining insurgent militarism, neoliberalism, and conservatism.

Kruse is correct to imply that big business helped to make the very categories

of “public religion” (or one category of “public religion”) in modern American

history. Our task as historians moving forward, I think, is to understand

how business might have helped to make the many counter-narratives to the one

that Kruse and other historians have aptly and skillfully uncovered so

far.

The first place to

start will be with a study that traces out the influence of corporate

executives and corporate power in the shaping of religious liberalism and the

religious meaning of, say, continuing postwar New Dealism. The “liberal”

turn in recent religious historiography has yet to make much room for business

power, and it will need to do so to avoid a rash characterization of

liberalism—religious and/or political—as somehow outside the corporate regime

and corporate negotiations and accommodations. Plenty of liberals appear

as corporate spokespersons or supporters of “Christian America” in Kruse’s

book. That story of liberal wrangling (negotiation? affirmation?

acculturation? resignation? resistance?) regarding corporate power and financial

support is as important as any stories of leftist, civil rights, or radical

activism inspired by religious aspirations or constructions. Race,

ethnicity, sexuality, and gender (save for in Moreton’s book) also remain

understudied in the new business histories of religion, as do others other than

Protestants. Local negotiations and conflicts between business and

religious individuals or groups also seem particularly sparse. We have a

good sense of how corporate Americans (often national figures or transnational)

make “Christian America” (a nationalist project). But if all politics is

local, then it is reasonable to assume that business is local as well, and the

production of religion at the local level via business, whether large or

small. Given that the federal state seems notably secularized,

despite all the rhetoric of “God Bless America” or “One Nation Under God,” it

would be instructive for scholars to consider how business and religious

interests formed mini-establishments or local havens or corporate-religious

dominance or division. “God Bless Mississippi” or “God Bless Utah,”

perhaps? “One Siler City Under God,” to cite Chad

Seales’s recent consideration of “public religion” and secular/business/liberal

modes and discourses in a southern town? Moving outward, it is

instructive to remember that Moreton argued for a global framework to

understand an activist, “religious” company like Wal-Mart. The

transnational endeavors of conservative evangelicals surely had business help

and should be investigated. A similar “global” framework might help to

elucidate other business-religious ventures in the modern era as well.

When drawn

together, business history and religious history should produce a kaleidoscope

of narratives that should push us to consider what it means to be “religious”

in a corporate age. “One Nation Under God” was one of many narratives

that business helped to construct or undercut, and hardly an uncomplicated

one. A better sense of the actual and uneven influence of business in

modern American religious constructions and narratives (in public and private

spaces, in national, transnational and local arenas) is the next step in writing

histories of a nation that, to revise Chesterton, strove to

believe it could fashion some sort of soul onto its institutions and

communities, arguably through a wide array of corporate means and private

sectors.

Comments