Ben Carson, Atheism, Bibles, and the Politics of Religious Neutrality

Charles McCrary

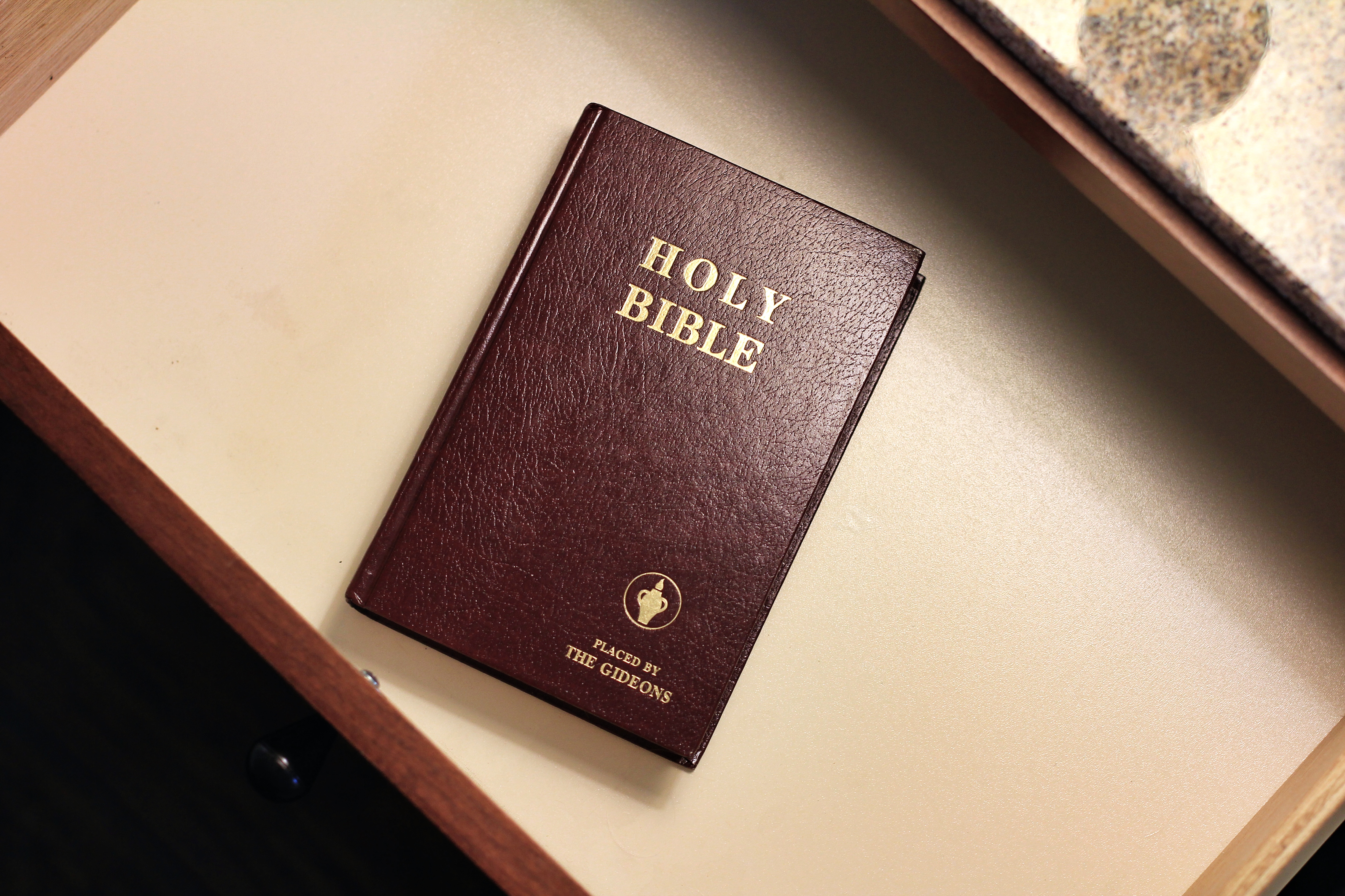

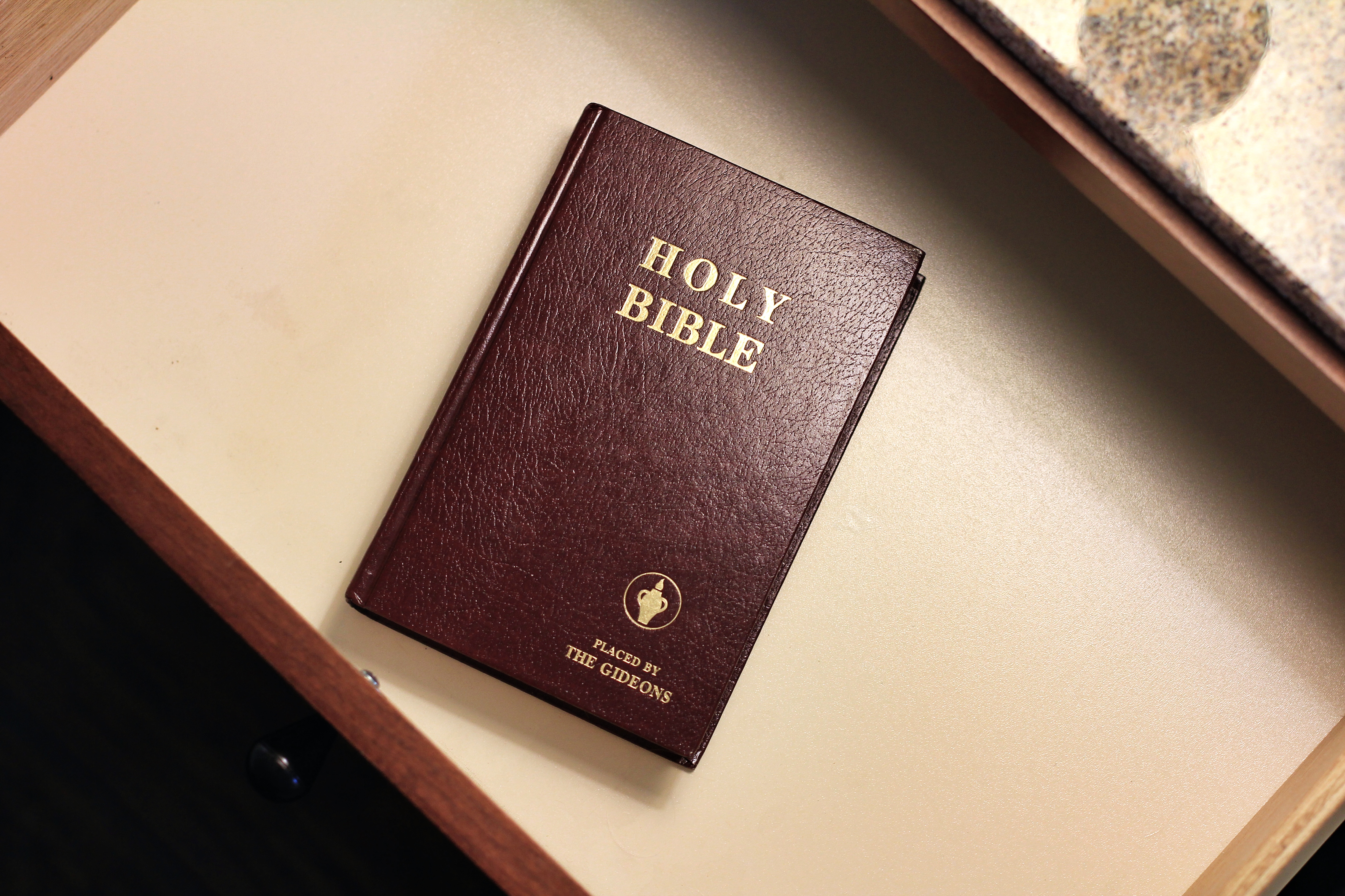

Dr. Ben Carson, a neurosurgeon, popular conservative commentator, and possible 2016 presidential candidate, recently wrote a short piece for National Review Online entitled “Atheist Absurdities.” Writing in response to the U.S. Navy’s removal of bibles from their Navy Lodge hotel rooms—a decision, prompted by pressure from the Freedom From Religion Foundation, that, prompted by pressure from other groups, including the American Family Association, they quickly reversed—Carson argues, “If they [FFRF] really thought about it, they would realize that removal of religious materials imposes their religion on everyone else.” The lack of a Bible is, ipso facto, a promotion of atheism, which, according to Carson and many others, is a religion itself. When I first read Carson’s piece, I took it as an example of how religious neutrality is becoming an impossibility—how “we are all religious now.” But I think it actually points to something different. Carson is not asserting a universality of religiosity, where there is no neutral nonreligious and the religious is constituent of our very material being. Instead, he seems to be declaring Christianity, or at least the Bible, as neutral ground. The presence of a bible, then, is equilibrium. The absence of a bible is an “infringement.”

Dr. Ben Carson, a neurosurgeon, popular conservative commentator, and possible 2016 presidential candidate, recently wrote a short piece for National Review Online entitled “Atheist Absurdities.” Writing in response to the U.S. Navy’s removal of bibles from their Navy Lodge hotel rooms—a decision, prompted by pressure from the Freedom From Religion Foundation, that, prompted by pressure from other groups, including the American Family Association, they quickly reversed—Carson argues, “If they [FFRF] really thought about it, they would realize that removal of religious materials imposes their religion on everyone else.” The lack of a Bible is, ipso facto, a promotion of atheism, which, according to Carson and many others, is a religion itself. When I first read Carson’s piece, I took it as an example of how religious neutrality is becoming an impossibility—how “we are all religious now.” But I think it actually points to something different. Carson is not asserting a universality of religiosity, where there is no neutral nonreligious and the religious is constituent of our very material being. Instead, he seems to be declaring Christianity, or at least the Bible, as neutral ground. The presence of a bible, then, is equilibrium. The absence of a bible is an “infringement.”

Like many people, including many conservative Christians, Carson argues that atheism itself is a religion, or at least something quite like it. “Is atheism a religion?” is not a question for scholars, especially historians. However, how and by whom this question is posed and answered provides excellent data. “Like traditional religions,” Carson writes, “atheism requires strong conviction,” identifying what I assume is a necessary but not sufficient condition for counting as “religion.” If atheism is indeed a religion, or at least a set of religious beliefs, then it “is extremely hypocritical of [FFRF] to request the removal of Bibles from hotel rooms…[which] imposes their religion on everyone else.” How is it, then, that by supplying a bible, the government is not showing preference to a religion?

Carson anticipates the counter-suggestion that “some atheists” (and others, I’d suspect) might make: that there should be no books in the room, but a number of texts available at the front desk, thus showing no favoritism and not offending the nonreligious. He brushes this aside with an analogy about how it would be “absurd” for hotels not to offer bottled water in the room so as not to favor one brand. “As a nation,” in the interest of pragmatic efficiency, “we must avoid the paralysis of hypersensitivity,” he advises, prescribing the distribution of “‘big boy’ pants to help the whiners learn to focus their energy in a productive way.” Flirting with self-contradiction, Carson constructs atheism and Christianity as different religions, but then, rather than saying that the Navy must necessarily favor one religion or the other, he finds a loophole. Because the Constitution guarantees freedom of religion (not from religion), Americans ought to have ample opportunity to allow “faith to guide their lives. This,” Carson concludes, “has nothing to do with imposing one’s beliefs on someone else.” Religious freedom, then, is best ensured by access to religious texts. Contra the “whiners” who might want the hotel to provide a little library, Carson seems to leave it to individuals to choose to add some religious reading to their stay. The Bible is the default option. But, if you don’t like the Bible, you have the option to ignore it, or you can bring a different book. The fact of choice, and the celebration of that fact, works to obscure the conditions of the choice.

This discussion about the politics of religious identity reminds me of a scene from the television show Louie. In one episode, Louis C.K., a comedian, is on a USO tour in Afghanistan. He tries, feebly, to chat over lunch with a fellow entertainer, a 19-year-old cheerleader. As he rambles about never really having known a cheerleader before, she interrupts him to inform him that his stand-up act is disgusting. Then she asks, “Why can’t you say Christian things and be funny?” Louie is incredulous, wondering what sort of “Christian things” she’s talking about, and how they can be funny. A minute later, when Louie shows her a duckling his daughter gave him, he refers to it as a “pretty bad-ass duckling.” The cheerleader laughs and replies, “See? You’re being Christian and funny.” Part of the humor in the scene is the apparent meaninglessness of the phrase “being Christian.” But it’s far from meaningless. What the cheerleader means by “Christian” is “not-disgusting.” In the way that “being clean” implies lack of dirt, “being Christian” in America is often identified by its absences or oppositions. “Christian,” throughout American history, has indicated a variety of negatively defined identities, including not-sinful, not-foreign, not-Catholic, not-sectarian, not-secular, etc. To be is not to be.

In this schema, the absence of Christianity is necessarily anti-Christian, whereas the presence of Christianity is neutral. This is precisely what Tracy Fessenden addressed in her seminal Culture and Redemption: “how particular forms of Protestantism emerged as an ‘unmarked category’” (6). The center constitutes itself by defining a periphery and maintaining the boundary. Only by this process, and as a product of its history, could it be intelligible to argue that the absence of a book is an “infringement” but that book’s presence is not. This is a powerful kind of emptiness.

Dr. Ben Carson, a neurosurgeon, popular conservative commentator, and possible 2016 presidential candidate, recently wrote a short piece for National Review Online entitled “Atheist Absurdities.” Writing in response to the U.S. Navy’s removal of bibles from their Navy Lodge hotel rooms—a decision, prompted by pressure from the Freedom From Religion Foundation, that, prompted by pressure from other groups, including the American Family Association, they quickly reversed—Carson argues, “If they [FFRF] really thought about it, they would realize that removal of religious materials imposes their religion on everyone else.” The lack of a Bible is, ipso facto, a promotion of atheism, which, according to Carson and many others, is a religion itself. When I first read Carson’s piece, I took it as an example of how religious neutrality is becoming an impossibility—how “we are all religious now.” But I think it actually points to something different. Carson is not asserting a universality of religiosity, where there is no neutral nonreligious and the religious is constituent of our very material being. Instead, he seems to be declaring Christianity, or at least the Bible, as neutral ground. The presence of a bible, then, is equilibrium. The absence of a bible is an “infringement.”

Dr. Ben Carson, a neurosurgeon, popular conservative commentator, and possible 2016 presidential candidate, recently wrote a short piece for National Review Online entitled “Atheist Absurdities.” Writing in response to the U.S. Navy’s removal of bibles from their Navy Lodge hotel rooms—a decision, prompted by pressure from the Freedom From Religion Foundation, that, prompted by pressure from other groups, including the American Family Association, they quickly reversed—Carson argues, “If they [FFRF] really thought about it, they would realize that removal of religious materials imposes their religion on everyone else.” The lack of a Bible is, ipso facto, a promotion of atheism, which, according to Carson and many others, is a religion itself. When I first read Carson’s piece, I took it as an example of how religious neutrality is becoming an impossibility—how “we are all religious now.” But I think it actually points to something different. Carson is not asserting a universality of religiosity, where there is no neutral nonreligious and the religious is constituent of our very material being. Instead, he seems to be declaring Christianity, or at least the Bible, as neutral ground. The presence of a bible, then, is equilibrium. The absence of a bible is an “infringement.”Like many people, including many conservative Christians, Carson argues that atheism itself is a religion, or at least something quite like it. “Is atheism a religion?” is not a question for scholars, especially historians. However, how and by whom this question is posed and answered provides excellent data. “Like traditional religions,” Carson writes, “atheism requires strong conviction,” identifying what I assume is a necessary but not sufficient condition for counting as “religion.” If atheism is indeed a religion, or at least a set of religious beliefs, then it “is extremely hypocritical of [FFRF] to request the removal of Bibles from hotel rooms…[which] imposes their religion on everyone else.” How is it, then, that by supplying a bible, the government is not showing preference to a religion?

Carson anticipates the counter-suggestion that “some atheists” (and others, I’d suspect) might make: that there should be no books in the room, but a number of texts available at the front desk, thus showing no favoritism and not offending the nonreligious. He brushes this aside with an analogy about how it would be “absurd” for hotels not to offer bottled water in the room so as not to favor one brand. “As a nation,” in the interest of pragmatic efficiency, “we must avoid the paralysis of hypersensitivity,” he advises, prescribing the distribution of “‘big boy’ pants to help the whiners learn to focus their energy in a productive way.” Flirting with self-contradiction, Carson constructs atheism and Christianity as different religions, but then, rather than saying that the Navy must necessarily favor one religion or the other, he finds a loophole. Because the Constitution guarantees freedom of religion (not from religion), Americans ought to have ample opportunity to allow “faith to guide their lives. This,” Carson concludes, “has nothing to do with imposing one’s beliefs on someone else.” Religious freedom, then, is best ensured by access to religious texts. Contra the “whiners” who might want the hotel to provide a little library, Carson seems to leave it to individuals to choose to add some religious reading to their stay. The Bible is the default option. But, if you don’t like the Bible, you have the option to ignore it, or you can bring a different book. The fact of choice, and the celebration of that fact, works to obscure the conditions of the choice.

This discussion about the politics of religious identity reminds me of a scene from the television show Louie. In one episode, Louis C.K., a comedian, is on a USO tour in Afghanistan. He tries, feebly, to chat over lunch with a fellow entertainer, a 19-year-old cheerleader. As he rambles about never really having known a cheerleader before, she interrupts him to inform him that his stand-up act is disgusting. Then she asks, “Why can’t you say Christian things and be funny?” Louie is incredulous, wondering what sort of “Christian things” she’s talking about, and how they can be funny. A minute later, when Louie shows her a duckling his daughter gave him, he refers to it as a “pretty bad-ass duckling.” The cheerleader laughs and replies, “See? You’re being Christian and funny.” Part of the humor in the scene is the apparent meaninglessness of the phrase “being Christian.” But it’s far from meaningless. What the cheerleader means by “Christian” is “not-disgusting.” In the way that “being clean” implies lack of dirt, “being Christian” in America is often identified by its absences or oppositions. “Christian,” throughout American history, has indicated a variety of negatively defined identities, including not-sinful, not-foreign, not-Catholic, not-sectarian, not-secular, etc. To be is not to be.

In this schema, the absence of Christianity is necessarily anti-Christian, whereas the presence of Christianity is neutral. This is precisely what Tracy Fessenden addressed in her seminal Culture and Redemption: “how particular forms of Protestantism emerged as an ‘unmarked category’” (6). The center constitutes itself by defining a periphery and maintaining the boundary. Only by this process, and as a product of its history, could it be intelligible to argue that the absence of a book is an “infringement” but that book’s presence is not. This is a powerful kind of emptiness.

Comments

Homer replied that this worried him, because it sounded so much like things the Nazis said about the Jews in 1930's Germany.

Not at all, said the Orangeman. There's nothing wrong with the Jews. Jews are good Protestants, like the rest of us!

So, in keeping with the theme of your piece, in Northern Ireland a Protestant is not someone who confesses to the precepts of Calvinism or Lutheranism or whatever, he's simply not a Catholic!

I'm afraid Carson didn't say that, nor is it his point.

Leaving Bibles in the room injures no one; leaving them is an evangelical act, and guaranteed under 1A as "free exercise" of religion.

The forcible removal of these Bibles is a violation of at least the spirit of 1A, and is an unnecessary aggression by what does indeed behave like a religion, that of evangelical atheism.

We do indeed need more discussion of what might constitute a genuine American religious pluralism, because yanking Bibles ain't it.

A unitarian preacher named Abbott actually tried that one in New Hampshire [Hale v. Everett, 1868]. He was no longer recognizably Christian, but claimed to be a Protestant because of his anti-Catholicism.

[He lost. Nice try, though.]

http://tinyurl.com/pc362l5