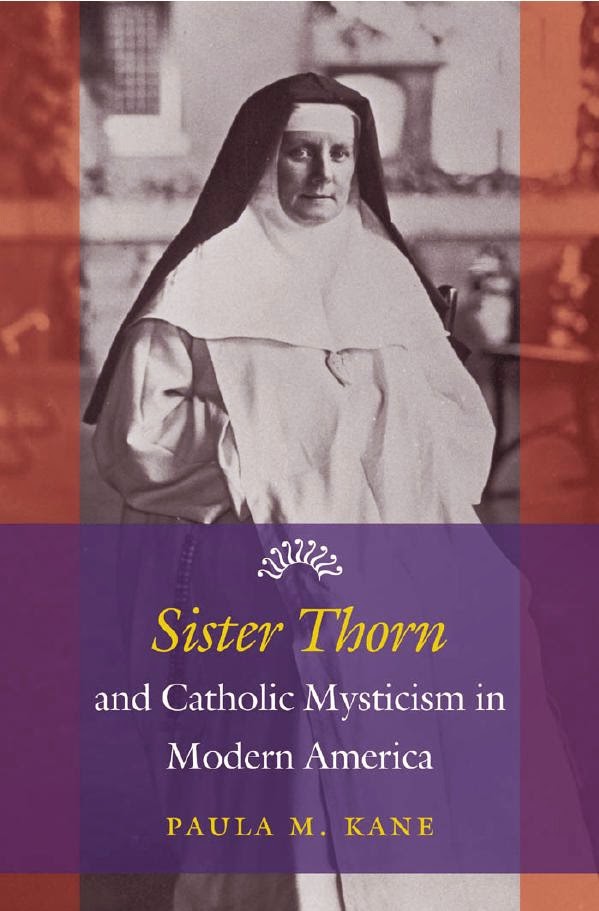

Sister Thorn and Catholic Mysticism in Modern America

I am pleased to post the following guest review of Paula Kane's Sister Thorn and Catholic Mysticism in Modern America by my friend and colleague Brian Clites. Brian is currently a doctoral candidate in American religious history at Northwestern University.

At a recent conference, a senior scholar dismissed “the lived

religion approach” by eloquently criticizing the ethnographic method. None of

the panelists (including myself) responded by stating the obvious: the study of

everyday religion is equally equipped, perhaps better so, for scholars inclined

towards anthropologically-informed history. If you don’t believe me, ask David

Hall, Leigh Eric Schmidt, or better yet Paula Kane, who has recently published

the much anticipated Sister Thorn and Catholic Mysticism in Modern America.

Kane explores the life of the forgotten American stigmatic

Margaret Reilly (1884 – 1937) to provide the backbone of this microhistorical exploration

of the oft-ignored interwar period in American Catholicism. (Reilly, in the

tradition of her chosen order, the Sisters of the Good Shepherd, took the name

Sister Mary Crown of Thorns in 1923 when she took her final vows. For a wonderful conversation about Thorn’s

biography, tune into Art Remillard’s recent

discussion with Paula Kane over on Marginalia.)

At a recent conference, a senior scholar dismissed “the lived

religion approach” by eloquently criticizing the ethnographic method. None of

the panelists (including myself) responded by stating the obvious: the study of

everyday religion is equally equipped, perhaps better so, for scholars inclined

towards anthropologically-informed history. If you don’t believe me, ask David

Hall, Leigh Eric Schmidt, or better yet Paula Kane, who has recently published

the much anticipated Sister Thorn and Catholic Mysticism in Modern America.

Kane explores the life of the forgotten American stigmatic

Margaret Reilly (1884 – 1937) to provide the backbone of this microhistorical exploration

of the oft-ignored interwar period in American Catholicism. (Reilly, in the

tradition of her chosen order, the Sisters of the Good Shepherd, took the name

Sister Mary Crown of Thorns in 1923 when she took her final vows. For a wonderful conversation about Thorn’s

biography, tune into Art Remillard’s recent

discussion with Paula Kane over on Marginalia.)

Sister Thorn is a tapestry of 7 chapters, plus an introduction and conclusion. By weaving together the patchwork of prominent individuals who influenced or interpreted Reilly’s stigmata, Kane uses a meandering stitch to connect panels that are, in their own right, all admirably erudite. Although Kane describes the flow of the book as following “roughly the chronology of Reilly’s life” (20), her analytical insights seem more in control of this narrative.

Chapters 1 and 2 explore Reilly’s “transformation” into a stigmatic nun, which allows Kane to theorize why Thorn sought penitential suffering and the work her bleeding body then did for other Catholics. Chapters 3 and 4 delve into the personal motivations of Thorn’s chief champions and critics. The final three chapters extend outward to illustrate the implications of including Sister Thorn in our grand narratives. Reilly’s craftswomanship reminds us of the importance of the sacred heart cult (Chapter 5); Thorn’s celebrity illustrates how some interwar Catholics reintegrated the pangs of immigration with the erotics of the Catholic International (Chapter 6); and devotees continued to find meaning in Thorn’s bloody wounds even as other U.S. Catholics were embarrassed by the devotionalism she emblemized (Chapter 7). Collectively, this three-pronged dossier reaffirms Kane’s thesis “that the Catholic Church used mystics like Margaret Reilly to proclaim its return to the center of Western culture after World War I” (20).

It would be disingenuous to portray this history as static or, worse, to offer such a thorough synopsis that fellow RiAH readers might be tempted to slide Sister Thorn to the side of their bookshelf. Instead, my goal is to invite dialogue by identifying two of the weightier issues I encountered in this text. First, Kane attempts an innovative, double-edged use of psychoanalysis that serves as the centerpiece of her guiding vision of Sister Thorn not only “as a provocation for Catholic historians but also as an inspiration to a new generation of scholars” who she encourages to “not abandon the powerful tools provided by critical theory developed in the 1970s and 1980s” (13).

This double-edged use of psychoanalysis is the fulcrum from which the book’s central and longest chapter pivots. The first half of Chapter 4 is a groundbreaking examination of the way Catholic medical doctors initially embraced psychoanalytical diagnoses as a way to further subjugate women’s spiritual and bodily power. The second half of the chapter quickly traverses a historiography of Freudian and post-Lacanian feminist psychoanalytical tools that might allow us to re-appropriate the very categories that were used to subjugate Reilly’s stigmatic body, particularly “hysteria,” in order to understand female victim souls as both embodied products of, and unconscious resistors to, cultural and religious subjugation. If I am reading Kane correctly, after we recognize the gendered agency of mystical suffering, we might safely admit the possibility that Sister Thorn “engineered the repetition of her own traumatic experiences” (184).

Similarly, in walking a fine tightrope between empathy and deconstructionism, Kane valorizes Reilly’s piety and devotions while thoroughly excavating the medical skepticism and scandalous accusations that ultimately thwarted Thorn’s prospects for becoming the first canonized saint of North America. Even as she explores fascinating hypotheses about the various ink supplies and devotional paraphernalia that Reilly may have used to produce the bloodstained images of the crucifix on her breast and, later, the walls of her bedroom, Kane repeatedly falls back on the Gallen letters, a set of spiteful notes that were rumored to be authored by Thorn and potentially implicate the pre-cloistered Reilly in a violent love triangle with her former physician. While I appreciate the humanity these letters bring to Sister Thorn, Kane’s reliance on the Gallen letters detracts from the otherwise persuasive evidence she harnesses.

By insisting so forcefully on the sexual desires Reilly likely shared with New York City’s working-class “charity girls,” Kane risks reducing the thorns embedded in Margaret’s forehead to a functionalist act of penitential masochism, a childish effort to “balance the score for any of her real or imagined [sexual] transgressions” (188). A second question lies in the interpretation of place. When scrutinized alongside her careful parsing of Reilly’s downtown Manhattan, Kane’s description of Peekskill reads more like a travel guide, noting for example that the Good Shepherd’s scenic acreage on the Hudson included the “Whipping Oak” which was where, “legend has it,” General George Washington reprimanded colonial deserters (65).

This contrast must be intentional, as Kane knows more about the Hudson Valley than I ever will. But certainly Mount St. Florence was more than just a an adequate antithesis to the physically- and morally-grimy convent of old E. 90th Street. Without the inferences Kane makes about the Gallen letters, the warrant that teleports Thorn’s blood to New York City begins to unravel. Similarly, I am curious whether the lived study of twentieth century American religion has now de facto uplifted the Big Apple over other significant research sites. (This, from a student of Chicago Catholicism, another fetishized city.) As with the classic works of the two authors Kane expresses the most gratitude towards – James Fisher and Robert Orsi – this book makes it difficult to imagine Thorn’s Catholic imaginary without the formative damage done by the city’s menacing skyscrapers.

In summary, by exquisitely reconstructing Reilly’s New York City, Kane puts the study of American Catholicism into conversation with a transnational history of victim souls from the sixteenth- to the twenty-first century. Along the way, she offers several answers to her initial question, “How did a stigmatic help ordinary Catholic understand themselves as fully modern Americans?” (6). Over the fifteen years devoted to this research, Kane travelled to archives on two continents, interviewed Reilly’s relatives, and became fluent in topics that most of us rarely contend with, including “dermatology, hematology, and oncology” (11). Her innovative approach to anthropologically-informed history allowed methodological techniques as diverse as sleeping under Sister Thorn’s white woolen shawls at the Jamaica-Queens convent and scouring Italian YouTube videos. The resulting monograph is breathtaking. As much for its methodology as for its conclusions, Sister Thorn seems likely to become standard reading for students of American religious history.

At a recent conference, a senior scholar dismissed “the lived

religion approach” by eloquently criticizing the ethnographic method. None of

the panelists (including myself) responded by stating the obvious: the study of

everyday religion is equally equipped, perhaps better so, for scholars inclined

towards anthropologically-informed history. If you don’t believe me, ask David

Hall, Leigh Eric Schmidt, or better yet Paula Kane, who has recently published

the much anticipated Sister Thorn and Catholic Mysticism in Modern America.

Kane explores the life of the forgotten American stigmatic

Margaret Reilly (1884 – 1937) to provide the backbone of this microhistorical exploration

of the oft-ignored interwar period in American Catholicism. (Reilly, in the

tradition of her chosen order, the Sisters of the Good Shepherd, took the name

Sister Mary Crown of Thorns in 1923 when she took her final vows. For a wonderful conversation about Thorn’s

biography, tune into Art Remillard’s recent

discussion with Paula Kane over on Marginalia.)

At a recent conference, a senior scholar dismissed “the lived

religion approach” by eloquently criticizing the ethnographic method. None of

the panelists (including myself) responded by stating the obvious: the study of

everyday religion is equally equipped, perhaps better so, for scholars inclined

towards anthropologically-informed history. If you don’t believe me, ask David

Hall, Leigh Eric Schmidt, or better yet Paula Kane, who has recently published

the much anticipated Sister Thorn and Catholic Mysticism in Modern America.

Kane explores the life of the forgotten American stigmatic

Margaret Reilly (1884 – 1937) to provide the backbone of this microhistorical exploration

of the oft-ignored interwar period in American Catholicism. (Reilly, in the

tradition of her chosen order, the Sisters of the Good Shepherd, took the name

Sister Mary Crown of Thorns in 1923 when she took her final vows. For a wonderful conversation about Thorn’s

biography, tune into Art Remillard’s recent

discussion with Paula Kane over on Marginalia.)

Sister Thorn is a tapestry of 7 chapters, plus an introduction and conclusion. By weaving together the patchwork of prominent individuals who influenced or interpreted Reilly’s stigmata, Kane uses a meandering stitch to connect panels that are, in their own right, all admirably erudite. Although Kane describes the flow of the book as following “roughly the chronology of Reilly’s life” (20), her analytical insights seem more in control of this narrative.

Chapters 1 and 2 explore Reilly’s “transformation” into a stigmatic nun, which allows Kane to theorize why Thorn sought penitential suffering and the work her bleeding body then did for other Catholics. Chapters 3 and 4 delve into the personal motivations of Thorn’s chief champions and critics. The final three chapters extend outward to illustrate the implications of including Sister Thorn in our grand narratives. Reilly’s craftswomanship reminds us of the importance of the sacred heart cult (Chapter 5); Thorn’s celebrity illustrates how some interwar Catholics reintegrated the pangs of immigration with the erotics of the Catholic International (Chapter 6); and devotees continued to find meaning in Thorn’s bloody wounds even as other U.S. Catholics were embarrassed by the devotionalism she emblemized (Chapter 7). Collectively, this three-pronged dossier reaffirms Kane’s thesis “that the Catholic Church used mystics like Margaret Reilly to proclaim its return to the center of Western culture after World War I” (20).

It would be disingenuous to portray this history as static or, worse, to offer such a thorough synopsis that fellow RiAH readers might be tempted to slide Sister Thorn to the side of their bookshelf. Instead, my goal is to invite dialogue by identifying two of the weightier issues I encountered in this text. First, Kane attempts an innovative, double-edged use of psychoanalysis that serves as the centerpiece of her guiding vision of Sister Thorn not only “as a provocation for Catholic historians but also as an inspiration to a new generation of scholars” who she encourages to “not abandon the powerful tools provided by critical theory developed in the 1970s and 1980s” (13).

This double-edged use of psychoanalysis is the fulcrum from which the book’s central and longest chapter pivots. The first half of Chapter 4 is a groundbreaking examination of the way Catholic medical doctors initially embraced psychoanalytical diagnoses as a way to further subjugate women’s spiritual and bodily power. The second half of the chapter quickly traverses a historiography of Freudian and post-Lacanian feminist psychoanalytical tools that might allow us to re-appropriate the very categories that were used to subjugate Reilly’s stigmatic body, particularly “hysteria,” in order to understand female victim souls as both embodied products of, and unconscious resistors to, cultural and religious subjugation. If I am reading Kane correctly, after we recognize the gendered agency of mystical suffering, we might safely admit the possibility that Sister Thorn “engineered the repetition of her own traumatic experiences” (184).

Similarly, in walking a fine tightrope between empathy and deconstructionism, Kane valorizes Reilly’s piety and devotions while thoroughly excavating the medical skepticism and scandalous accusations that ultimately thwarted Thorn’s prospects for becoming the first canonized saint of North America. Even as she explores fascinating hypotheses about the various ink supplies and devotional paraphernalia that Reilly may have used to produce the bloodstained images of the crucifix on her breast and, later, the walls of her bedroom, Kane repeatedly falls back on the Gallen letters, a set of spiteful notes that were rumored to be authored by Thorn and potentially implicate the pre-cloistered Reilly in a violent love triangle with her former physician. While I appreciate the humanity these letters bring to Sister Thorn, Kane’s reliance on the Gallen letters detracts from the otherwise persuasive evidence she harnesses.

By insisting so forcefully on the sexual desires Reilly likely shared with New York City’s working-class “charity girls,” Kane risks reducing the thorns embedded in Margaret’s forehead to a functionalist act of penitential masochism, a childish effort to “balance the score for any of her real or imagined [sexual] transgressions” (188). A second question lies in the interpretation of place. When scrutinized alongside her careful parsing of Reilly’s downtown Manhattan, Kane’s description of Peekskill reads more like a travel guide, noting for example that the Good Shepherd’s scenic acreage on the Hudson included the “Whipping Oak” which was where, “legend has it,” General George Washington reprimanded colonial deserters (65).

This contrast must be intentional, as Kane knows more about the Hudson Valley than I ever will. But certainly Mount St. Florence was more than just a an adequate antithesis to the physically- and morally-grimy convent of old E. 90th Street. Without the inferences Kane makes about the Gallen letters, the warrant that teleports Thorn’s blood to New York City begins to unravel. Similarly, I am curious whether the lived study of twentieth century American religion has now de facto uplifted the Big Apple over other significant research sites. (This, from a student of Chicago Catholicism, another fetishized city.) As with the classic works of the two authors Kane expresses the most gratitude towards – James Fisher and Robert Orsi – this book makes it difficult to imagine Thorn’s Catholic imaginary without the formative damage done by the city’s menacing skyscrapers.

In summary, by exquisitely reconstructing Reilly’s New York City, Kane puts the study of American Catholicism into conversation with a transnational history of victim souls from the sixteenth- to the twenty-first century. Along the way, she offers several answers to her initial question, “How did a stigmatic help ordinary Catholic understand themselves as fully modern Americans?” (6). Over the fifteen years devoted to this research, Kane travelled to archives on two continents, interviewed Reilly’s relatives, and became fluent in topics that most of us rarely contend with, including “dermatology, hematology, and oncology” (11). Her innovative approach to anthropologically-informed history allowed methodological techniques as diverse as sleeping under Sister Thorn’s white woolen shawls at the Jamaica-Queens convent and scouring Italian YouTube videos. The resulting monograph is breathtaking. As much for its methodology as for its conclusions, Sister Thorn seems likely to become standard reading for students of American religious history.

Comments