Social Gospel(s) in the American West? Five Possible Themes

Paul Putz

If I'm going to write about one notoriously nebulous historical concept anyway, why not double down?

For most people interested in American history, the term "social gospel" probably denotes an informal American religious movement that began sometime around the publication of Washington Gladden's Working People and Their Employers (1876) and faded in importance sometime after Walter Rauschenbusch's A Theology for the Social Gospel (1917). It involved a decreased focus on individual other-worldly salvation and an increased emphasis on applying Christ's teachings (especially in regards to fairness and justice) to fix temporal inequalities produced by the new industrial economic and political order.

That basic definition seems to remain the standard introductory description, although a number of questions have (let me apologize in advance for using this word) problematized social gospel historiography since the 1940s. To list just a few issues, historians still debate how radical social gospelers really were, how much continuity existed between social gospel reform and antebellum social reform, and what sort of theology imbued the movement (was it liberal? evangelical? a theology of its own? all of the above?). Then there's the problem of the word "social gospel" itself. Before the 1900s, what we now call the social gospel was often described with terms like practical Christianity, applied Christianity, or social Christianity.

As historians have debated and discussed who gets to be included as a social gospeler, they have created an impressive collection of strange bedfellows. While some social gospel boundaries are firm -- for example, the social reform efforts of the Salvation Army, the Church of the Nazarene, and other holiness movement groups are excluded -- the tendency among historians has been to broaden the scope of the social gospel. If only I had the power, I would invite all the individuals who have been labeled as social gospelers to a dinner party just to listen to their awkward conversations and see their shocked faces when I informed them that they were all part of the same reform movement (Thomas Dixon? Please meet Reverdy Ransom).

I don't want to be too dismissive, though. Like Janine Giordano Drake, I believe that the social gospel is an important subject to take on. Clearly, there was something going on in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century as more and more Americans sought to address the "social question" and to reshape institutions and the nation in the image of their notion of the kingdom of God. In my mind, more work needs to be done on the social gospel(s), not less.

As for the American West, definitional issues abound. Is it a process or a place? If it's a place, where? How should we differentiate between the many Wests? If we can't even figure out what the American West is, how can we take a western regional approach to religion? Quincy Newell covered both the difficulties and potential of religion in the American West in this fantastic (but not open-access) overview. The task before scholars of religion in the American West is indeed great, but so are the possibilities.

I read Newell's article earlier this year as I was plowing through social gospel historiography from C. Howard Hopkins to Heath Carter, and I began to wonder what a western view of the rise of the social gospel might look like. Some historians of the American West, like Doug Anderson, have analyzed western expressions of the social gospel and numerous others have written about individual western social gospelers such as Kansas's Charles Sheldon and Iowa's George Herron. Usually, though, Sheldon and Herron are written about it an "oh, and they happened to be from the Midddle West" way. As it is with most aspects of American religious history, scholars rarely incorporate a robust western perspective on the social gospel. Questions go unasked. How did the specific context of American West communities shape social gospel expressions? What impact, if any, did western forms of the social gospel have on those in other parts of the country? Was there even a distinct western social gospel?

In regards to the last question, Ferenc Morton Szacz answered with an emphatic "yes." In both The Protestant Clergy in the Great Plains and Mountain West, 1865-1915 (1988, reprinted in 2004) and Religion in the Modern American West (2002), Szacz laid out the characteristics of a western social gospel. In Protestant Clergy, he listed three specific western distinctives: "the establishment of Chinese schools; aid for immigrant health seekers in the Southwest; and the popular ideology of social ethics created by Topeka Congregationalist Charles M. Sheldon." In Religion in the Modern American West he expanded on his earlier examples, but also took to using the term "Gospel-In-The-World" interchangeably with social gospel.

I appreciated Szacz's attempts to identify a western social gospel, but his analysis was somewhat problematic. For example, Szacz did not explain how Sheldon’s urban Great Plains context might have inspired a distinct western form of popular social ethics. Were Sheldon’s popular social gospel novels really all that different from those further east? If so, how did the West shape those differences? As for health seekers, the mountain West undoubtedly attracted visitors for health purposes. But it is unclear how improving individual health might be connected to a social gospel that sought to Christianize institutions. Too often, Szacz seemed to equate any charitable work with the social gospel.

On the other hand, Szacz pointed to three promising social gospel themes for the West. I'll briefly discuss those three, and then add two more possibilities.

1) Szacz suggested that in the chaotic world of pre-social gospel western cities, clerics became de facto civic leaders. When the social gospel came along in the late 1800s it simply reinforced western ministers' already-existing role of meeting the temporal needs of their community. Of course, this notion of continuity assumes that the social gospel was driven by the clergy. Heath Carter paints a different story of the social gospel, as do some historians of the Populist movement (see below). Even so, social gospel efforts in the suddenly booming postbellum western cities, which lacked the infrastructure and established order of their eastern counterparts, might be worth analyzing.

2) Although Szacz did not exactly use the phrase "multiculturalism," his mention of Chinese schools hinted at the theme. Johsua Paddison has recently shown how valuable analyzing the mix of race and religion in late-nineteenth century California can be to our understanding of reconstruction. The West provides an especially conducive setting to move beyond the black/white racial binary, and scholars looking at the social gospel in the West would find much to emulate in Paddison's approach. William Deverell and Mark Wild, authors of an essay in Race, Religion, Region: Landscapes of Encounter in the American West (2006), utilized the multicultural theme in their discussion of social gospeler Garfield Bromley Oxnam and his failed efforts in the 1920s to lead the multiracial Church of All Nations in Los Angeles. Deverell and Wild viewed Oxnam's church as "another iteration of the classic western desire for a more perfect community, albeit one that claimed to reject the racist baggage characteristic of so many other efforts.”

Ralph Luker and Ronald C. White Jr. brought race to the forefront of social gospel history in the early 1990s. To move beyond their "social gospel in black and white," scholars should look West.

3) Szacz argued that western cities were especially favorable to ecumenical social work. In Denver in the 1890s, for example, a group of Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish leaders, united in their interest in advancing the kingdom of God, agreed to exchange pulpits. Myron Reed, a Congregationalist minister in the city, summed up the ecumenical spirit he tried to foster in Denver, recalling “I saw a Jewish rabbi, a Catholic priest, an Episcopalian rector and a Congregational parson in one carriage going to the burial of a newspaperman who belonged to no church.” Of course, social gospel efforts in the East were also marked in some cases by a similar ecumenical spirit, so any analysis of western social gospel ecumenicism would need to compare western and eastern urban settings.

4) Beyond the potential social gospel distinctives mentioned by Szacz, at least two more possibilities should be considered. First, the West was more conducive to women's suffrage than any other region in the U.S. Perhaps the increased political freedom afforded to women in the West shaped the forms that the social gospel took, or led to increased female leadership in social gospel activity. Although women were heavily involved in church-related societies and organizations, they also played a prominent role in groups not affiliated with a specific denomination. For example, the national Women's Club Movement that emerged in the late nineteenth century became an important part of most urban settings in the West, and it allowed women to consolidate their forces in local settings in the interests of Christianizing the local social order.

5) The prominence of the Populist movement (and its precursors) in the West cannot be ignored. The Populist movement was powerful in both the South and West, so it was not solely a western phenomenon. Even so, the agrarian or rural "social gospel from below" deserves notice from social gospel historians as a corrective to the eastern-focused urban social gospel narrative. Historians Richard C. Goode and Charles Postel, among others, have noticed the way that many Populist leaders utilized notions of the kingdom of God and the brotherhood of man to advance their reform agendas. However, since the organizations associated with Populism were not religious institutions, they tend to get overlooked in favor of the church-based view of the social gospel. This despite the fact that a former Populist helped to popularize the term "social gospel" in the first place. Nebraskan George Howard Gibson, a Prohibitionist-turned-Populist-turned-Socialist, formed a socialist colony in Georgia in the late 1890s. The colony's official publication was titled the Social Gospel, and the commune received publicity from leading Christian socialists as well as from newspapers across the country. (Side note: Check out Chapter 8 in Charles Postel's The Populist Vision for a more thorough comparison between the faith of social gospelers and that of the Populists.)

The five possible themes for western social gospels mentioned above are only cursory. Feel free to pass along any comments or suggestions, especially if you have any examples of scholars who have articulated a distinct western regional social gospel perspective (i.e., not just an individual biography of a social gospel westerner). I'd also be interested to know of any scholars who, in the process of discussing the broad social gospel, have made it a point to incorporate a western perspective.

In the meantime, be on the lookout for upcoming work related to the social gospel from Heath Carter, Janine Giordano Drake, Curtis Evans, and others. If you need a refresher course or an introduction to the issues related to the social gospel, this article from Elna Green at the (open-access!) Journal of Southern Religion includes an overview of the state of the field as well as a good collection of footnotes for further reference.

If I'm going to write about one notoriously nebulous historical concept anyway, why not double down?

|

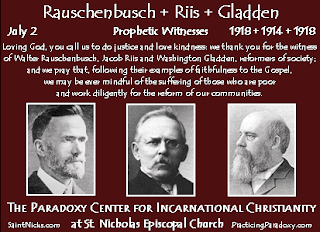

| An Episcopalian feast day commemorates the leading social gosepelers. Accessed via holywomenholymen.wordpress.com |

That basic definition seems to remain the standard introductory description, although a number of questions have (let me apologize in advance for using this word) problematized social gospel historiography since the 1940s. To list just a few issues, historians still debate how radical social gospelers really were, how much continuity existed between social gospel reform and antebellum social reform, and what sort of theology imbued the movement (was it liberal? evangelical? a theology of its own? all of the above?). Then there's the problem of the word "social gospel" itself. Before the 1900s, what we now call the social gospel was often described with terms like practical Christianity, applied Christianity, or social Christianity.

As historians have debated and discussed who gets to be included as a social gospeler, they have created an impressive collection of strange bedfellows. While some social gospel boundaries are firm -- for example, the social reform efforts of the Salvation Army, the Church of the Nazarene, and other holiness movement groups are excluded -- the tendency among historians has been to broaden the scope of the social gospel. If only I had the power, I would invite all the individuals who have been labeled as social gospelers to a dinner party just to listen to their awkward conversations and see their shocked faces when I informed them that they were all part of the same reform movement (Thomas Dixon? Please meet Reverdy Ransom).

I don't want to be too dismissive, though. Like Janine Giordano Drake, I believe that the social gospel is an important subject to take on. Clearly, there was something going on in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century as more and more Americans sought to address the "social question" and to reshape institutions and the nation in the image of their notion of the kingdom of God. In my mind, more work needs to be done on the social gospel(s), not less.

As for the American West, definitional issues abound. Is it a process or a place? If it's a place, where? How should we differentiate between the many Wests? If we can't even figure out what the American West is, how can we take a western regional approach to religion? Quincy Newell covered both the difficulties and potential of religion in the American West in this fantastic (but not open-access) overview. The task before scholars of religion in the American West is indeed great, but so are the possibilities.

I read Newell's article earlier this year as I was plowing through social gospel historiography from C. Howard Hopkins to Heath Carter, and I began to wonder what a western view of the rise of the social gospel might look like. Some historians of the American West, like Doug Anderson, have analyzed western expressions of the social gospel and numerous others have written about individual western social gospelers such as Kansas's Charles Sheldon and Iowa's George Herron. Usually, though, Sheldon and Herron are written about it an "oh, and they happened to be from the Midddle West" way. As it is with most aspects of American religious history, scholars rarely incorporate a robust western perspective on the social gospel. Questions go unasked. How did the specific context of American West communities shape social gospel expressions? What impact, if any, did western forms of the social gospel have on those in other parts of the country? Was there even a distinct western social gospel?

In regards to the last question, Ferenc Morton Szacz answered with an emphatic "yes." In both The Protestant Clergy in the Great Plains and Mountain West, 1865-1915 (1988, reprinted in 2004) and Religion in the Modern American West (2002), Szacz laid out the characteristics of a western social gospel. In Protestant Clergy, he listed three specific western distinctives: "the establishment of Chinese schools; aid for immigrant health seekers in the Southwest; and the popular ideology of social ethics created by Topeka Congregationalist Charles M. Sheldon." In Religion in the Modern American West he expanded on his earlier examples, but also took to using the term "Gospel-In-The-World" interchangeably with social gospel.

I appreciated Szacz's attempts to identify a western social gospel, but his analysis was somewhat problematic. For example, Szacz did not explain how Sheldon’s urban Great Plains context might have inspired a distinct western form of popular social ethics. Were Sheldon’s popular social gospel novels really all that different from those further east? If so, how did the West shape those differences? As for health seekers, the mountain West undoubtedly attracted visitors for health purposes. But it is unclear how improving individual health might be connected to a social gospel that sought to Christianize institutions. Too often, Szacz seemed to equate any charitable work with the social gospel.

On the other hand, Szacz pointed to three promising social gospel themes for the West. I'll briefly discuss those three, and then add two more possibilities.

|

| 1881 Map of Denver. Accessed via USGWarchives. |

2) Although Szacz did not exactly use the phrase "multiculturalism," his mention of Chinese schools hinted at the theme. Johsua Paddison has recently shown how valuable analyzing the mix of race and religion in late-nineteenth century California can be to our understanding of reconstruction. The West provides an especially conducive setting to move beyond the black/white racial binary, and scholars looking at the social gospel in the West would find much to emulate in Paddison's approach. William Deverell and Mark Wild, authors of an essay in Race, Religion, Region: Landscapes of Encounter in the American West (2006), utilized the multicultural theme in their discussion of social gospeler Garfield Bromley Oxnam and his failed efforts in the 1920s to lead the multiracial Church of All Nations in Los Angeles. Deverell and Wild viewed Oxnam's church as "another iteration of the classic western desire for a more perfect community, albeit one that claimed to reject the racist baggage characteristic of so many other efforts.”

Ralph Luker and Ronald C. White Jr. brought race to the forefront of social gospel history in the early 1990s. To move beyond their "social gospel in black and white," scholars should look West.

3) Szacz argued that western cities were especially favorable to ecumenical social work. In Denver in the 1890s, for example, a group of Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish leaders, united in their interest in advancing the kingdom of God, agreed to exchange pulpits. Myron Reed, a Congregationalist minister in the city, summed up the ecumenical spirit he tried to foster in Denver, recalling “I saw a Jewish rabbi, a Catholic priest, an Episcopalian rector and a Congregational parson in one carriage going to the burial of a newspaperman who belonged to no church.” Of course, social gospel efforts in the East were also marked in some cases by a similar ecumenical spirit, so any analysis of western social gospel ecumenicism would need to compare western and eastern urban settings.

|

| 1915 cartoon by Hy Mayer in Puck, accessed via Library of Congress |

The five possible themes for western social gospels mentioned above are only cursory. Feel free to pass along any comments or suggestions, especially if you have any examples of scholars who have articulated a distinct western regional social gospel perspective (i.e., not just an individual biography of a social gospel westerner). I'd also be interested to know of any scholars who, in the process of discussing the broad social gospel, have made it a point to incorporate a western perspective.

In the meantime, be on the lookout for upcoming work related to the social gospel from Heath Carter, Janine Giordano Drake, Curtis Evans, and others. If you need a refresher course or an introduction to the issues related to the social gospel, this article from Elna Green at the (open-access!) Journal of Southern Religion includes an overview of the state of the field as well as a good collection of footnotes for further reference.

Comments