(Today's post is by Cassandra L. Yacovazzi, who just this month defended her dissertation and received a Ph.D. in History from the University of Missouri -- our congratulations to her! Cassandra joined 23 scholars (graduate students, professors, and archivists) in Rome from June 6-19, 2014, for the 2014 Rome Seminar, sponsored by the Cushwa Center as well as several other entities at the University of Notre Dame: Italian Studies, the Nanovic Institute for European Studies, the College of Arts and Letters, and the Office of Research. The Cushwa Center, which already offers the Peter R. D'Agostino Research Travel Grant for research in Italian archives, plans to offer a Rome Seminar on a regular basis, and is currently developing a guide to Roman archives for scholars interested in American Catholicism.)

|

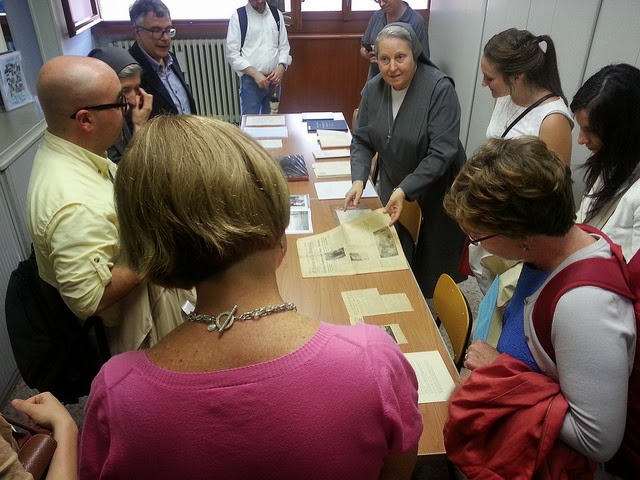

| Participants in the 2014 Rome Seminar at the Salesian Archives |

Cassandra L. Yacovazzi

I consider myself a historian of U.S. Catholicism (my research focuses on anti-Catholicism and anti-convent/nun sentiment in the U.S. in the first half of the nineteenth century). I’ve never thought of myself as a transatlantic historian, let alone a global historian. But my experience participating in the 2014 Rome Seminar impressed upon me the global reach of my subject. The seminar, entitled “American Catholicism in a World Made Small: Transnational Approaches to US Catholic History,” featured presentations by a series of prominent historians and visits to key archives in Rome.

|

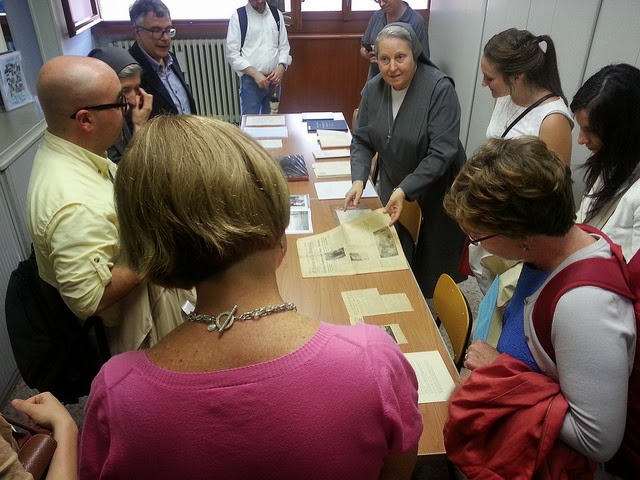

| The 2014 Rome Seminar Hard at Work |

In the seminar's opening talk, Simon Ditchfield from the University of York encouraged seminar participants to think of Rome not only as a place, but also a malleable concept, setting the tone for talks to follow. True to Ditchfield's concept, I found that simply being in the “eternal city” overwhelmed me with a sense of the connectedness of Catholic history in time and place. For anti-Catholics in nineteenth century America, “Romanism” stood for decadence and decay; the city’s grandeur itself symbolized all that they feared and found fascinating about Catholicism. For Catholics, Rome symbolized institutional authority and Catholic triumph, offering a storehouse of relics of the most revered saints and a well-spring of missionary efforts, funding, and doctrine. Either way, Rome was in America. Walking through the Piazza San Pietro toward the Vatican, I thought about how decisions made there have shaped Europe, the U.S. and the rest of the world for centuries. Participating in the Corpus Christi Mass at the Basilica of San Giovanni led by Pope Francis impressed upon me not only the historical importance of the moment but also of the past. Emperor Constantine erected the basilica as the first Christian church in Rome. Being there seemed to make real for me the concept of “a world made small.”

While

all of the presentations offered a rich breadth of information, a snapshot of a few displays some of the innovative approaches to American Catholicism being undertaken by historians. Timothy Matovina’s presentation challenged a history of U.S. exceptionalism by assuming a hemispheric (rather than just U.S.) approach to American religion. John T. McGreevy provided an illuminating example of how global Catholic history can be done in a presentation on his current project on nineteenth century Jesuits in the U.S. Daniele Fiorentino, of the Università di Roma Tre, discussed the peculiar diplomatic relationship between the U.S., Italy, and the Vatican since 1870 -- a political background which shaped interactions between Catholics and non-Catholics in America. And finally, Kathleen Cummings discussed her upcoming book Citizen Saints, describing how a transnational approach had informed her research on the process of canonizing "American saints."

|

| Transnational Material Culture! |

Visiting seven Catholic archives throughout Rome, including the Vatican Secret Archives, provided overwhelming evidence of Catholicism’s global reach. Historians of American Catholicism, who have worked largely in American archives, might find the necessity of dealing with foreign archives inhibiting; demystifying Roman archives is a necessity for a transnational approach to Catholic history, however. We enjoyed going over useful vocabulary for navigating the Roman archives, such as “la fonte” (the source), “la cartella” (the folder), and “vorrei visitare l’archivo” (I would like to visit the archive). But while knowing these and other terms and phrases certainly is helpful, all the archivists that we met spoke English and were very approachable. Since I study the history of American women religious, of all our visits the one we made to the General Archives of the Society of the Sacred Heart and the Archive of the Daughters of Mary Help of Christians interested me the most and helped me to consider the importance of the transnational and often global character of religious orders. The General Archives of the Society of the Sacred Heart houses biographies, letters, Constitutions, and Approbations for the order from the early nineteenth century to the present, from the motherhouse to provinces in the U.S. and all over the world; the Daughters of Mary have had a missionary presence in 94 countries, and their archives, too, testify to the global nature of Catholicism.

|

| The 2014 Rome Seminar Hard at Work |

Going back to my current home in Columbia, Missouri to work on my dissertation, made my Rome experience seem like a dream. Yet I haven't been able to look at my work in quite the same way since. I’ve become more aware of depictions of the “Old World” in the anti-convent literature I examine. I’ve also become more sensitive to the relationship different women’s religious orders in America had with their motherhouses, which were often in Europe. I still need to explore these questions to give them justice in my project, which does of course, mean more work. But I’m intrigued by the new angles and intricate connections across cultural, national, and religious boundaries. And I hope that the exploration takes me back to Rome.

Comments