"The Heavenly Vision" of Suffrage, or, Happy Belated Anna Howard Shaw Day!

Carol Faulkner

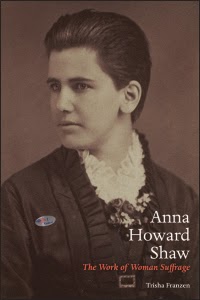

In 1888, the Rev. Anna Howard Shaw preached the opening sermon at the first meeting of the International Council of Women. Based on Acts 26:19, "Whereupon, O, King Agrippa, I was not disobedient unto the heavenly vision," she argued that all reformers experienced a call from God: "Every reformer the world has ever seen has had a similar experience.... No one of God's children has ever gone forth to the world who has not first had revealed to him his mission, in a vision."* Shaw reviewed the diverse visions of the women gathered in Washington, D.C., representing multiple organizations and nations. The suffragist had a "vision of political freedom," "that humanity everywhere must be lifted out of subjection into the free and full air of divine liberty." The moral reformer, or social purist, had a vision of "social freedom," in which they defeated prostitution by holding men as well as women accountable for sexual sins (her definition of "social freedom" is somewhat jarring to modern readers). The temperance reformer had seen the "rum fiend" guiding the "ship of State" to the "rocks of destruction." The educator envisioned "the great field of knowledge which the Infinite has spread before the world." Anna Howard Shaw had experienced such a vision herself. As a teenager, living in poverty in rural Michigan, she had experienced a call to preach, though it would be years before she was able to implement it. By the 1890s, according to biographer Trisha Franzen, suffrage was a religion to Shaw, who became the longest serving president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). How did this transformation occur?

Born on Feb. 14, 1847 in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, England, Shaw immigrated to the U.S. with her family when she was four years old. Even as a child, Shaw's labor was essential to her family's survival, and Franzen views Shaw's status as an immigrant, and then a working woman, as central to her perspective on women's rights. In 1857, still searching for a better life, the family moved again

from Lawrence, Massachusetts, to Mecosta County, Michigan. Her religious vision came shortly after the move to western Michigan, when her father's poor choices had compounded the family's struggles. According to Franzen, "Anna had spent the day in the woods with her books and her dreams. This day, alone with the trees and her thoughts, she felt the call of vocation. She was awed by the experience of feeling God's will, telling her to preach and lead people to salvation." Her Unitarian family was unsupportive. When she was twenty-three, Shaw finally left their farm to move to Big Rapids. She attended high school, converted to the Methodism, preached her first sermons, and enrolled at Albion College.

Shaw's experiences in the Methodist Church pushed her toward suffrage. Franzen opens with a wonderful story about Shaw carrying a gun with her on missions in the Michigan frontier, an example of her willingness to defy gender norms. Her preaching subsidized her education, and she left Albion to attend Boston University School of Theology. A co-educational institution, the school nevertheless refused to ordain her. Instead, Shaw became the pastor of a Free Methodist Church in Dennis, Massachusetts. Preaching was one thing apparently, and ordination quite another. With a colleague named Anna Oliver, she pressured the Methodist Episcopal Church to accept female ordination, only to have her license to preach withdrawn. Instead, in 1880, Shaw found brief acceptance in another church, the Methodist Protestant Church. As Franzen writes, however, "even after she was ordained, the young men in the Methodist Protestant Conference went out of their way to make her week there miserable. While Shaw maintained her ministerial credentials for most of the rest of her life, she never returned to a single Conference gathering." By 1885, she left her parish in Dennis to devote herself to women's rights, at first affiliating with Lucy Stone in the still divided movement. Converted anew after she met Susan B. Anthony, Shaw devoted her considerable speaking skills, developed as a Methodist preacher, to the cause of suffrage.

As her sermon to the International Council of Women makes clear, Shaw's religious calling, now independent of any institution, continued to be an important part of her suffrage work. Franzen notes one of her frequent suffrage speeches was a Biblical analysis titled "God's Women." As President of NAWSA, she preached in a church in Stockholm, Sweden, apparently the first woman to do so. Shaw remembered the sermon as "an otherworldly experience in which her spiritual self fully directed her physical being." During this time, Shaw dropped the "Reverend" in favor of "Doctor." Though the title could have indicated her medical degree, which she never used, it is more likely to refer to her theological credentials. Unlike many of her fellow suffragists, Shaw needed to earn her living, and her degree had given her an authority that her class background had not.

Now misunderstood, and even forgotten, Franzen recovers Shaw as the greatest feminist orator of her time. As she shows, Shaw was also a complicated, and sometimes difficult, person. Franzen believes that Shaw's background as a preacher, immigrant, and working-class woman caused her to clash with fellow suffragists even as she connected with diverse audiences. Franzen rightly urges more analysis of Shaw's place in suffrage history, including her thousands of speeches. Religion is one aspect of Shaw's life that deserves more attention. For Franzen's purpose, Shaw's religion is utilitarian, something that propelled her from rural poverty and isolation onto a national stage. I think Shaw's religious faith might tell us even more about the uneasy relationship between organized religion and the women's rights movement. For example, with other members of NAWSA, Shaw voted to disassociate the organization from Elizabeth Cady Stanton's Woman's Bible. How much of her conflict with other feminists involved religion?

In 1888, Shaw's conflicts with other suffragists were in the future. She concluded her "Heavenly Vision" sermon with a brief lesson in women's history. "Some years ago," in 1840, before Shaw was born, the "arrogance and pride" of men at the World's Anti-Slavery Convention in London had excluded women from participation. But in that "prejudice," God gave women a "grand vision" "manifested here" in the International Council of Women. Shaw concluded, "it is but the dawning of a new day...when the vision which we are now beholding, which is beaming in the soul of one, shall enter the hearts and transfigure the lives of all."** Shaw, who died in 1919, did not live to see her vision fulfilled, but her contributions to the cause deserve to be part of this history. Franzen's biography is an excellent start.

* Shaw's sermon can be found in History of Woman Suffrage, Vol. 4, available on the Woman and Social Movements database.

** For the way this inaugural meeting of the International Council of Women shaped the history of the women's rights movement, see Lisa Tetrault, The Myth of Seneca Falls.

In 1888, the Rev. Anna Howard Shaw preached the opening sermon at the first meeting of the International Council of Women. Based on Acts 26:19, "Whereupon, O, King Agrippa, I was not disobedient unto the heavenly vision," she argued that all reformers experienced a call from God: "Every reformer the world has ever seen has had a similar experience.... No one of God's children has ever gone forth to the world who has not first had revealed to him his mission, in a vision."* Shaw reviewed the diverse visions of the women gathered in Washington, D.C., representing multiple organizations and nations. The suffragist had a "vision of political freedom," "that humanity everywhere must be lifted out of subjection into the free and full air of divine liberty." The moral reformer, or social purist, had a vision of "social freedom," in which they defeated prostitution by holding men as well as women accountable for sexual sins (her definition of "social freedom" is somewhat jarring to modern readers). The temperance reformer had seen the "rum fiend" guiding the "ship of State" to the "rocks of destruction." The educator envisioned "the great field of knowledge which the Infinite has spread before the world." Anna Howard Shaw had experienced such a vision herself. As a teenager, living in poverty in rural Michigan, she had experienced a call to preach, though it would be years before she was able to implement it. By the 1890s, according to biographer Trisha Franzen, suffrage was a religion to Shaw, who became the longest serving president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). How did this transformation occur?

Shaw's experiences in the Methodist Church pushed her toward suffrage. Franzen opens with a wonderful story about Shaw carrying a gun with her on missions in the Michigan frontier, an example of her willingness to defy gender norms. Her preaching subsidized her education, and she left Albion to attend Boston University School of Theology. A co-educational institution, the school nevertheless refused to ordain her. Instead, Shaw became the pastor of a Free Methodist Church in Dennis, Massachusetts. Preaching was one thing apparently, and ordination quite another. With a colleague named Anna Oliver, she pressured the Methodist Episcopal Church to accept female ordination, only to have her license to preach withdrawn. Instead, in 1880, Shaw found brief acceptance in another church, the Methodist Protestant Church. As Franzen writes, however, "even after she was ordained, the young men in the Methodist Protestant Conference went out of their way to make her week there miserable. While Shaw maintained her ministerial credentials for most of the rest of her life, she never returned to a single Conference gathering." By 1885, she left her parish in Dennis to devote herself to women's rights, at first affiliating with Lucy Stone in the still divided movement. Converted anew after she met Susan B. Anthony, Shaw devoted her considerable speaking skills, developed as a Methodist preacher, to the cause of suffrage.

As her sermon to the International Council of Women makes clear, Shaw's religious calling, now independent of any institution, continued to be an important part of her suffrage work. Franzen notes one of her frequent suffrage speeches was a Biblical analysis titled "God's Women." As President of NAWSA, she preached in a church in Stockholm, Sweden, apparently the first woman to do so. Shaw remembered the sermon as "an otherworldly experience in which her spiritual self fully directed her physical being." During this time, Shaw dropped the "Reverend" in favor of "Doctor." Though the title could have indicated her medical degree, which she never used, it is more likely to refer to her theological credentials. Unlike many of her fellow suffragists, Shaw needed to earn her living, and her degree had given her an authority that her class background had not.

Now misunderstood, and even forgotten, Franzen recovers Shaw as the greatest feminist orator of her time. As she shows, Shaw was also a complicated, and sometimes difficult, person. Franzen believes that Shaw's background as a preacher, immigrant, and working-class woman caused her to clash with fellow suffragists even as she connected with diverse audiences. Franzen rightly urges more analysis of Shaw's place in suffrage history, including her thousands of speeches. Religion is one aspect of Shaw's life that deserves more attention. For Franzen's purpose, Shaw's religion is utilitarian, something that propelled her from rural poverty and isolation onto a national stage. I think Shaw's religious faith might tell us even more about the uneasy relationship between organized religion and the women's rights movement. For example, with other members of NAWSA, Shaw voted to disassociate the organization from Elizabeth Cady Stanton's Woman's Bible. How much of her conflict with other feminists involved religion?

In 1888, Shaw's conflicts with other suffragists were in the future. She concluded her "Heavenly Vision" sermon with a brief lesson in women's history. "Some years ago," in 1840, before Shaw was born, the "arrogance and pride" of men at the World's Anti-Slavery Convention in London had excluded women from participation. But in that "prejudice," God gave women a "grand vision" "manifested here" in the International Council of Women. Shaw concluded, "it is but the dawning of a new day...when the vision which we are now beholding, which is beaming in the soul of one, shall enter the hearts and transfigure the lives of all."** Shaw, who died in 1919, did not live to see her vision fulfilled, but her contributions to the cause deserve to be part of this history. Franzen's biography is an excellent start.

* Shaw's sermon can be found in History of Woman Suffrage, Vol. 4, available on the Woman and Social Movements database.

** For the way this inaugural meeting of the International Council of Women shaped the history of the women's rights movement, see Lisa Tetrault, The Myth of Seneca Falls.

Comments