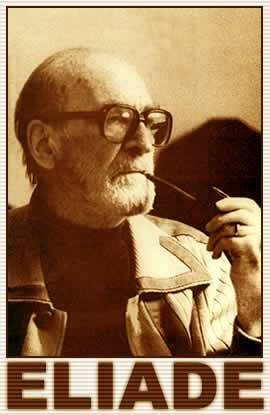

The History of Religion in American Religious History; Or, the Eliadian Roots of Liberal Religion

By Michael J. Altman

Perhaps, Eliade was right. Perhaps there really is an eternal return. And, perhaps, it is time for his.

I'm teaching Mircea Eliade's approach to the "History of Religions" this week in my introduction to Religious Studies course. We've covered Durkheim, Freud, Hume and even Tylor. We've found functionalist explanations of religion in European thinkers.

Then comes Eliade. In America.

Eliade refuses to explain religion. Rejecting the reductionism of psychoanalysis or sociology, Eliade demands that religion be understood "on its own terms." We do not explain religion, rather, the historian of religion describes and categorizes religion. The historian of religions looks for symbols, myths, and archetypes through comparison. Because the sacred is sui generis, unique, irreducible, we should seek understanding, interpretation, and pattern. Explanation is anathema.

It was this approach--comparative, descriptive, phenomoneological--that dominated the field of religious studies in the latter third of the twentieth century in America. It was this approach that as a student I was warned away from and handed a J. Z. Smith article.

And it was this approach that had a profound effect on the way Americans would imagine something called "comparative religion" and the ways Americans imagined the sacred and spirituality. As Daniel Pals wrote (and I read for our class this week):

His position at Chicago, where he remained for the rest of his young life, enabled him to serve as mentor to a full generation of talented younger scholars who were inspired by his example, even when, as was common, they proceeded to disagree with his views...When he came to Chicago, there were three significant professorships in the history of religions in the United States; twenty years later, there were thirty, half of which were occupied by his students. (p. 196)In the wake of the Schempp case, Eliade's students, books, and ideas would structure new courses in "comparative religion" around the country. The religious studies of the 60s, 70s, and 80s, would follow Eliade's descriptive, phenomenological, and interpretive lead. His refusal to explain away the sacred and his project of tracing its various eruptions in archaic cultures dovetailed nicely with a liberal (post?)Protestant approach to religion as meaning-making system.

The recent, and very welcome, interest in liberal twentieth century religion has yet to account for Eliade and any effect he may have had on American liberal understandings of religion.Other scholars of comparative religion, such as Huston Smith, have figured into some narratives of liberal religion in America. I pulled every American religious history survey or liberal religion book off my shelf and found nary a mention of Eliade. In Religious Studies circles, pond-fulls of ink have been spilled to drown Eliade's theories and methods. But in American religious history, questions about Eliade remain.

How many Americans took "comparative religion" courses in the three decades of Eliade's popularity in the field? How many people read The Sacred and the Profane? How many saw Hugh Grant play a fictionalized autobiographical Eliade?

My hypothesis is this: Eliade provided an intellectual bridge between liberal Protestant understandings of comparative religion such as James Freeman Clarke's Ten Great Religions, and the experimental hot house of 1960s and 1970s college campuses. In the wake of the Schempp decision, with the doors flung wide open for some sort of secular study of religion, in walked a Romanian philosopher and intellectual who could simultaneously represent European seriousness while rejecting the European tradition of functionalist theories of religion, and give many American students what they wanted--a comparative religion that told them the sacred was real, that it could be found outside the dogmatism of their parents, and that it could transform them.

Eliade described the terror of history and the myth of the eternal return. Now it is time for his own return within history--within American religious history.

Comments

Which is also why I'd like to see far more statistical rigor in RS and admire

http://usreligion.blogspot.com/2013/10/historical-religion-data-in-nhgis-and.html

good faith attempts at it.

Not that their story isn't marginally interesting in its own right, but we need to know just how many Zoroastrian transsexuals in 1840s Wisconsin we're talking about, just to have a feel for the spirit of the times.

Phillip, to follow what Chip said, I totally agree that ARH and RS are different. And I also agree that the Immigration Act had a lot to do with the growth of religious studies.

But, I still think the story of how religious studies grew on campuses in the 60s and 70s and the effect that comparative religion courses had on Americans who took them in college and then went on to jobs outside the academy is ripe for American religious history. In effect, religious studies itself should be data for American religious history. For example, a colleague who read this post showed me the first few pages of Robert Ellwood's book on Eliade and myth where Ellwood recounts how Eliade's writing helped him make sense of his time overseas in Asia during WWII and his encounter with religious difference. Before he ever set foot in graduate school, Ellwood's own religious views were deeply shaped by Eliade's work. One wonders if others had a similar experience. Perhaps the Immigration Act and Schempp together made Eliade's success possible. Comparative religion was now possible in the college classroom and necessary for explaining the new post-immigration America.

A few people on Twitter mentioned that I forgot William James in my account. Indeed, I did. But I think James can be understood as another liberal Protestant bridge between the older models and the history of religions that Eliade brought. Though I need to give James' place in this story a bit more thought.