Politics of Representation--Between Critic and Classroom

Rachel Lindsey

In a recent essay in Religion and Politics, I categorized last year's film 12 Years a Slave as a "political act" that, among other things, "present[s] religion as a mechanism of the film's political efforts."

The movie (which Charity R. Carney reviewed on this blog in November) has succeeded in sparking a number of conversations about race through the catalyzing legacies of American enslavement. And yet conversation is not nearly capacious enough a category for defining the political. Visual and cinematic strategies are integral to the film's politics, but focusing attention on the cinematic success of 12 Years a Slave also works to contain the problems that the film ostensibly exposes. Focusing attention on the movie's treatment of historical slavery does not let us off the hook for ignoring the racism that continues to immobilize Atlanta or the crippling segregation of St. Louis. So the questions I am left with are not far from those with which I started--what is this film about? What are we to do?

I'm not going to recap the essay here (you're welcome). But I do want to raise the question of the film's treatment of religion to this audience by way of the continuity (or disjuncture) between cultural critique and classroom pedagogy.

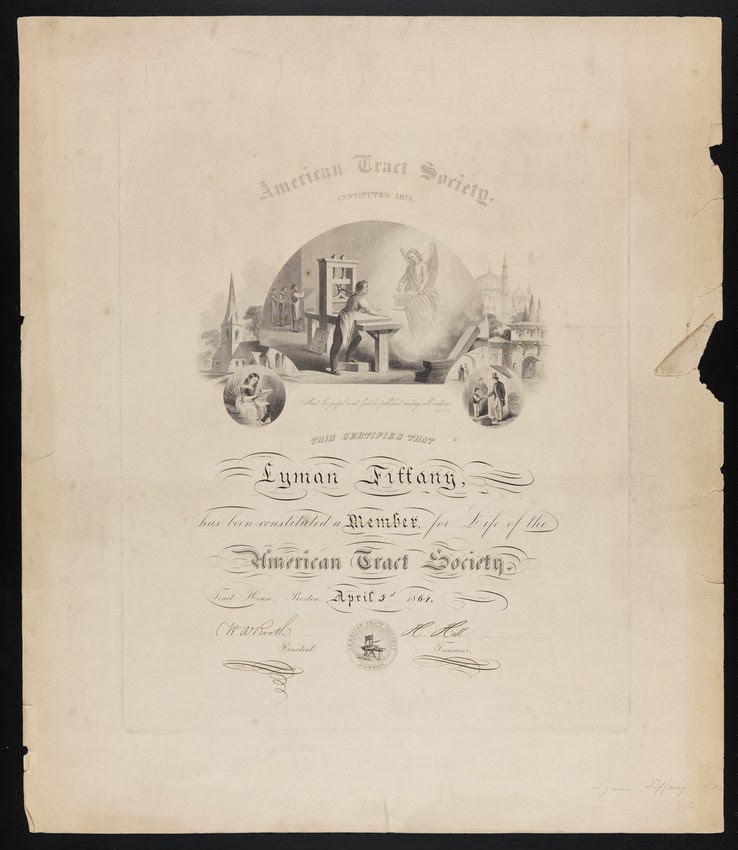

In prepping and teaching a course on representation and religion I've been thinking a lot about the swirl of religion, technology, and politics in American history and this film strikes me as an important instance of this long entanglement. The film, as Armond White recognized--shall we say, colorfully--early after its release, is not history. Still, both the book (published in the 1850s) and the movie (released in 2013) are wrapped up in the technologies and related strategies of representation of their historical moments--and certainly this has to count for something. Historical accuracy is certainly one measure of success. But metrics of precision, not to mention definitions of history, have hardly been stable. American culture has long been far more populated with media and mechanisms that have been more concerned with charting boundaries of belonging and exclusion than with capitulating to standards of empirical scholarship. As David Morgan, Judith Weisenfeld, Leigh Schmidt, Sally Promey, and many others have demonstrated, technologies have long been integral to the ways Americans have represented, structured, and experienced their lives--the iconography of the printing press in American Tract Society lifetime memberships throughout the nineteenth-century is just one example among countless others. 12 Years a Slave does not stand apart from this history of technologically-mediated representation but it may shed light on its relevance to our own historical moment.

In a recent essay in Religion and Politics, I categorized last year's film 12 Years a Slave as a "political act" that, among other things, "present[s] religion as a mechanism of the film's political efforts."

The movie (which Charity R. Carney reviewed on this blog in November) has succeeded in sparking a number of conversations about race through the catalyzing legacies of American enslavement. And yet conversation is not nearly capacious enough a category for defining the political. Visual and cinematic strategies are integral to the film's politics, but focusing attention on the cinematic success of 12 Years a Slave also works to contain the problems that the film ostensibly exposes. Focusing attention on the movie's treatment of historical slavery does not let us off the hook for ignoring the racism that continues to immobilize Atlanta or the crippling segregation of St. Louis. So the questions I am left with are not far from those with which I started--what is this film about? What are we to do?

I'm not going to recap the essay here (you're welcome). But I do want to raise the question of the film's treatment of religion to this audience by way of the continuity (or disjuncture) between cultural critique and classroom pedagogy.

|

| American Tract Society Membership Certificate. Historic New England. |

Comments