SHEAR, STEM, and Subfields

Charles McCrary

Last weekend I was in Philadelphia for the Annual Meeting of the Society for Historians of the Early American Republic (SHEAR). (See here for the program and here for Monica’s RiAH post highlighting the “religion” panels.) I presented on a panel on “Mobility and the Making on Early National Religious Idenity,” with Shari Rabin and Roy Rogers. This was my first SHEAR conference, but I doubt it will be my last. The overall quality of papers was the best of any conference I’ve attended. Friday morning’s session on “Faith, Politics, and Law After the Founding” was especially thought-provoking. Also, I attended a reception for contributors to the American Yawp, which is a great project that you should check out if you haven’t already. Anyway, SHEAR is great; you should go.

With that in mind, I want to write a little bit about the President’s Plenary, “SHEAR meets STEM,”

which focused on four categories—science, technology, engineering, and math—and

their place, meanings, and uses in the early republic. Adam

Nelson, Professor of Educational Policy Studies and History at the

University of Wisconsin–Madison, began by talking about “science” in the

context of a “global knowledge economy.” The form and function of science, he

argued, was defined and inflected by the form and function of the state. What

“scientists” (whoever they are in a given time and place) focus on has been

largely determined by what sort of research is being funded, especially by the

federal government. In the early republic, Nelson argued, American science

shifted from a more “cosmopolitan” vantage point to an emphasis on

“citizenship.” As Nelson demonstrated, almost as soon as American science had

blatantly broadcast the nationalist ideologies informing its projects, they

were obfuscated by the rhetoric of “pure,” or nonideological, science. Indeed,

this became the defining characteristic of science.

The conception of “pure” science worked, and American scientists were able to support state interests while remaining ostensibly non-ideological. For instance—to use an example I’ve written about before—American geology shifted in the 1850s away from discussing California as part of the Pacific to a more continental-based geology, emphasizing the unity of the American continent. It just so happened that in the interim, gold was discovered in California and it became a U.S. state, but nevertheless the unity of the American continent was written into its features, just as the formation of the Appalachians brought “order out of confusion.” In this way and others, the history of STEM provides not just a metaphor for but an intertwined history with American religion and politics. Science and religion, though of course sometimes in tension, often worked together toward similar ends, especially in the nineteenth century.

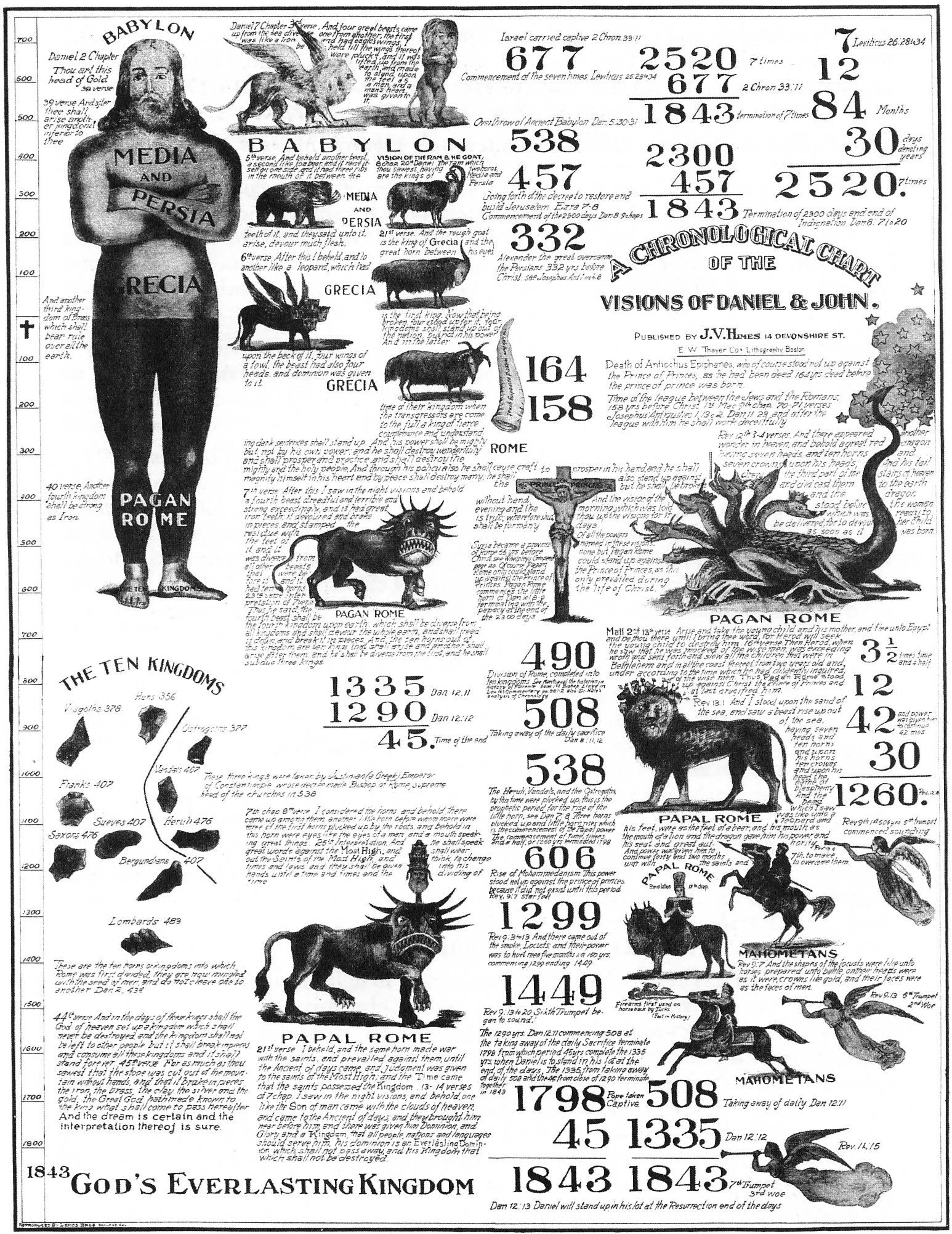

While historians of nineteenth-century American religion have focused on religious epistemology, especially “common sense realism,” much more could be done to explore broader contexts, the “global knowledge economy,” in which theologies and religious movements were reasonable. This multifaceted approach should bring more actors into our narratives. After listening to Ann Johnson’s fascinating talk on engineering, I was intrigued by the possible epistemological overlaps between Methodist circuit riders, missionaries, and governmentally funded surveyors. Caitlin Rosenthal discussed the history of math, specifically the increasing importance of numbers in nineteenth-century Americans’ lives, as evidenced by the ubiquity and indispensability of charts, such as those found in the Ready Reckoner. Discussions of biblical prophecy, Millerites, and dispensationalists, for instance, would be incomplete without recognition of this history of quantification.

Seth Rockman, in introducing the plenary panel, advised that we engage STEM—and “historicize” it. “We take things that appear to be stable and timeless and show otherwise,” he said. This is the point of doing history, regardless of our topic, whether it’s religion or science or technology. These constructions are complex process, not subject to subfield distinctions, not forged in isolation. Thus, to write histories of American religion(s), we must situate them within, or at least in relation to, other histories. That includes the histories of science, technology, engineering, and math, as well as economics, business, politics, foreign relations, and other topics too often absent from our work.

Last weekend I was in Philadelphia for the Annual Meeting of the Society for Historians of the Early American Republic (SHEAR). (See here for the program and here for Monica’s RiAH post highlighting the “religion” panels.) I presented on a panel on “Mobility and the Making on Early National Religious Idenity,” with Shari Rabin and Roy Rogers. This was my first SHEAR conference, but I doubt it will be my last. The overall quality of papers was the best of any conference I’ve attended. Friday morning’s session on “Faith, Politics, and Law After the Founding” was especially thought-provoking. Also, I attended a reception for contributors to the American Yawp, which is a great project that you should check out if you haven’t already. Anyway, SHEAR is great; you should go.

|

| A surveyor's camp |

The conception of “pure” science worked, and American scientists were able to support state interests while remaining ostensibly non-ideological. For instance—to use an example I’ve written about before—American geology shifted in the 1850s away from discussing California as part of the Pacific to a more continental-based geology, emphasizing the unity of the American continent. It just so happened that in the interim, gold was discovered in California and it became a U.S. state, but nevertheless the unity of the American continent was written into its features, just as the formation of the Appalachians brought “order out of confusion.” In this way and others, the history of STEM provides not just a metaphor for but an intertwined history with American religion and politics. Science and religion, though of course sometimes in tension, often worked together toward similar ends, especially in the nineteenth century.

While historians of nineteenth-century American religion have focused on religious epistemology, especially “common sense realism,” much more could be done to explore broader contexts, the “global knowledge economy,” in which theologies and religious movements were reasonable. This multifaceted approach should bring more actors into our narratives. After listening to Ann Johnson’s fascinating talk on engineering, I was intrigued by the possible epistemological overlaps between Methodist circuit riders, missionaries, and governmentally funded surveyors. Caitlin Rosenthal discussed the history of math, specifically the increasing importance of numbers in nineteenth-century Americans’ lives, as evidenced by the ubiquity and indispensability of charts, such as those found in the Ready Reckoner. Discussions of biblical prophecy, Millerites, and dispensationalists, for instance, would be incomplete without recognition of this history of quantification.

Seth Rockman, in introducing the plenary panel, advised that we engage STEM—and “historicize” it. “We take things that appear to be stable and timeless and show otherwise,” he said. This is the point of doing history, regardless of our topic, whether it’s religion or science or technology. These constructions are complex process, not subject to subfield distinctions, not forged in isolation. Thus, to write histories of American religion(s), we must situate them within, or at least in relation to, other histories. That includes the histories of science, technology, engineering, and math, as well as economics, business, politics, foreign relations, and other topics too often absent from our work.

Comments