The Century Old Rhetoric of Bill Maher, Reza Aslan, and Cornel West

John L. Crow

Recently the social media sites have been abuzz with the debate about Islam, especially focusing on Bill Maher’s interlocutors taking center stage. It would be excessively repetitive to point out how both sides of the debate are simplistic and prone to generalizations. Instead, I would refer you to Steven Ramey’s post on the Culture on the Edge blog. For this blog post, I want to focus on a speech that took place over a century ago, one presented at the World Parliament of Religions in 1893. I want to focus on this speech because, by looking it, we can see how the conversation about the nature of Islam took place over a century ago mirrors the conversation about Islam today.

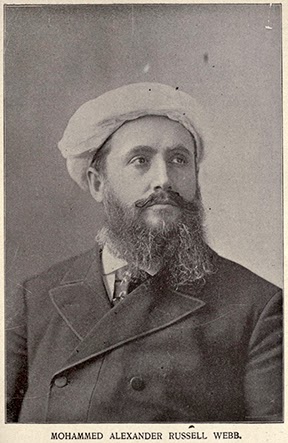

Mohammed Alexander Russell Webb was the only representative for Islam who spoke at the World Parliament of Religions in 1893. Though Webb was raised a Christian, he lived his life as a seeker as pointed out in the biography A Muslim in Victorian America: The Life of Alexander Russell Webb by Umar F. Abd-Allah (Oxford 2006). One significant influence on Webb was Theosophy, and it was through this influence he went searching for a new religion. He was appointed Consular Representative to the Philippines at the U.S. office at Manila and while in the Philippines in 1888 converted to Sunni Islam. From that time forward, he became an outspoken proponent for the tradition, establishing the American Muslim Propagation Movement in New York and an English based newspaper called Moslem World. It was in this context that he spoke at the World Parliament in Chicago.

Webb opens his speech pointing out the bias against Islam present in the West, especially America. He states, “There are several reasons why Islam and the character of its followers are so little understood in Europe and America, and one of these is that when a man adopts, or says he adopts, Islam, he becomes known as a Mussulman [i.e. Muslim] and his nationality becomes merged in his religion.” Webb continues, “If a Mohammedan, Turk, Egyptian, Syrian or African commits a crime the newspaper reports do not tell us that it was committed by a Turk, an Egyptian, a Syrian or an African, but by a Mohammedan. If an Irishman, an Italian, a Spaniard or a German commits a crime in the United States, we do not say that it was committed by a Catholic, a Methodist or a Baptist, nor even a Christian; we designate the man by his nationality. … But, just as soon as a membership of the East is arrested for a crime or misdemeanor, he is registered as a representative of the religion his parents followed or he adopted.”

In a recent debate between Reza Aslan and CNN reporters, referring back to what Aslan said to Bill Maher, Aslan argued that the monolithic representation of Islam loses its national and regional character. When Maher and reporters characterized Islam in different ways, Aslan responded “which Islam?” For instance, when asked about the treatment of women in Muslim countries, one reporter asked, “[in Muslim countries] for the most part, it is not a free and open society for women in those states.” Aslan replied, “It certainly is in Indonesia and Malaysia. It certainly is in Bangladesh. It certainly is in Turkey. I mean, again, this is the problem is that you're talking about a religion of 1.5 billion people and certainly it becomes very easy to just simply paint them all with a single brush by saying, well, in Saudi Arabia, they can't drive and so therefore that is somehow representative of Islam.”

Specifically about violence Webb asks, “If one or a dozen of these [Muslims] should commit an act of brutal intolerance or fanaticism, would it be just to say that it was due to the meritable tendencies of their religion?” His answer is very similar to Aslan’s reply when asked “if Islam promote[s] violence?” Aslan replies, “Islam is just a religion, and like every religion in the world, it depends on what you bring to it. If you're a violent person, your Islam, your Judaism, your Christianity, your Hinduism is going to be violent.”

For his part, Webb gives an early version of the repeated claim that the majority of Muslims are peaceful. Denying the statement that a Muslim goes “directly to Paradise” if he dies killing a Christian, he says, instead, this is a lie to “injure as peaceful and non-aggressive a class of people as the world has ever seen.”

This same rhetoric is not just reiterated by Aslan. The recent conversation between Bill Maher, Cornel West, and John Avalon, author of the book, Wingnuts, maintain the same tropes. After Maher continues the same wide sweeping generalizations about Islam, both his own and quoting those of others, West continues the rhetoric of internal difference, giving it his own spin. “The claim that quotes makes, the juxtaposition between liberals versus Islam, as if Islam is homogenous, there are prophetic Islamic figures who argue for liberties, for tolerance, for equality, beginning with Malcom X. Beginning with Mahmoud Mohammed Taha. There is a whole tradition within Islam that argues for rights, tolerance, and all this.”

John Avalon agrees and adds the rhetoric about peaceful Muslims, “You got to be able to confront the very real obvious threat we have been confronting as western liberal democracies for a long time while making the assumption, the clear separation between the vast majority of Muslims who are peaceful, I would argue, and a virulent strain of radical Islamism and Islamists who have been hell-bent on murdering as many people as possible for the past decade and a half.”

West rejoins, “But based on Brother Bill’s argument, the history of Christianity killing Jews, or the history of American Christians lynching black people would be the only statement for Christianity. That’s simply not true.” West’s rejoinder repeats the point that Islam being tread differently than other religions.

Recurrently we have the same rhetoric in this debate: Muslims are painted with a broad brush, the sweeping generalizations applied to Islam are not applied to other religions, we need to see that there are significant differences between different Muslims, Muslim communities, and Muslim nations, and that the majority of Muslims in the world are peaceful. This was the rhetoric for Webb at the 1893 World Parliament of Religion, and it stays the same today.

There are differences of course. The issues of polygamy in Islam, how Mohammed and his successors spread the religion by the sword, or that slavery is part of Islam, are less of an issue, but they still are discussed. Webb addressed these representations. Yet there are new ones that have emerged since Webb, often dealing with female oppression, such as female genital mutilation, to which Aslan replies, “It's a Central African problem” and not a Muslim one. Or the lack of rights women have, to which Aslan claims is only some Muslim countries, but not all. Sometimes the old issues reemerge in the new discourses about women, such as this recent essay about polygamy and women's rights in Pakistan.

While the differences are important, I find the similarities both significant and troubling. It means there really is little changing in the public debates, and the same tired points are rehashed time and again. As scholars of religion, who try to have nuance, in historical and critical conversations about these subjects, the lack of advancement regarding the public discourse about Islam is signals a larger problem. There is plenty of scholarship addressing all the points well, and push back against the generalizations on both sides. But what effect has this scholarship had on the overall discourse? Unfortunately, it seems little. This is even true for scholars like Aslan and West. Both these scholars deploy the same century-old rhetoric.

After converting to Islam, Webb addressed his fellow Theosophists, telling them of the greatness of Islam and how it had much in common with the Eastern religions they valorized. Webb went so far as to claim, “If I could take the reader by the hand and lead him along the path I have traveled … I feel assured that I could convince him that, to be a Theosophist, one must be a follower of Islam.” Theosophists rejected his claim. One replied, “But it is natural that the religion of Mohammed has not received from Western people a very great consideration. They judge it in the mass, and not from some of its teachings. The West developed its social system and its religious belief on its own lines, and having seen that many followers of the Prophet are polygamists, which is contrary to Western notions, the entire Islamic system has been condemned on that ground, both in a social and religious sense.” Today Islam is still judged as “contrary to Western notions” and “condemned on that ground, both in a social and religious sense” regardless of what scholars say. As a result, the rhetoric about Islam, over a century after Webb’s speech, is still the same.

Recently the social media sites have been abuzz with the debate about Islam, especially focusing on Bill Maher’s interlocutors taking center stage. It would be excessively repetitive to point out how both sides of the debate are simplistic and prone to generalizations. Instead, I would refer you to Steven Ramey’s post on the Culture on the Edge blog. For this blog post, I want to focus on a speech that took place over a century ago, one presented at the World Parliament of Religions in 1893. I want to focus on this speech because, by looking it, we can see how the conversation about the nature of Islam took place over a century ago mirrors the conversation about Islam today.

Mohammed Alexander Russell Webb was the only representative for Islam who spoke at the World Parliament of Religions in 1893. Though Webb was raised a Christian, he lived his life as a seeker as pointed out in the biography A Muslim in Victorian America: The Life of Alexander Russell Webb by Umar F. Abd-Allah (Oxford 2006). One significant influence on Webb was Theosophy, and it was through this influence he went searching for a new religion. He was appointed Consular Representative to the Philippines at the U.S. office at Manila and while in the Philippines in 1888 converted to Sunni Islam. From that time forward, he became an outspoken proponent for the tradition, establishing the American Muslim Propagation Movement in New York and an English based newspaper called Moslem World. It was in this context that he spoke at the World Parliament in Chicago.

Webb opens his speech pointing out the bias against Islam present in the West, especially America. He states, “There are several reasons why Islam and the character of its followers are so little understood in Europe and America, and one of these is that when a man adopts, or says he adopts, Islam, he becomes known as a Mussulman [i.e. Muslim] and his nationality becomes merged in his religion.” Webb continues, “If a Mohammedan, Turk, Egyptian, Syrian or African commits a crime the newspaper reports do not tell us that it was committed by a Turk, an Egyptian, a Syrian or an African, but by a Mohammedan. If an Irishman, an Italian, a Spaniard or a German commits a crime in the United States, we do not say that it was committed by a Catholic, a Methodist or a Baptist, nor even a Christian; we designate the man by his nationality. … But, just as soon as a membership of the East is arrested for a crime or misdemeanor, he is registered as a representative of the religion his parents followed or he adopted.”

In a recent debate between Reza Aslan and CNN reporters, referring back to what Aslan said to Bill Maher, Aslan argued that the monolithic representation of Islam loses its national and regional character. When Maher and reporters characterized Islam in different ways, Aslan responded “which Islam?” For instance, when asked about the treatment of women in Muslim countries, one reporter asked, “[in Muslim countries] for the most part, it is not a free and open society for women in those states.” Aslan replied, “It certainly is in Indonesia and Malaysia. It certainly is in Bangladesh. It certainly is in Turkey. I mean, again, this is the problem is that you're talking about a religion of 1.5 billion people and certainly it becomes very easy to just simply paint them all with a single brush by saying, well, in Saudi Arabia, they can't drive and so therefore that is somehow representative of Islam.”

Specifically about violence Webb asks, “If one or a dozen of these [Muslims] should commit an act of brutal intolerance or fanaticism, would it be just to say that it was due to the meritable tendencies of their religion?” His answer is very similar to Aslan’s reply when asked “if Islam promote[s] violence?” Aslan replies, “Islam is just a religion, and like every religion in the world, it depends on what you bring to it. If you're a violent person, your Islam, your Judaism, your Christianity, your Hinduism is going to be violent.”

For his part, Webb gives an early version of the repeated claim that the majority of Muslims are peaceful. Denying the statement that a Muslim goes “directly to Paradise” if he dies killing a Christian, he says, instead, this is a lie to “injure as peaceful and non-aggressive a class of people as the world has ever seen.”

This same rhetoric is not just reiterated by Aslan. The recent conversation between Bill Maher, Cornel West, and John Avalon, author of the book, Wingnuts, maintain the same tropes. After Maher continues the same wide sweeping generalizations about Islam, both his own and quoting those of others, West continues the rhetoric of internal difference, giving it his own spin. “The claim that quotes makes, the juxtaposition between liberals versus Islam, as if Islam is homogenous, there are prophetic Islamic figures who argue for liberties, for tolerance, for equality, beginning with Malcom X. Beginning with Mahmoud Mohammed Taha. There is a whole tradition within Islam that argues for rights, tolerance, and all this.”

John Avalon agrees and adds the rhetoric about peaceful Muslims, “You got to be able to confront the very real obvious threat we have been confronting as western liberal democracies for a long time while making the assumption, the clear separation between the vast majority of Muslims who are peaceful, I would argue, and a virulent strain of radical Islamism and Islamists who have been hell-bent on murdering as many people as possible for the past decade and a half.”

West rejoins, “But based on Brother Bill’s argument, the history of Christianity killing Jews, or the history of American Christians lynching black people would be the only statement for Christianity. That’s simply not true.” West’s rejoinder repeats the point that Islam being tread differently than other religions.

Recurrently we have the same rhetoric in this debate: Muslims are painted with a broad brush, the sweeping generalizations applied to Islam are not applied to other religions, we need to see that there are significant differences between different Muslims, Muslim communities, and Muslim nations, and that the majority of Muslims in the world are peaceful. This was the rhetoric for Webb at the 1893 World Parliament of Religion, and it stays the same today.

There are differences of course. The issues of polygamy in Islam, how Mohammed and his successors spread the religion by the sword, or that slavery is part of Islam, are less of an issue, but they still are discussed. Webb addressed these representations. Yet there are new ones that have emerged since Webb, often dealing with female oppression, such as female genital mutilation, to which Aslan replies, “It's a Central African problem” and not a Muslim one. Or the lack of rights women have, to which Aslan claims is only some Muslim countries, but not all. Sometimes the old issues reemerge in the new discourses about women, such as this recent essay about polygamy and women's rights in Pakistan.

While the differences are important, I find the similarities both significant and troubling. It means there really is little changing in the public debates, and the same tired points are rehashed time and again. As scholars of religion, who try to have nuance, in historical and critical conversations about these subjects, the lack of advancement regarding the public discourse about Islam is signals a larger problem. There is plenty of scholarship addressing all the points well, and push back against the generalizations on both sides. But what effect has this scholarship had on the overall discourse? Unfortunately, it seems little. This is even true for scholars like Aslan and West. Both these scholars deploy the same century-old rhetoric.

After converting to Islam, Webb addressed his fellow Theosophists, telling them of the greatness of Islam and how it had much in common with the Eastern religions they valorized. Webb went so far as to claim, “If I could take the reader by the hand and lead him along the path I have traveled … I feel assured that I could convince him that, to be a Theosophist, one must be a follower of Islam.” Theosophists rejected his claim. One replied, “But it is natural that the religion of Mohammed has not received from Western people a very great consideration. They judge it in the mass, and not from some of its teachings. The West developed its social system and its religious belief on its own lines, and having seen that many followers of the Prophet are polygamists, which is contrary to Western notions, the entire Islamic system has been condemned on that ground, both in a social and religious sense.” Today Islam is still judged as “contrary to Western notions” and “condemned on that ground, both in a social and religious sense” regardless of what scholars say. As a result, the rhetoric about Islam, over a century after Webb’s speech, is still the same.

Comments