A Super(natural) Bowl?

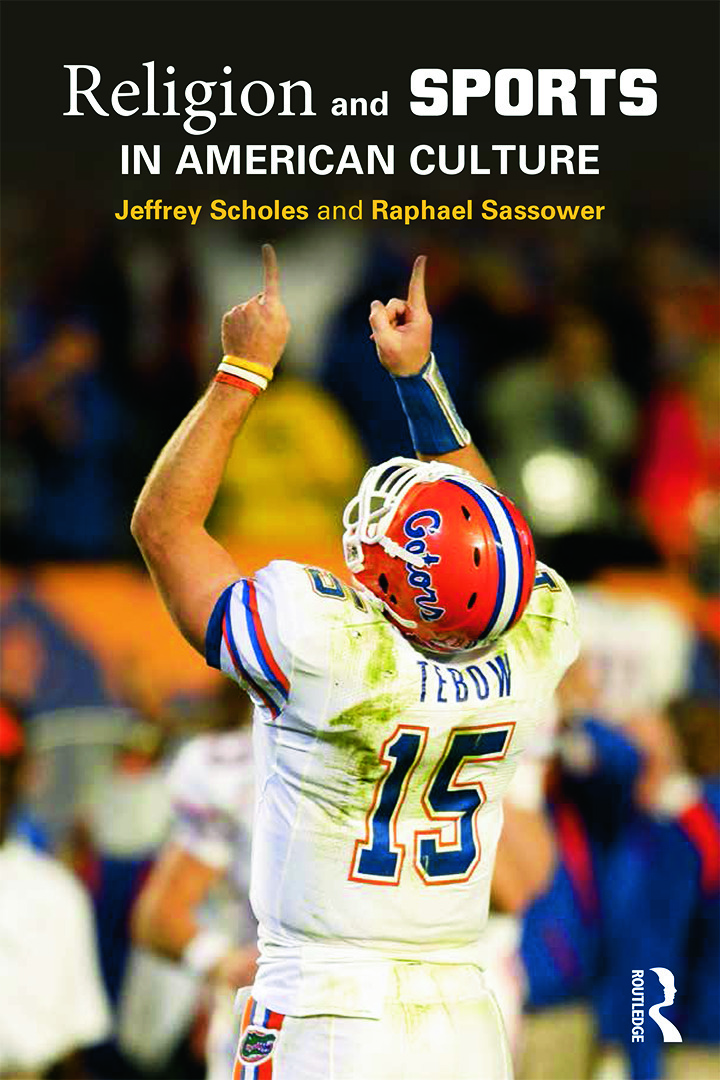

I'm pleased to guest post this from my two colleagues down the hall from me, Jeffrey Scholes (who previously posted here after his beloved Rangers just missed winning the World Series a couple of years back) and Raphael Sassower, from the Philosophy Department at the University of Colorado. They are the co-authors of a brand new book just out with from Routledge, Religion and Sports in American Culture. The eyes of Tebow, or of Richard Sherman, are upon you.

Jeffrey Scholes and Raphael Sassower

Jeffrey Scholes and Raphael SassowerThe headline of a survey released by the Public Religion Research Institute in mid-January “Half of American Fans See Supernatural forces at Play in Sports,” was sure to catch some attention. Eyes must have rolled at the ridiculous suggestion of God intervening in an event that has millionaires running around, trying to catch a piece of leather. Reggie White was either confused or calculated when he claimed that God told him to play for the Green Bay Packers. Yet some nod approvingly at that headline— of course God listens to prayers and is involved in all of creation, so there must be supernatural forces at work on a football field. In between these two sets of reactions is a larger group that may not be willing to drag the divine down into the dirt of a playing field yet refuse to restrict the divine from doing so.

Knowing that theologically crass questions, such as the one asked on the

pre-Super Bowl 2013 edition of Sports

Illustrated “Does God Care Who Wins the Super Bowl?” generate a range of

emotions (that in turn generate magazine sales), we shouldn’t be surprised that

the relationship between religion and sports elicits one’s own theology.

The unlikely rise of vocal Christian,

and then Denver Bronco, Tim Tebow, evoked a range of reactions two years ago

heretofore unseen. From David Brooks’ assertion

that the relationship between religion and sports comes down to the values that

are honored in players and fans alike to Chuck Klosterman’s claim that

Tebow “makes blind faith a viable option,” we see that removing religion

altogether from sports (as Ross Douthat’s “sophisticated Christian” attempts

to do) is difficult even for the hardened skeptic. Wherever you look, religious

ideals and practices find expression in all cultural phenomena, though we are

limiting ourselves to sports here.

More

to the point, a closer look at the PRRI survey tells a different story than the

one manufactured by Sports Illustrated. What leads the compiler of the evidence to

deduce that a majority of Americans believe that “supernatural forces” are

involved in sports? One, a sizeable percentage (25% of those surveyed) believes

that their team may be cursed. Does this mean that they really believe in

Satanic forces that stymied Bill Buckner in 1986? Or that God or gods are

actually cursing their team for some sin committed in the past, such as

disallowing a man to enter the 1947 World Series with a billy goat? When something

so strange or unnatural goes on with a team, perhaps we need religious language

to describe it. Two, 21% of all fans “perform pre-game rituals or game-time

rituals.”

Does everyone (or even a majority) in this group actually believe

that some supernatural force is taking account of what they are wearing, making

sure that it corresponds to the orthodox ritual, and then rewarding the fan’s

team accordingly? Did Michael Jordan believe that God would prevent the

basketball from going in the basket if he forgot to wear his North Carolina

uniform underneath his Chicago Bulls one? Of course not! Superstitious behavior

in sports is probably closer to the act of hedging a bet—a bet that is made

tongue-in-cheek; not Pascal’s Wager. To classify ritualistic or superstitious

behavior as believing in the intervention of supernatural forces is misleading

at best.

However, the survey shows that religion

and sports come together for many fans; just not in the ways that one might

think. A better way to think of this relationship is that ritual and belief are

concepts used by both religion and sports in order to aid in the understanding

of the workings of the world—making reference to same reality. Our book, Religion and Sports in American Culture (Routledge 2014), attempts to find

cross-fertilization between religion and sports around a variety of

traditionally religious concepts. Yet in order to avoid the sentiment that the

sacred and secular cannot be so intimate with each other, we examine the

relationship between them from an atypical, culturally-informed angle.

However, the survey shows that religion

and sports come together for many fans; just not in the ways that one might

think. A better way to think of this relationship is that ritual and belief are

concepts used by both religion and sports in order to aid in the understanding

of the workings of the world—making reference to same reality. Our book, Religion and Sports in American Culture (Routledge 2014), attempts to find

cross-fertilization between religion and sports around a variety of

traditionally religious concepts. Yet in order to avoid the sentiment that the

sacred and secular cannot be so intimate with each other, we examine the

relationship between them from an atypical, culturally-informed angle.

From

what we have mentioned in the popular media and the recorded surveys that

inundate us about how religious Americans remain, despite a profound process of

secularization that dates back to the Enlightenment, we have concluded that

“postsecularism” is probably the right conceptual description of contemporary

American culture and the behavior displayed on television screens and in the

privacy of our homes.

Postsecularism is a variant of postmodernism and thereby

captures the spirit of how secular and religious practices coexist. If at one

point it was believed that the secularization of American culture—including the

designation of sports as the American Religion—would overshadow if not overtake

any traces of religious belief and practice, it has become evident that this

process did not and perhaps cannot fully undermine the strength and popularity

of religion. Like postmodernism that acknowledges the hold that modernism still

has on the conceptual organization of our world—from an appeal to a cognitive

foundation and the criteria by which we judge everything—postsecularism

appreciates the “both and” logical connection between the secular and the

religious, between the divine and the mundane. Popular culture and its

expressions in popular media remind us of this (bewildering) reality.

And, of course, when sports and religion

meet on the television screen or the pages of the Internet, it shouldn’t be

surprising (with postsecularism in mind) that they inform each other—with

historical antecedents and verbal cues—rather that claim exclusive authority to

render judgment on God’s presence in the Super Bowl or the teams that are

blessed or cursed. In short, postsecularism has performed an invaluable

intellectual function in undermining a perceived (and real at times when

biology textbooks are contested in some school districts) struggle and

antagonism between the religious and the secular in contemporary culture.

In our book we attempt to systematically

survey seven sets of comparison between the religious (admittedly limited to

the Judeo-Christian Bible) and the sports-world responses to concepts such as

belief, sacrifice, work, relics, pilgrimages, competition, and redemption. In

each case, we provide the textual and theological underpinning of these

concepts, their centrality for the Judeo-Christian tradition (with obvious points of difference between the

two religious traditions), their significance in various athletic activities

and the ethos that underlies them, and the contemporary interpretations that

were undertaken by the likes of Augustine and Calvin on one end of the

spectrum, all the way to Karl Marx and Max Weber on the other.

What becomes clear

from our perspective is the fact that previous approaches to the relationship

between religion and sports—the historical, sociological, economic, and psychological/personal—fall

short of the profound appreciation that these two cultural phenomena aren’t

reducible to each other. Without a reductionist methodology at work, the idea

that the one (religion) is (logically or chronologically) prior to the other (sports)

makes little sense; likewise, the idea that one of these cultural institutions

(structurally or linguistically) depends on the other is too simplistic.

Instead, we offer a more nuanced and rich intermingling of these phenomena within

the context of contemporary capitalist culture. Once understood culturally and

in terms of the reality of postsecularism, certain apparent confusions or

puzzling survey results can be more fruitfully understood.

We can go to church

on Sunday early enough to be able to go to the stadium later; we can feel the

camaraderie of fellow congregants just as strongly as our fellow fans (and

vice-versa). We can love our team and its quarterback this Super Bowl without

having blasphemed Jesus. If anything, the one practice and set of rituals

informs the other, and we import from one context to the other almost

seamlessly. There is always room at the inn and all are welcome under our

expanded (revival and sports) tent.

Comments