Conference Recap: National Museum of American History's Religion in Early America Symposium

Today's guest post comes from Charles Richter, a PhD candidate in American Religious History at George Washington University. He studies irreligion and its critics, apocalypticism, and their intersections with American culture. Charles attended the Religion in Early America symposium hosted by the National Museum of American History last week. Following Charles' lead, readers are welcome to submit guests posts from conferences or while visiting archives this spring and summer. Submissions should be emailed to Cara.

Charles Richter

Visitors to the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History could be forgiven for thinking that religion has not played a large role in the nation’s history. Most are more interested in seeing Dorothy’s ruby slippers anyway, but the stories told by the official repository of artifacts from United States history have largely steered clear of involving religion to any meaningful degree. This is about to change, thanks to the work of many prominent scholars of American religion. On March 20, NMAH hosted a symposium on Religion in Early America, organized by Stephen Prothero, to introduce the museum’s plans regarding religion and to discuss some major issues in its representation.

Introducing the symposium, NMAH director John Gray announced both an exhibit on religion in early America scheduled to open in 2017, on the second floor of the newly remodeled west wing, and the museum’s goal to hire a permanent curator of religion. The initial exhibit will be curated by David Allison, associate director of curatorial affairs, and guest curator Peter Manseau, whom many readers of this blog will know from his recent book One Nation Under Gods. The exhibit will include such artifacts as Lucretia Mott’s cloak, George Washington’s christening robe, and the Jefferson Bible, on which the museum recently performed significant conservation work.

In his opening and closing remarks, Prothero, who had initially been brought to NMAH on a fellowship following the God in America PBS series, described religion in America as “connected, contested, and complicated.” The challenge for the museum is to represent the interconnected nature of the stories of religion in America while also acknowledging the conflicts, not only between religious traditions, but also over the interpretations and definitions of religion itself. The exhibit and symposium both address three major themes: religious freedom, religious growth, and religious diversity.

The first panel of the day dealt with Religious freedom in early America, and featured David Sehat, Kathleen Flake, and Michelene Pesantubbee. On the question of what religious freedom meant to early Americans, Flake and Sehat agreed on the central idea that tensions between corporate and individual meanings of freedom dictated the groundwork for the legal framework we see today, but had differing opinions on how to interpret the shape of religious freedom generated by that tension. Sehat argued that the failure to disestablish the states following the ratification of the First Amendment makes religious history a “myth,” one that evangelicals could exploit by using the machinery of government to enforce their moralistic vision. Flake countered that the same forces that produced the First Amendment were still at play in the states at a socio-cultural level, eventually producing law. Pesantubbee reminded the panel that the federal government’s punt to the states caused problems for the religious freedom of native peoples; they had hoped that the federal government would step in on their behalf, but it had protected the states’ position instead. Prothero threw the panel a softball: “Was America founded as a Christian nation?” The “United States of America” was founded as a de facto Christian nation, said Pesantubbee, although that entity excluded vast numbers of people. Sehat suggested that it already was a Christian nation, and the godless Constitution did not change that situation very much. Flake added that “We the People” implies a reflection of the nature of the people in the nature of the nation, leading to a constantly shifting answer to that question.

Next up was a panel on Religious Growth in the Second Great Awakening, with Amanda Porterfield, David Holland, and John Wigger. The primary message from this panel was the complexity of religious growth: the growth of new denominations, the genesis of explosive new religious movements, and the rise of the Black church as the institution of slavery expanded. All three panelists focused on the importance of the interaction between new denominations and slavery; Holland argued that the tone of Second Great Awakening theology was more appealing to enslaved people, with its message of otherworldly liberation and the individual’s agency with regard to salvation. Porterfield added that me must recognize the Faustian bargain that America made by using that theology to police the borders of enslavement. The fact that a single denomination could produce radically different views of abolition in different regions of the country, said Wigger, speaks to the power of the separation of church and state: with no ties to state sponsorship, culture could shape doctrine at a more granular level. Porterfield identified the combination of democratization and authoritarianism that characterized the new denominations and movements of this era as a prime attraction for the many Americans who had previously held no formal church affiliation. The Mormons, for example, fused these two contradictory drives especially well, providing in Utah both an egalitarian refuge and a strict moral framework.

The final panel of the day, on Religious Diversity, featured Nancy Schultz, Michael Gomez, and Kathryn Gin Lum, with moderator Peter Manseau, who began by asking whether the metaphor of “weaving” used recently by President Obama to describe the integration of Islam into American culture is a myth. To Gomez, the metaphor works in that Muslims have been part of the Americas from the beginning of colonization, but it breaks down because their experience has tended to be very concentrated and marginalized. For Catholics, according to Schultz, the metaphor of weaving is particularly apt, especially in a place like Boston that retains so many of the original threads of both the Catholic and Protestant cultures that shaped it. Gin Lum complicated the question, saying that as the nation was “founded” at several points in history, the American cloth is woven from several existing pieces of fabric, often violently cut and stitches together. The divisions in this cloth have helped define both the nation and the various religious traditions: Catholics and Protestants each needed the other as a hellbound opposite to define themselves and attract converts, especially among Native Americans and enslaved people. But religions themselves were also converted, said Gomez. Both Islamic and non-Islamic African religious traditions are embedded in the theology and liturgical style of African-American churches. Especially in a museum setting, said Gin Lum, sources other than texts are necessary to represent religious history more comprehensively. Historians’ privileging of texts has led to a Protestant-tinted interpretation that fails traditions that do not rely on texts so heavily. Supporting slavery was sometimes a way for minority religions to assert their American credentials or find their place in the existing power structures. Catholic immigrants, although accused by Protestants of being enslaved to their own church, often supported slavery because it seemed like the more American, less radical, position to take. Until the 1830s, free Muslims in the Americas tended toward conservatism, often holding slaves and even putting down slave revolts, thus asserting their status in a highly stratified society.

The three panels covered much more ground than can be related here. Although the conversation seldom turned to the challenges inherent in representing religion at NMAH, the complications that arose should help inform how the museum handles the task. The main challenge NMAH faces is to use objects from the collections as evidence for the complex and interconnected stories of religions in America, not as simple curiosity pieces. This is difficult for at least two reasons: first, the NMAH audience is typically fast-paced and not especially receptive to nuanced stories; and second, the Smithsonian is a quasi-federal agency that is in part dependent on congressional funding. The museum must has to worry about a congress willing to interfere with exhibits its constituents might find offensive. With the uproar over the insufficiently American-exceptionalist AP U.S. History exam, NMAH may well see a complicating exhibit on religion met with the same backlash that faced the Hide/Seek exhibit at the National Portrait Gallery. Many Americans will demand that a curator of religion at the National Museum of American History be committed to a self-congratulatory view of the subject.

The fact that John Gray has sought out a wide range of scholars of American religion gives me hope that the museum will be able to sustain this initiate, however. Peter Manseau is no stranger to pushback from people who do not want their view of American religious history complicated. He has an enormous undertaking ahead of him. Stephen Prothero should be congratulated on assembling this group of scholars, not only for this symposium, but also for a two-day symposium held in December of 2013, where scholars presented the NMAH community with overviews of various religious traditions in America, including Islam, Catholicism, Protestantism, Hinduism, Yoruba, Secularism, Native American Religion, Judaism, and Buddhism.*

The challenge of representing American religion is difficult enough when writing for an academic audience or popular press; when one attempts to do so under the aegis of the National Museum of American History, a whole new suite of troubles is possible. As Prothero said, the study of religion is indeed rocket science, although at least the math is easier.

*The lineup for the first symposium included:

Omid Safi on Islam

Julie Bryne on Catholicism

David Morgan on Protestantism

Vasudha Narayanan on

Tracey Hucks on Yoruba

Leigh Schmidt on Secularism

Gabrielle Tayac on Native American Religion

Hasia Diner on Judaism

Tom Tweed on Buddhism in America

Charles Richter

Visitors to the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History could be forgiven for thinking that religion has not played a large role in the nation’s history. Most are more interested in seeing Dorothy’s ruby slippers anyway, but the stories told by the official repository of artifacts from United States history have largely steered clear of involving religion to any meaningful degree. This is about to change, thanks to the work of many prominent scholars of American religion. On March 20, NMAH hosted a symposium on Religion in Early America, organized by Stephen Prothero, to introduce the museum’s plans regarding religion and to discuss some major issues in its representation.

|

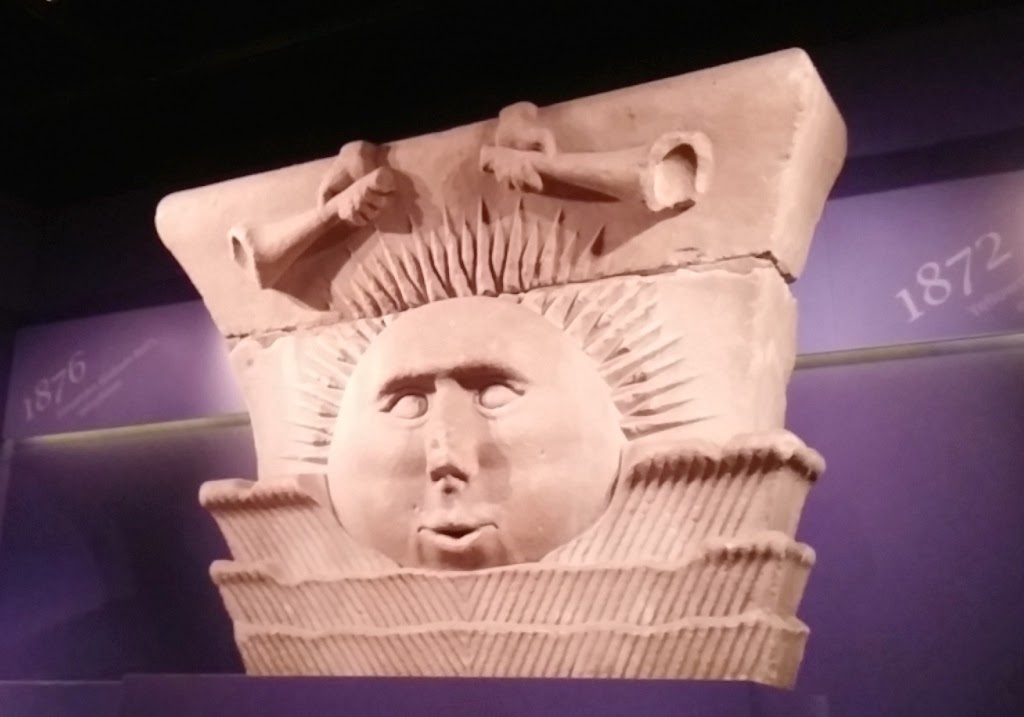

| Mormon sunstone capital from the original Nauvoo temple (currently on display at the National Museum of American History) Photo by Charles Richter, 2015 |

In his opening and closing remarks, Prothero, who had initially been brought to NMAH on a fellowship following the God in America PBS series, described religion in America as “connected, contested, and complicated.” The challenge for the museum is to represent the interconnected nature of the stories of religion in America while also acknowledging the conflicts, not only between religious traditions, but also over the interpretations and definitions of religion itself. The exhibit and symposium both address three major themes: religious freedom, religious growth, and religious diversity.

The first panel of the day dealt with Religious freedom in early America, and featured David Sehat, Kathleen Flake, and Michelene Pesantubbee. On the question of what religious freedom meant to early Americans, Flake and Sehat agreed on the central idea that tensions between corporate and individual meanings of freedom dictated the groundwork for the legal framework we see today, but had differing opinions on how to interpret the shape of religious freedom generated by that tension. Sehat argued that the failure to disestablish the states following the ratification of the First Amendment makes religious history a “myth,” one that evangelicals could exploit by using the machinery of government to enforce their moralistic vision. Flake countered that the same forces that produced the First Amendment were still at play in the states at a socio-cultural level, eventually producing law. Pesantubbee reminded the panel that the federal government’s punt to the states caused problems for the religious freedom of native peoples; they had hoped that the federal government would step in on their behalf, but it had protected the states’ position instead. Prothero threw the panel a softball: “Was America founded as a Christian nation?” The “United States of America” was founded as a de facto Christian nation, said Pesantubbee, although that entity excluded vast numbers of people. Sehat suggested that it already was a Christian nation, and the godless Constitution did not change that situation very much. Flake added that “We the People” implies a reflection of the nature of the people in the nature of the nation, leading to a constantly shifting answer to that question.

Next up was a panel on Religious Growth in the Second Great Awakening, with Amanda Porterfield, David Holland, and John Wigger. The primary message from this panel was the complexity of religious growth: the growth of new denominations, the genesis of explosive new religious movements, and the rise of the Black church as the institution of slavery expanded. All three panelists focused on the importance of the interaction between new denominations and slavery; Holland argued that the tone of Second Great Awakening theology was more appealing to enslaved people, with its message of otherworldly liberation and the individual’s agency with regard to salvation. Porterfield added that me must recognize the Faustian bargain that America made by using that theology to police the borders of enslavement. The fact that a single denomination could produce radically different views of abolition in different regions of the country, said Wigger, speaks to the power of the separation of church and state: with no ties to state sponsorship, culture could shape doctrine at a more granular level. Porterfield identified the combination of democratization and authoritarianism that characterized the new denominations and movements of this era as a prime attraction for the many Americans who had previously held no formal church affiliation. The Mormons, for example, fused these two contradictory drives especially well, providing in Utah both an egalitarian refuge and a strict moral framework.

The final panel of the day, on Religious Diversity, featured Nancy Schultz, Michael Gomez, and Kathryn Gin Lum, with moderator Peter Manseau, who began by asking whether the metaphor of “weaving” used recently by President Obama to describe the integration of Islam into American culture is a myth. To Gomez, the metaphor works in that Muslims have been part of the Americas from the beginning of colonization, but it breaks down because their experience has tended to be very concentrated and marginalized. For Catholics, according to Schultz, the metaphor of weaving is particularly apt, especially in a place like Boston that retains so many of the original threads of both the Catholic and Protestant cultures that shaped it. Gin Lum complicated the question, saying that as the nation was “founded” at several points in history, the American cloth is woven from several existing pieces of fabric, often violently cut and stitches together. The divisions in this cloth have helped define both the nation and the various religious traditions: Catholics and Protestants each needed the other as a hellbound opposite to define themselves and attract converts, especially among Native Americans and enslaved people. But religions themselves were also converted, said Gomez. Both Islamic and non-Islamic African religious traditions are embedded in the theology and liturgical style of African-American churches. Especially in a museum setting, said Gin Lum, sources other than texts are necessary to represent religious history more comprehensively. Historians’ privileging of texts has led to a Protestant-tinted interpretation that fails traditions that do not rely on texts so heavily. Supporting slavery was sometimes a way for minority religions to assert their American credentials or find their place in the existing power structures. Catholic immigrants, although accused by Protestants of being enslaved to their own church, often supported slavery because it seemed like the more American, less radical, position to take. Until the 1830s, free Muslims in the Americas tended toward conservatism, often holding slaves and even putting down slave revolts, thus asserting their status in a highly stratified society.

The three panels covered much more ground than can be related here. Although the conversation seldom turned to the challenges inherent in representing religion at NMAH, the complications that arose should help inform how the museum handles the task. The main challenge NMAH faces is to use objects from the collections as evidence for the complex and interconnected stories of religions in America, not as simple curiosity pieces. This is difficult for at least two reasons: first, the NMAH audience is typically fast-paced and not especially receptive to nuanced stories; and second, the Smithsonian is a quasi-federal agency that is in part dependent on congressional funding. The museum must has to worry about a congress willing to interfere with exhibits its constituents might find offensive. With the uproar over the insufficiently American-exceptionalist AP U.S. History exam, NMAH may well see a complicating exhibit on religion met with the same backlash that faced the Hide/Seek exhibit at the National Portrait Gallery. Many Americans will demand that a curator of religion at the National Museum of American History be committed to a self-congratulatory view of the subject.

The fact that John Gray has sought out a wide range of scholars of American religion gives me hope that the museum will be able to sustain this initiate, however. Peter Manseau is no stranger to pushback from people who do not want their view of American religious history complicated. He has an enormous undertaking ahead of him. Stephen Prothero should be congratulated on assembling this group of scholars, not only for this symposium, but also for a two-day symposium held in December of 2013, where scholars presented the NMAH community with overviews of various religious traditions in America, including Islam, Catholicism, Protestantism, Hinduism, Yoruba, Secularism, Native American Religion, Judaism, and Buddhism.*

The challenge of representing American religion is difficult enough when writing for an academic audience or popular press; when one attempts to do so under the aegis of the National Museum of American History, a whole new suite of troubles is possible. As Prothero said, the study of religion is indeed rocket science, although at least the math is easier.

*The lineup for the first symposium included:

Omid Safi on Islam

Julie Bryne on Catholicism

David Morgan on Protestantism

Vasudha Narayanan on

Tracey Hucks on Yoruba

Leigh Schmidt on Secularism

Gabrielle Tayac on Native American Religion

Hasia Diner on Judaism

Tom Tweed on Buddhism in America

Comments

Of questionable accuracy:Pretty much it was just the one. Mr. Manseau is entitled to a contrary opinion of course, but "under Gods" is more a term of art than museum-quality fact.