Rethinking the Garrisonians

Carol Faulkner

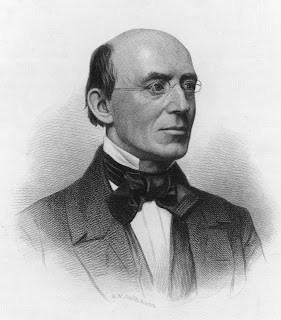

Carol FaulknerCaleb McDaniel's new book, The Problem of Democracy in the Age of Slavery: Garrisonian Abolitionists & Transatlantic Reform, makes the counter-intuitive argument that William Lloyd Garrison and his allies, known for their rejection of American politics, were in fact political thinkers. One of my favorite, amusing quotes about the Garrisonians comes from James Gordon Bennett (who else?), who described Garrison's American Anti-Slavery Society as home to "Non-resistants, Infidels, Socialists, Atheists, Grahamites, Pantheists, and all the disaffected materials afloat on the bosom of society." According to McDaniel, historians have created a similar portrait of Garrison: "the classic image of Garrison is of an impractical, 'radically antinomian' religous reformer obsessed with moral perfectionism" (9). Instead, McDaniel makes a convincing argument that Garrisonian abolitionists were committed to democracy and republican government. Rather than vote, they sought to influence politics through public opinion. Garrisonians also confronted the difficulties of democracy--majority rule, particularly public opinion that was openly hostile to abolition--but they did not abandon their faith that agitation could bring about change.

Even for those immersed in the primary and secondary sources on radical abolition, McDaniel's book will encourage readers to rethink the Garrisonians. Take his analysis of the familiar, and oft-criticized, strategy of "moral suasion":

Garrison retained his belief that American institutions were at least freer and more open to change than the kingly and aristocratic governments that plagued the "Old World." Indeed, that was why Garrison relied exclusively on the tools of "public opinion" as he began his crusade. From the start, Garrison regularly announced that "the great work of national redemption" could be accomplished "through the agency of moral power--of public opinion--of individual duty," a three-pronged set of means that historians have sometimes too quickly reduced to the single phrase "moral suasion." (41)

Though McDaniel's focus is on the Garrisonians' complex relationship to American democracy and their link to democratic reformers in Europe, he also analyzes the relationship between abolitionists' political and religious thought. He writes that Garrison's allies in the British isles tended to be "Quakers and Unitarians who were tolerant of unorthodox religious views" (76). In a chapter on non-resistance (Chapter 5, "The Problem of Nationalism"), he examines the influence of John Humphrey Noyes' perfectionism on Garrison. Noyes convinced Garrison to leave the church, as well as abstain from voting, but he did not convince Garrison to abandon his allegiance to the transatlantic anti-slavery movement and its own messy politics. Further, Garrisonians prided themselves on their cosmopolitanism, and they viewed patriotism/nationalism as a selfish weakness. As McDaniel writes, abolitionists saw "coming out" as a "'going in' to new relationships and communities not governed by geography or nationality" (120). In other words, the abolitionists' brand of perfectionism believed in a government of God that transcended country. While they may have believed that American institutions were flawed, however, Garrisonians preferred them to monarchy.

The Civil War temporarily alienated this transatlantic community of abolitionists. British abolitionists were shocked by Garrison's abandonment of disunion, accusing Garrison and other new Union supporters of succumbing to patriotism, foolish to attribute anti-slavery sympathies to the American government. American abolitionists viewed the opinions of British abolitionists as similarly blinded by nationalism and their government's problematic neutrality. McDaniel argues, "What these quarrels ultimately revealed was how much national feeling survived despite all the abolitionists' invocations of "Our Country is the World"" (228). As McDaniel shows, even with their harsh criticism of the American government, including Garrison's burning of the constitution, abolitionists expressed hope for its democratic institutions.

Comments