Both Black and Catholic (?)

Matthew J. Cressler

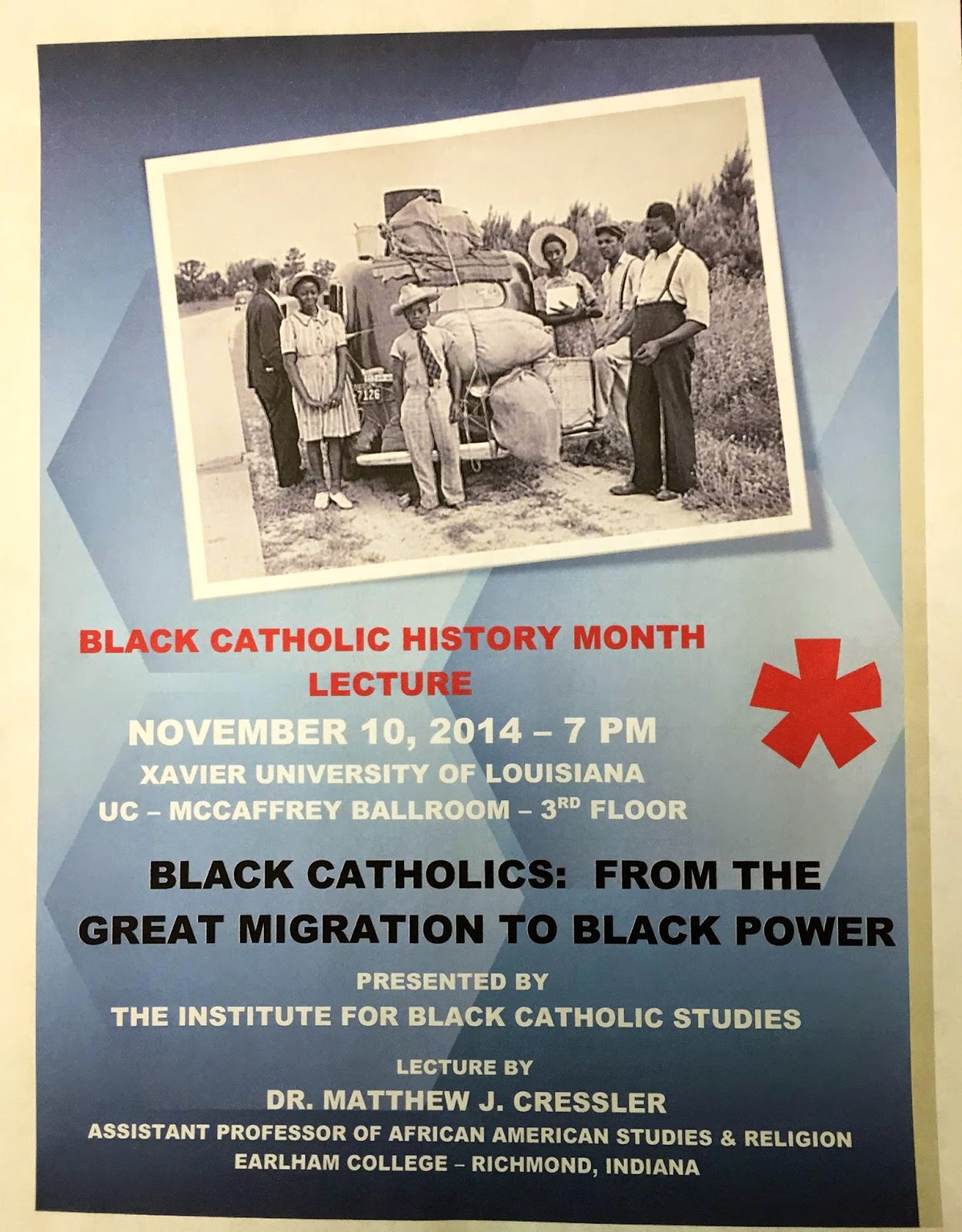

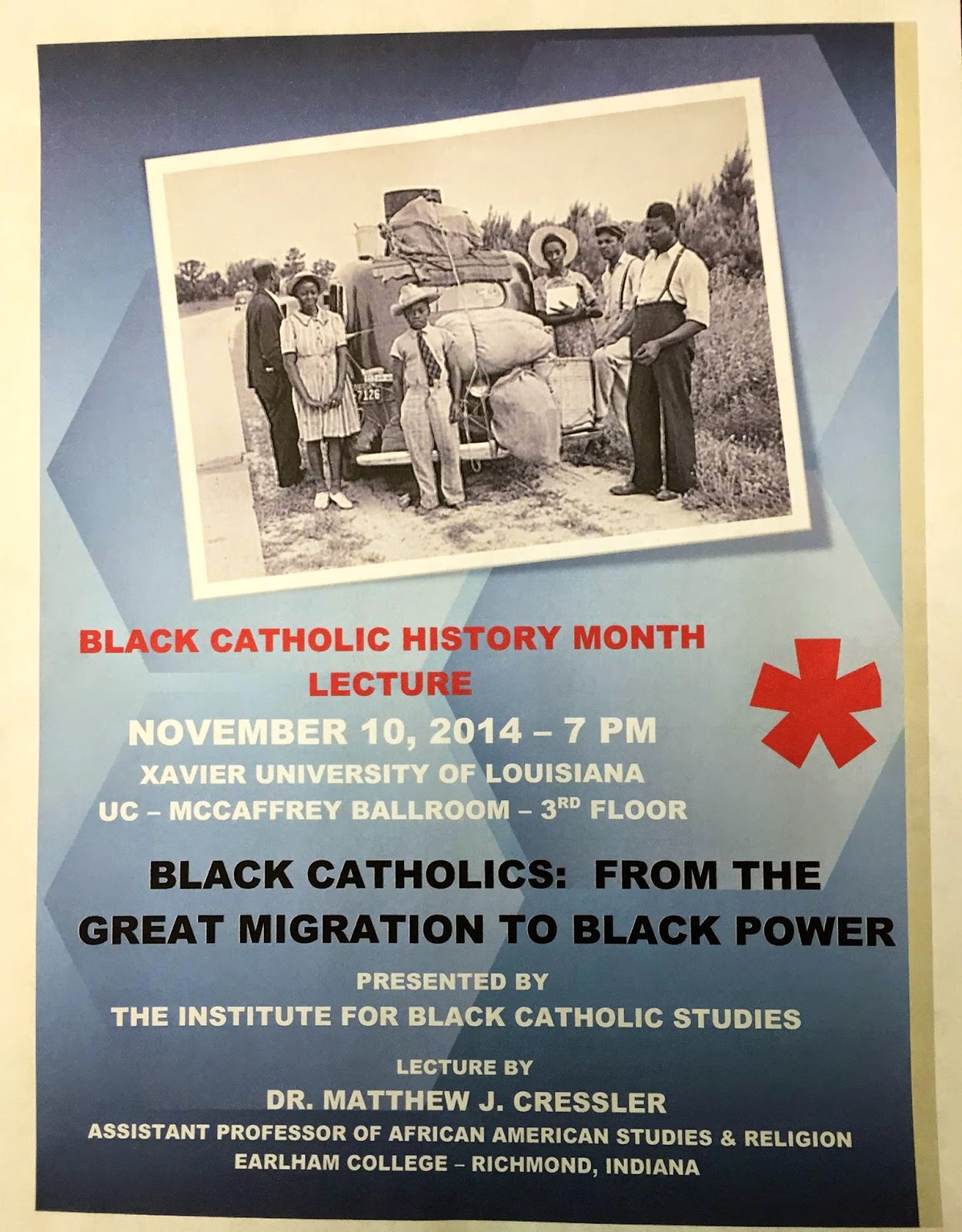

My post today falls in the "shameless plug" category. I am due to lecture at the Institute for Black Catholic Studies at Xavier University of Louisiana on Monday, November 10th. The title of my talk is "Black Catholics from the Great Migrations to Black Power," something I have thought quite a bit about for the past few years. Nevertheless (or, perhaps precisely for this reason), I've been struggling to capture the full significance of this story in just 45 minutes. So my post today offers some of the musings that have been running on repeat in the back of my mind as I prepare to share this story.

My post today falls in the "shameless plug" category. I am due to lecture at the Institute for Black Catholic Studies at Xavier University of Louisiana on Monday, November 10th. The title of my talk is "Black Catholics from the Great Migrations to Black Power," something I have thought quite a bit about for the past few years. Nevertheless (or, perhaps precisely for this reason), I've been struggling to capture the full significance of this story in just 45 minutes. So my post today offers some of the musings that have been running on repeat in the back of my mind as I prepare to share this story.

What has it meant to be both Black and Catholic in the United States? The tension between - or, better yet, the inseparability of racial and religious identities in the U.S. was felt acutely by Black Catholics in the middle years of the twentieth century. The period I have referenced in shorthand as "the Great Migrations to Black Power," roughly 1940 through 1970, was an era of unprecedented growth and transformation among Black Catholics across the United States - especially in the urban industrial centers in the North and West.

The Black Catholic population grew by 208% nationwide in these three decades and in the Midwest growth surpassed 400%. Chicago is perhaps the best example of this, rising from a few hundred people meeting in a single church at the turn of the twentieth century into a population of 80,000 people - the Archdiocese of Chicago boasted more Black Catholics than either New Orleans or Washington, D.C. by 1970, an astounding feat when one considers the long history of Black Catholic Maryland and Louisiana!

Even more remarkable than mere numbers was the dramatic - and often traumatic - transformation of Black Catholic practice and identity in this very same period. What did it mean to be both Black and Catholic? When tens of thousands of African Americans joined the Catholic Church in the 1940s and 1950s, they entered an institution renowned for its (seeming) universality and stability. Many Black converts embraced Catholic devotional habits and ritual practices that served as compelling alternatives to other ways of being Black and religious, particularly in the context of the Great Migrations when evangelical Black Christianities were becoming not only increasingly popular but also increasingly normative (what Wallace Best has called "the new sacred order of the city"). Though it could seem a little out of left field, it could said that in this way Black Catholics shared in the same impulse as Black Muslims and Black Hebrews, insofar as they positioned themselves as alternatives to and critics of "the Black Church" as traditionally conceived. When Black Catholic converts celebrated the "quiet dignity" of the Latin Mass and championed their "One True Church" in the midst of a sea of storefronts, they were insisting on a new way of being Black and religious.

And it was for precisely this reason that the religious and cultural revolutions of the late 1960s had such a traumatic impact on many Black Catholics. The Second Vatican Council initiated debates what it meant to be Catholic at the very same time that the Black Power movement presented a radical (re)interpretation of the relationship between religious and racial authenticity. As a growing number of Black Catholic priests, sisters, and laypeople rallied to the banner of Black Power and struggled to incorporate African and American American traditions into Catholic liturgical life, Black Catholic communities across the United States found themselves bitterly divided. In one sense, this division was shared by American Catholics writ large who debated amongst themselves the implications new ways of worship, conceptions of "Church," and political engagement meant for Catholic identity. But for Black Catholics in particular, it was impossible to disentangle debates over proper religious practice or political engagement from debates about racial "authenticity" and identity formation. Those who had converted to the universal and eternal "One True Church" were now told that the "quiet dignity" they had embraced was not universal at all, but white - that the Protestant practices they had rejected were not Protestant, but Black. As the 1970s opened, the question for Black Catholics was shifting from What does it mean to be both Black and Catholic in the United States? to Is it possible to be both Black and Catholic?

Perhaps, in some sense, this has always been the question - the ever-present undercurrent of Black Catholic history in the United States. Is it possible to be both Black and Catholic? This is what Albert Raboteau alluded to when he described the experience of Black Catholics in the United States as "an experience of alternating tension between the pull of universalism and the demands of racial particularism" (Fire in the Bones, 136). I will end not by answering the question, of course. Instead, I'll offer two stories from right in the middle of that Great-Migrations-to-Black-Power period I have been talking about. In 1958, a Black Catholic woman and convert wrote a series of letters from the South Side of Chicago to the head of the Franciscan Sacred Heart Province. Among the many (many) things she had to say, Mary Dolores articulated her own interpretation of the relationship between race and religion. "That kind of service you [Franciscans] render to God, through loving and serving us," Mary Dolores wrote, "lifts us up above the color line, up above the natural vicissitudes of every day life…You are restoring to us by just being Catholic a vanished dignity that all the interracial organizations together have not achieved by conference or legislation." Catholicism allowed "Negroes so called" to transcend the trappings of race altogether.

Just one year before Mary Dolores mailed her letters, Lawrence "Larry" Lucas was strolling the streets of Harlem when he ran into a formidable figure. Wearing the black suit, black tie, and white shirt uniform of a Catholic seminarian, Larry was stopped in his tracks by none other than Malcolm X. When Malcolm asked him what he was about, Larry told him he was going to school.

"I surmise that," Malcolm retorted. "What are you doing there?"

"I'm studying," Larry replied.

"That's nice, what?"

"To be a Roman Catholic priest."

Malcolm looked straight into Larry's eyes and said, quite matter-of-factly, "Are you out of your God damned mind?"

This encounter (and the others like it that followed) put Lawrence Lucas on a path that led to his becoming one of the foremost Black Catholic activists of the Black Power era. His book Black Priest / White Church: Catholics and Racism (1970) served as a manifesto of sorts for the revolution that would forever change what it meant to be both Black and Catholic in the United States. This Black Catholic Movement as it came to be known insisted (and worked to convince other Black Catholics) that the only viable - the only live option for Black Catholics was to be distinctively Catholic, to be "authentically Black" while remaining "truly Catholic."

My post today falls in the "shameless plug" category. I am due to lecture at the Institute for Black Catholic Studies at Xavier University of Louisiana on Monday, November 10th. The title of my talk is "Black Catholics from the Great Migrations to Black Power," something I have thought quite a bit about for the past few years. Nevertheless (or, perhaps precisely for this reason), I've been struggling to capture the full significance of this story in just 45 minutes. So my post today offers some of the musings that have been running on repeat in the back of my mind as I prepare to share this story.

My post today falls in the "shameless plug" category. I am due to lecture at the Institute for Black Catholic Studies at Xavier University of Louisiana on Monday, November 10th. The title of my talk is "Black Catholics from the Great Migrations to Black Power," something I have thought quite a bit about for the past few years. Nevertheless (or, perhaps precisely for this reason), I've been struggling to capture the full significance of this story in just 45 minutes. So my post today offers some of the musings that have been running on repeat in the back of my mind as I prepare to share this story.What has it meant to be both Black and Catholic in the United States? The tension between - or, better yet, the inseparability of racial and religious identities in the U.S. was felt acutely by Black Catholics in the middle years of the twentieth century. The period I have referenced in shorthand as "the Great Migrations to Black Power," roughly 1940 through 1970, was an era of unprecedented growth and transformation among Black Catholics across the United States - especially in the urban industrial centers in the North and West.

The Black Catholic population grew by 208% nationwide in these three decades and in the Midwest growth surpassed 400%. Chicago is perhaps the best example of this, rising from a few hundred people meeting in a single church at the turn of the twentieth century into a population of 80,000 people - the Archdiocese of Chicago boasted more Black Catholics than either New Orleans or Washington, D.C. by 1970, an astounding feat when one considers the long history of Black Catholic Maryland and Louisiana!

Even more remarkable than mere numbers was the dramatic - and often traumatic - transformation of Black Catholic practice and identity in this very same period. What did it mean to be both Black and Catholic? When tens of thousands of African Americans joined the Catholic Church in the 1940s and 1950s, they entered an institution renowned for its (seeming) universality and stability. Many Black converts embraced Catholic devotional habits and ritual practices that served as compelling alternatives to other ways of being Black and religious, particularly in the context of the Great Migrations when evangelical Black Christianities were becoming not only increasingly popular but also increasingly normative (what Wallace Best has called "the new sacred order of the city"). Though it could seem a little out of left field, it could said that in this way Black Catholics shared in the same impulse as Black Muslims and Black Hebrews, insofar as they positioned themselves as alternatives to and critics of "the Black Church" as traditionally conceived. When Black Catholic converts celebrated the "quiet dignity" of the Latin Mass and championed their "One True Church" in the midst of a sea of storefronts, they were insisting on a new way of being Black and religious.

And it was for precisely this reason that the religious and cultural revolutions of the late 1960s had such a traumatic impact on many Black Catholics. The Second Vatican Council initiated debates what it meant to be Catholic at the very same time that the Black Power movement presented a radical (re)interpretation of the relationship between religious and racial authenticity. As a growing number of Black Catholic priests, sisters, and laypeople rallied to the banner of Black Power and struggled to incorporate African and American American traditions into Catholic liturgical life, Black Catholic communities across the United States found themselves bitterly divided. In one sense, this division was shared by American Catholics writ large who debated amongst themselves the implications new ways of worship, conceptions of "Church," and political engagement meant for Catholic identity. But for Black Catholics in particular, it was impossible to disentangle debates over proper religious practice or political engagement from debates about racial "authenticity" and identity formation. Those who had converted to the universal and eternal "One True Church" were now told that the "quiet dignity" they had embraced was not universal at all, but white - that the Protestant practices they had rejected were not Protestant, but Black. As the 1970s opened, the question for Black Catholics was shifting from What does it mean to be both Black and Catholic in the United States? to Is it possible to be both Black and Catholic?

Perhaps, in some sense, this has always been the question - the ever-present undercurrent of Black Catholic history in the United States. Is it possible to be both Black and Catholic? This is what Albert Raboteau alluded to when he described the experience of Black Catholics in the United States as "an experience of alternating tension between the pull of universalism and the demands of racial particularism" (Fire in the Bones, 136). I will end not by answering the question, of course. Instead, I'll offer two stories from right in the middle of that Great-Migrations-to-Black-Power period I have been talking about. In 1958, a Black Catholic woman and convert wrote a series of letters from the South Side of Chicago to the head of the Franciscan Sacred Heart Province. Among the many (many) things she had to say, Mary Dolores articulated her own interpretation of the relationship between race and religion. "That kind of service you [Franciscans] render to God, through loving and serving us," Mary Dolores wrote, "lifts us up above the color line, up above the natural vicissitudes of every day life…You are restoring to us by just being Catholic a vanished dignity that all the interracial organizations together have not achieved by conference or legislation." Catholicism allowed "Negroes so called" to transcend the trappings of race altogether.

Just one year before Mary Dolores mailed her letters, Lawrence "Larry" Lucas was strolling the streets of Harlem when he ran into a formidable figure. Wearing the black suit, black tie, and white shirt uniform of a Catholic seminarian, Larry was stopped in his tracks by none other than Malcolm X. When Malcolm asked him what he was about, Larry told him he was going to school.

"I surmise that," Malcolm retorted. "What are you doing there?"

"I'm studying," Larry replied.

"That's nice, what?"

"To be a Roman Catholic priest."

Malcolm looked straight into Larry's eyes and said, quite matter-of-factly, "Are you out of your God damned mind?"

This encounter (and the others like it that followed) put Lawrence Lucas on a path that led to his becoming one of the foremost Black Catholic activists of the Black Power era. His book Black Priest / White Church: Catholics and Racism (1970) served as a manifesto of sorts for the revolution that would forever change what it meant to be both Black and Catholic in the United States. This Black Catholic Movement as it came to be known insisted (and worked to convince other Black Catholics) that the only viable - the only live option for Black Catholics was to be distinctively Catholic, to be "authentically Black" while remaining "truly Catholic."

Comments