The Deep and Wide Worlds of Billy Graham

A hearty welcome to our new contributor Michael Hammond, Professor of History at Southeastern University, and an attendee at the recent Billy Graham Conference which we blogged about here before. Raised in Indiana, Michael did his MA with Mark Noll at Wheaton, and took his Ph.D. at the University of Arkansas. At Southeastern, he enjoys teaching Baseball and America, the Civil Rights Movement, and American Christianity and Culture Since 1945. His research is on the intersection of race and religion, especially with regards to political movements.

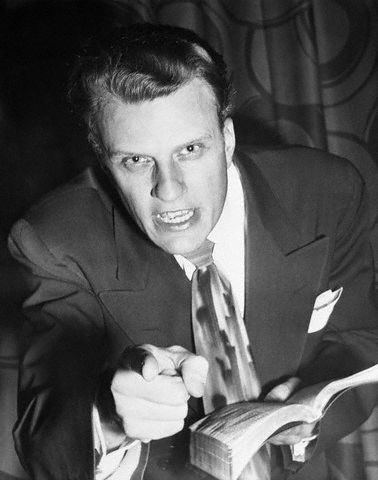

Despite their areas of staunch disagreement, scholars of 20th century American evangelicalism have had little trouble agreeing on the identity of the movement’s key standout figure. Few religious leaders, past or present, have rivaled the influence of Billy Graham. Graham's legacy has not only shaped Christianity but post-World War II America. It should not be surprising, then, that the Billy Graham Center and Archives have become a center for global study of American Christianity.

The “Worlds of Billy Graham” conference provided an

opportunity to join other scholars in my field to explore Graham’s

legacy. Meeting in the Cliff Barrows Auditorium at the Billy Graham

Center at Wheaton College, the purpose of this gathering was not to debate

whether Graham mattered, but rather to measure the length of his shadow. Presenters

at the conference brought original research in support of chapters for a book

project funded by the Lilly Endowment grant. This forthcoming book will focus

on the worlds of Billy Graham—assessing his cultural and political influence.

Presentations evaluated Graham’s influence on these important “macroscopic” worlds,

and the symbolic influence Graham had around the globe. But in doing so, these

papers also revealed the ways that Graham shaped the “microscopic” level of

personal Christian practice.

Project co-director Grant Wacker framed this series

of presentations around a critical question “how did Billy Graham shape what it

means to be modern, Christian, and American?” In introducing the question,

Wacker offered a humorous but sobering vignette. During a recent visit to

a respectable New England college, only one member of the student audience was

able to identify the name Billy Graham. Unfortunately for Wacker, this

same student was remembering “Superstar Billy Graham,” the professional

wrestler from the 1970s. The implication of Wacker’s story was clear.

Since Graham conducted his last crusade meetings in New York City in 2005, his

visibility has faded. The assembled historians in Wheaton are penning the

stories that will pass on Graham’s legacy to a generation that has no living

memory of stadium crusades, the music of George Beverly Shea, or seeing the

prayerful Graham appear beside presidents from both parties.

Graham’s

crusade meetings were the foundation of his ministry work, and Michael Hamilton

focused on the lack of ritual in his simple evangelical message. Still, there

were formulaic elements of these meetings, including celebrity appearances and

musical performances to prime the audience toward the crescendo of Billy’s appeal.

As Edith Blumhofer explained, singing and music were especially influential

parts of these crusades, and were consistently led by Cliff Barrows and George

Beverly Shea in support of Graham. The partnership of these three men, dating

back to the late 1940s, was brought together when Shea, already a popular radio

singer, was the best-known among the three men. Their formula of music and a

common sense appeal to religious revival expanded with the advent of televised

crusade meetings and performances by popular musicians. Graham demonstrated the

appropriation of popular music in his meetings, and would feature many

contemporary musicians, most famously Ethel Waters and Johnny Cash. These warm

up acts often featured Christian rock bands that brought in a younger crowd to

the meetings. Elesha Coffman explained that as Graham’s use of the media

expanded his audience, he had to answer the cynics who saw in him the

hucksterism of other preachers who were utilizing the television airwaves.

Rather than name the most egregious offenders among his fellow evangelists,

Graham distanced himself from the fictional character of Elmer Gantry. Despite

Hamilton’s salient point about the lack of ritual in Graham crusades, he

fashioned a modern liturgy for evangelicals. The setting of football stadiums

demonstrated the magnitude of Graham’s ambitious ministry goals, and played

well on television as sweeping panoramas showed a crowd on par with a

championship game. In the midst of these massive crowds, the audience at

home—and in the cheap seats—could see the appeal of Graham on large screen

television shots. Today, many churches, mega and otherwise, use video screens

and closed circuit video cameras to project the message in larger than life

size for the audience. Preachers learn to appeal to the camera as much as they

seek to eyeball the audience. The fascination with sanctified celebrities was

not a sole creation of Billy Graham, but he demonstrated the appeal for viewers

and the power of testimony in the media age.

Billy

and his wife Ruth Bell Graham projected ideal models for evangelical manhood

and womanhood. As Anne Blue Wills showed, Ruth demonstrated an ideal model of

the “pretty” pastor’s wife through the media. Wills portrayed Ruth as an active

writer and thinker who contributed her own family-oriented stories and poetry,

as well as adding to Billy’s books, including Peace With God. Seth Dowland focused on Billy Graham’s manhood,

embodied in his “desirable but off limits” good looks and patriotic certitude.

The famous Modesto Manifesto kept Graham and his associates from any hint of

sexual impropriety by establishing covenantal rules for interaction with

members of the opposite sex. These safe complementation role models were an

asset to the Graham ministry, but also reinforced the resistance to the modern

feminist movement. This brought to mind how ubiquitous ministries for men and

women are in and around church life today. Promise Keepers, Women of Faith, and

local churches perpetuate these covenants and accountability meetings for modern

evangelicals.

For

many, the first “world” of Billy Graham they ever saw was on screen. Often,

this was in one of the films produced by Worldwide Pictures, featuring (spoiler

alert!) a climactic scene of Graham’s preaching. Those in attendance were treated

to a showing of the 1953 film Oiltown U.S.A.,

which demonstrated the immediacy of the salvation message with lines such as “a

well is just a hole in the ground until it comes in.” Like the gushing wells on

the Texas plain, life could change in an instant. The oil industry was a

fitting backdrop for Graham’s movie given his relationships with oil executives

such as Sid Richardson and J. Howard Pew, as well as Texas dairy magnate Morris

Calvin Oldham, who paid production costs for Oiltown U.S.A. This Texas-focused analysis was the basis for Darren

Dochuk’s call to reinterpret Graham’s stance on race and social issues. Did

Texas capitalists influence Graham on these issues more than his own roots in

the Solid South? Graham was interpreted by many as going along rather than

leading the parade for social change. This may be due to his alliance with

Texans eager to move the center political coalition out of the Democratic Party

and toward the GOP. Links between Graham and these businessmen brought to mind

the corporate evangelicalism embodied in success-oriented leadership gurus and

conferences. While business interests been at the center of American religion

since the colonial period, the alliance of corporate America and Christianity

has grown more intertwined in recent years.

It

was during the 1950s that many Americans began to view Graham as the unofficial

White House chaplain, a perception that only grew through the Lyndon Johnson

and Richard Nixon administrations. This gave Graham a platform for the evangelical

social ethic that Carl Henry and Harold Ockenga, among others, had promoted as

a foundational Christian virtue. For example, David King pointed toward

Graham’s filmed tour with Sargent Shriver in support of Lyndon Johnson’s War on

Poverty. Curtis Evans showed that Graham followed the lead of Henry in doubting

the possibility of social change without personal salvation. On civil rights,

Steven Miller explained that Graham was portrayed in Marshall Frady’s writing

as an outdated Southern archetype, more “Mayberry than Charlotte.” In these

examples, Graham’s best avenue for social change was his access to the White

House. This focus on winning the highest office in the land remains a dominant

political focus for evangelical activists.

As

the best-known religious celebrity in America, Graham was often asked for his thoughts

on issues of the day. Andrew Finstuen pointed out that Graham’s simple approach

to public life was criticized by Richard Hofstadter, yet Graham contemplated

launching two colleges: Crusade University in 1959, and Billy Graham University

in 1967. While neither of these schools ever opened, the connection between

public Christianity and higher education was realized with the growth of evangelical

colleges. In the late 20th century, hundreds of these schools progressed from church-affiliated

ministry training centers to liberal arts colleges focused on saturating

professional fields with their graduates.

These

scholars portrayed Graham as a humble and committed evangelist and American celebrity

over the duration of his public life. The final session featured Wacker and

Blumhofer facilitating a conversation with Martin Marty, former Newsweek religion reporter Ken Woodward,

Graham’s sister Jeanne Graham Ford and her husband, BGEA Associate Leighton

Ford. Martin Marty suggested that Graham belonged alongside Martin Luther King,

Jr. and Jonathan Edwards on the Mount Rushmore of American Protestant influence.

Graham also stayed true to his vocational calling to evangelism, in Marty’s

estimation, and quickly rushed back when his political or theological opinions

diminished his voice. The best-known evangelical of the modern era was a

professional evangelist who appropriated television, radio, film, print media, marketing

techniques, rock & roll, politics, and other modern methods of

communicating his message, yet avoided the criticism that other technological

preachers warranted. Modern evangelical churches emulate Graham’s crusade

formula without knowingly imitating his approach.

During

the closing session, Wacker posed the last question for the panel as simply

“what’s next?” What follows Billy Graham? George Marsden once wrote that there

was a time when the simplest way to identify an evangelical was “anyone who

likes Billy Graham.” In looking outward and inward at American Christianity,

Graham’s influence is easy to overstate because it is very difficult to

separate the movement of evangelicalism from its best-known symbol, Billy

Graham. And yet, that is the point. With Graham approaching his 95th

birthday, scholars continue to assess his impact on American life and the

continuing development of evangelicalism in the wake of his public ministry. Graham’s

influence was not only the various worlds that he shaped on the large scale,

but also in the everyday, ongoing practice of Christianity by normal, earnest

people who faithfully paraded to their local church on Sundays. Perhaps

Graham’s even greater influence was how his example of personal fidelity to his

calling as an evangelist modeled restraint in the shaping of American religion.

It is daunting to consider what evangelicalism may look like in the future

without his example.

Comments