Crowdsourcing the Collections: Introducing the Jesuit Libraries Provenance Project

I'm thrilled to host another guest post from two scholars at Loyola University working at the intersection of religious history, public history, and digital history. Kyle Roberts, Assistant Professor of Public History and New Media at Loyola University Chicago is the Project Director of the Jesuit Libraries Project and the Jesuit Libraries Provenance Project. He's shared with us the progress of his efforts to recreate the bibliographic world Catholic higher education. This time, he's joined by Joshua Arens, a master’s candidate in Public History at Loyola, who is the Project Coordinator for the new Jesuit Libraries Provenance Project.

Kyle Roberts and Joshua Arens

Over the course of the fall semester, sixteen graduate students in the Digital Humanities, History, and Public History Programs at Loyola University Chicago created a virtual library system out of the original (c.1878) manuscript library catalogue for St Ignatius College (Loyola’s precursor). (For more on the Jesuit Libraries Project, see this RIAH blog post from last September). Researching and reconstructing the 5200+ titles in the library catalogue raised fascinating questions about the intellectual and spiritual life of the young Jesuit college. (To learn more about the students’ preliminary answers to these questions, check out the videos of their final presentations). The students’ work also revealed that an impressive number of original library books still survive in the university libraries’ collections.

Frankly, no one had any idea at the start of the Jesuit Libraries Project how many original library books might survive. The question was frequently asked, but there were too many other tasks to complete and no time to come up with an informed estimate. The question came to the fore once again in late September as the students quickly realized when harvesting MARC records that the more surviving books they found in Loyola’s online library catalogue the less guesswork they would have to do on Worldcat. As students shared the results of their first passes at researching their segment of the catalogue it became apparent that a substantial number had survived. By the end of the semester we realized that perhaps over a third (1750/5200) of the original books might still survive in the university libraries’ collections today. Why is this surprising? Primarily because the reconstruction of the catalogue revealed that the vast majority of the books that the Jesuits collected were inexpensive mid-nineteenth-century books – i.e. books mass-produced on that highly acidic, and now brittle paper familiar to all who work on the period. After 140 years of hard use, many should have been lost of disintegrated.

There wasn’t time for the students in the fall course to track down all of these original books, which the

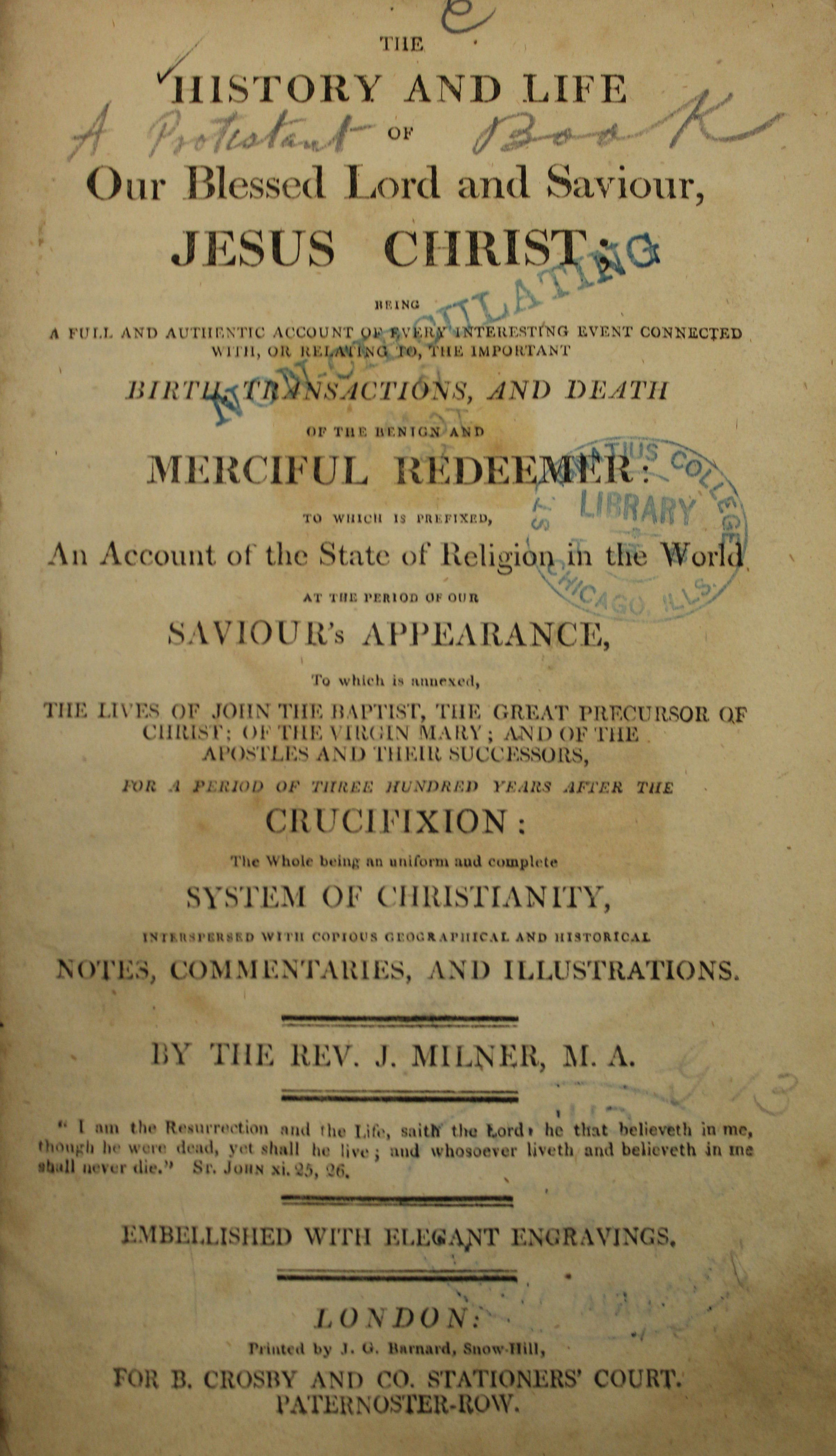

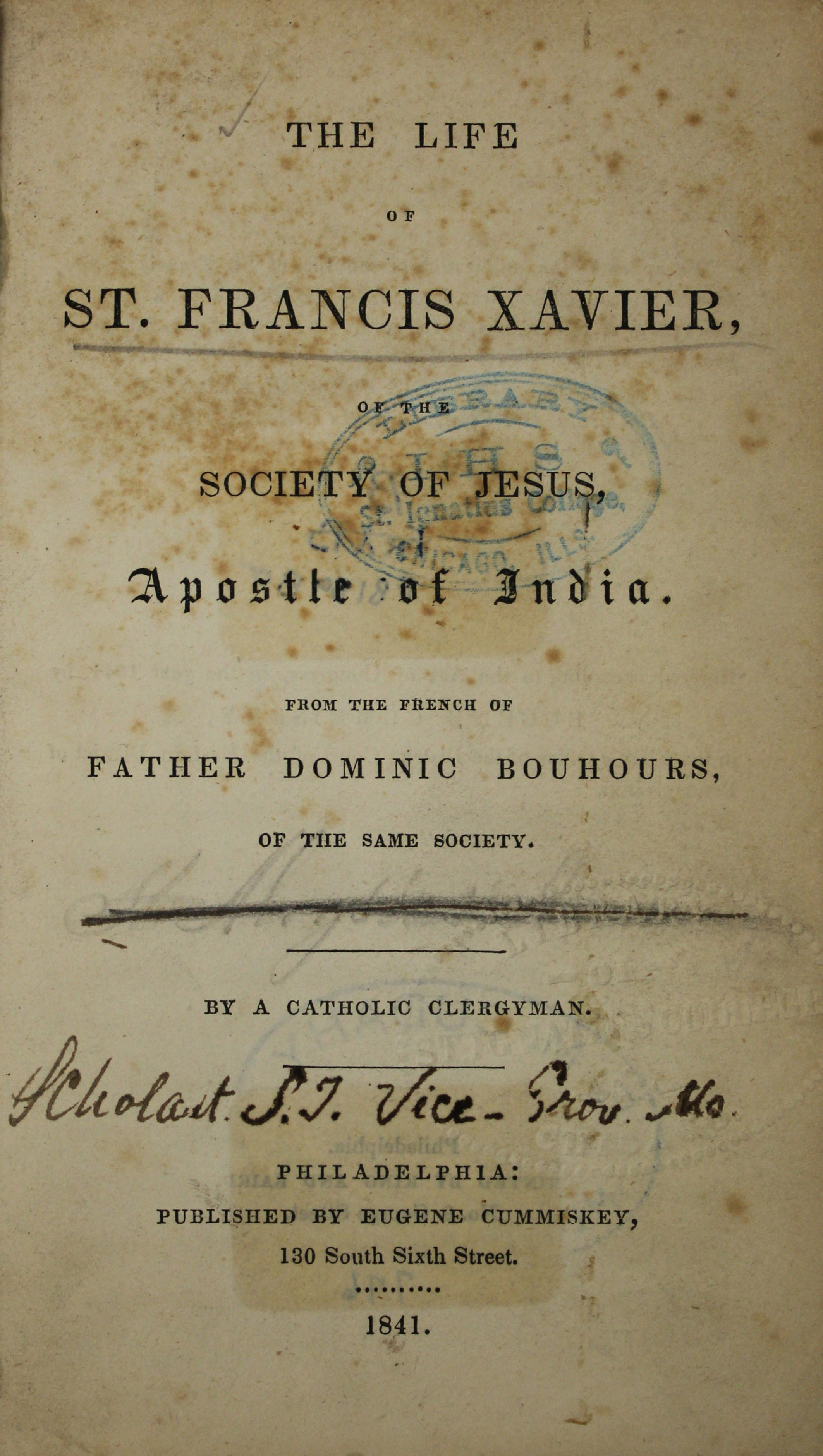

online catalogue claimed were scattered throughout Special Collections, the Library Storage Facility, the main stacks of Cudahy Library, and, most intriguingly, in the library of Loyola’s Rome Campus. (Several students generously volunteered to track the Rome books down if funds became available!) As the semester wrapped up, we were left with a long list of surviving books and an itching desire to figure out more about them. A trip down into the Library Storage Facility – where many perfectly good old books that haven’t been borrowed in a while go to hide out – revealed that several original library books had intriguing ownership marks, fascinating bindings, and even tipped in materials, such as prayer cards and a green silk ribbon cross with a dried four-leaf clover (in a French Marian devotional!). While the virtual library system could reveal what books the Jesuits had acquired, these surviving books could tell us where these books had come from and how they were used!

We knew there was a plethora of information to be recovered from these surviving books, but we also knew we needed three things in order to extract it: a research process, a platform for sharing our discoveries, and a team to undertake the work. The second of the three requirements actually came first. Impressed by the success of the Penn Provenance Project and the Ransom Center’s Medieval Fragments Project in sharing collections and crowd sourcing identifications and transcriptions, we figured we might build off their success using Flickr, the social media image-sharing platform, as an online visual archive. As a popular social media site, Flickr has fostered a participatory culture of information sharing. If there are people out there willing to “favorite” inscriptions in books owned by Penn and translate binding waste in Medieval books at the Ransom Center, we thought, surely there must be students and scholars, collectors and Catholics that would be intrigued by the holdings of a nineteenth-century Jesuit college.

Our team was soon joined by two more: undergraduate interns Sarah Muenzer and Evan Thompson. Sarah is a senior History Honors student who having “rediscovered” the 1751 and 1764 Currency Acts in an Honors research paper wanted to try her hand at rediscovering some other primary sources. Sarah’s blog provides wonderful insights into her experience of the project. Evan is a junior History major, Catholic Studies minor, who has been working on the Jesuit Libraries Project for over a year now. Generous funding from Loyola’s Hank Center for the Catholic Intellectual Heritage meant that we could actually provide Sarah and Evan with a stipend for their work.

With a platform and a team, we just needed a research process. In January, we began by tracking down approximately 200 books that the online catalogue claimed were still circulating in Cudahy Library, Loyola’s main library. As it turned out, about 30 of these books were either missing or had bookplates from other libraries (and hence would have been acquired by Loyola in the late twentieth century). The next step was to photograph the title pages and ownership marks within these books, as well as illustrations, marginalia, unusual covers, and bindings. Finally, we created a system for organizing, describing, and tagging the books in Flickr. Visitors (of which we hope you will be one) to the Jesuit Libraries Provenance Project Flickr site can:

On March 8th, the Jesuit Libraries Provenance Project launched with 25 books and 97 images. With 1725 books to go, there will be new uploads every week (with the occasional holiday break). If you don’t have a Flickr account, signing up takes about a minute. You can view all of our images without an account, but “commenting” and other user activities require a Yahoo! Account. (Note: Since Flickr is powered by Yahoo!, if you already have a Yahoo! account you already have a Flickr account). We have found that Google Chrome, Safari, or Mozilla Foxfire tend to work best for Flickr viewing. To learn more or to follow our progress, we hope you will follow our Blog, Facebook, and Twitter pages.

Our long-term goal is for the Flickr site to be an expansive platform that would incorporate images from other Jesuit schools, colleges, and universities. Given the nature of nineteenth-century settlement patterns, we strongly suspect that similar bookplates, labels, inscriptions, stamps, and other ownership marks might be found across these collections. Through Flickr we have the ability to digitally re-unite dispersed collections. Join us!

Kyle Roberts and Joshua Arens

Over the course of the fall semester, sixteen graduate students in the Digital Humanities, History, and Public History Programs at Loyola University Chicago created a virtual library system out of the original (c.1878) manuscript library catalogue for St Ignatius College (Loyola’s precursor). (For more on the Jesuit Libraries Project, see this RIAH blog post from last September). Researching and reconstructing the 5200+ titles in the library catalogue raised fascinating questions about the intellectual and spiritual life of the young Jesuit college. (To learn more about the students’ preliminary answers to these questions, check out the videos of their final presentations). The students’ work also revealed that an impressive number of original library books still survive in the university libraries’ collections.

Frankly, no one had any idea at the start of the Jesuit Libraries Project how many original library books might survive. The question was frequently asked, but there were too many other tasks to complete and no time to come up with an informed estimate. The question came to the fore once again in late September as the students quickly realized when harvesting MARC records that the more surviving books they found in Loyola’s online library catalogue the less guesswork they would have to do on Worldcat. As students shared the results of their first passes at researching their segment of the catalogue it became apparent that a substantial number had survived. By the end of the semester we realized that perhaps over a third (1750/5200) of the original books might still survive in the university libraries’ collections today. Why is this surprising? Primarily because the reconstruction of the catalogue revealed that the vast majority of the books that the Jesuits collected were inexpensive mid-nineteenth-century books – i.e. books mass-produced on that highly acidic, and now brittle paper familiar to all who work on the period. After 140 years of hard use, many should have been lost of disintegrated.

There wasn’t time for the students in the fall course to track down all of these original books, which the

online catalogue claimed were scattered throughout Special Collections, the Library Storage Facility, the main stacks of Cudahy Library, and, most intriguingly, in the library of Loyola’s Rome Campus. (Several students generously volunteered to track the Rome books down if funds became available!) As the semester wrapped up, we were left with a long list of surviving books and an itching desire to figure out more about them. A trip down into the Library Storage Facility – where many perfectly good old books that haven’t been borrowed in a while go to hide out – revealed that several original library books had intriguing ownership marks, fascinating bindings, and even tipped in materials, such as prayer cards and a green silk ribbon cross with a dried four-leaf clover (in a French Marian devotional!). While the virtual library system could reveal what books the Jesuits had acquired, these surviving books could tell us where these books had come from and how they were used!

We knew there was a plethora of information to be recovered from these surviving books, but we also knew we needed three things in order to extract it: a research process, a platform for sharing our discoveries, and a team to undertake the work. The second of the three requirements actually came first. Impressed by the success of the Penn Provenance Project and the Ransom Center’s Medieval Fragments Project in sharing collections and crowd sourcing identifications and transcriptions, we figured we might build off their success using Flickr, the social media image-sharing platform, as an online visual archive. As a popular social media site, Flickr has fostered a participatory culture of information sharing. If there are people out there willing to “favorite” inscriptions in books owned by Penn and translate binding waste in Medieval books at the Ransom Center, we thought, surely there must be students and scholars, collectors and Catholics that would be intrigued by the holdings of a nineteenth-century Jesuit college.

With a platform and a team, we just needed a research process. In January, we began by tracking down approximately 200 books that the online catalogue claimed were still circulating in Cudahy Library, Loyola’s main library. As it turned out, about 30 of these books were either missing or had bookplates from other libraries (and hence would have been acquired by Loyola in the late twentieth century). The next step was to photograph the title pages and ownership marks within these books, as well as illustrations, marginalia, unusual covers, and bindings. Finally, we created a system for organizing, describing, and tagging the books in Flickr. Visitors (of which we hope you will be one) to the Jesuit Libraries Provenance Project Flickr site can:

- Browse our photostream and look at individual images: each uploaded image includes a bibliographic description as well as a number of “tags” that you can use to find similar images;

- Explore “sets” with an eye towards particular research questions: images are identified and placed in sets by subject (i.e. theology, history) and types of ownership marks (i.e. inscription, label). Most ownership marks are further separated by “identified” or “unidentified” based on whether or not the mark of provenance in the photograph has been identified;

- Contribute your own expertise: We hope users will make use of the “commenting” function on Flickr to share any knowledge they might have about these books, their ownership marks, or their subject matter. Any information puts us one step closer towards uncovering the history of that particular book and the history of St. Ignatius College’s original library.

On March 8th, the Jesuit Libraries Provenance Project launched with 25 books and 97 images. With 1725 books to go, there will be new uploads every week (with the occasional holiday break). If you don’t have a Flickr account, signing up takes about a minute. You can view all of our images without an account, but “commenting” and other user activities require a Yahoo! Account. (Note: Since Flickr is powered by Yahoo!, if you already have a Yahoo! account you already have a Flickr account). We have found that Google Chrome, Safari, or Mozilla Foxfire tend to work best for Flickr viewing. To learn more or to follow our progress, we hope you will follow our Blog, Facebook, and Twitter pages.

Our long-term goal is for the Flickr site to be an expansive platform that would incorporate images from other Jesuit schools, colleges, and universities. Given the nature of nineteenth-century settlement patterns, we strongly suspect that similar bookplates, labels, inscriptions, stamps, and other ownership marks might be found across these collections. Through Flickr we have the ability to digitally re-unite dispersed collections. Join us!

Comments

I'm really excited to compare the images with my research once I get my dissertation draft off my desk.