The Place of Catholic Women's Culture

Today's guest post comes from Monica L. Mercado, who is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of History at the University of Chicago. Her dissertation, "Women and the Word: Gender, Print, and Catholic Identity in Nineteenth-Century America," explores the emergence of a vibrant American Catholic publishing industry at mid-century and the women readers, writers, and institutions that grew up around it. In 2012-2013 Monica is a fellow-in-residence at Chicago’s Center for the Study of Gender and Sexuality, where she also coordinates a public history program. You can find more details about her research and teaching interests in women’s and gender history at monicalmercado.com.

By Monica L. Mercado

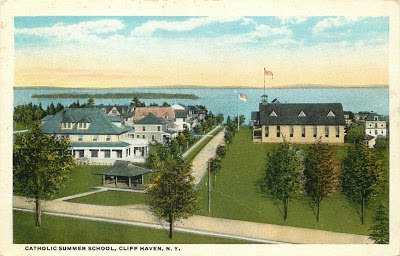

As we reach the end of the academic year, rushing toward deadlines, turning in final grades, and maybe even planning some summer travels, I can’t help but turn to one of my favorite forgotten sites of American religious history: the Catholic Summer School of America, located at Cliff Haven, New York, on the western shores of Lake Champlain. Founded in 1892 as an outgrowth of the Catholic Reading Circle movement, the Summer School has piqued my interest as a space that fostered important bonds between Catholic laywomen at the turn of the century.

As we reach the end of the academic year, rushing toward deadlines, turning in final grades, and maybe even planning some summer travels, I can’t help but turn to one of my favorite forgotten sites of American religious history: the Catholic Summer School of America, located at Cliff Haven, New York, on the western shores of Lake Champlain. Founded in 1892 as an outgrowth of the Catholic Reading Circle movement, the Summer School has piqued my interest as a space that fostered important bonds between Catholic laywomen at the turn of the century.Last month, Smithsonian Magazine asked, “Where was the Birthplace of the American Vacation?” The answer? New York’s Adirondack Mountain region, which by the late 1860s became increasingly accessible to East Coast elites. “By 1900,” Smithsonian tells us, “the Adirondacks’ summer population had risen to around 25,000 from 3,000 in 1869.” The natural beauty of the area attracted tourists as soon as boats and trains could easily reach it—among them, it turns out, thousands of Catholic visitors in search of an experience similar to the Methodist’s Chautauqua assemblies. In upstate New York, Catholics discovered a co-ed retreat centered on their intellectual and cultural aspirations.

Laity and religious orders organized Catholic Summer Schools on a smaller scale in Wisconsin, Maryland, and California, and a Catholic Winter School in New Orleans operated briefly during the late 1890s. But the best-attended, longest running effort was that at Cliff Haven. Local hotels advertised vacancies in Catholic magazines and newspapers, while parishes and lay groups built permanent cottages at the site. President McKinley visited twice, in 1897 and 1899. By 1900, after a summer that counted nearly three thousand visitors, the Catholic Summer School grounds boasted an auditorium for the daily lecture program, a dining room that seated eight hundred, a small chapel, a library, and guesthouses. Men and women participated in discussions on literary topics, theological questions, and current affairs (over the course of just one day visitors could listen to talks on “Capital Punishment,” “Popes of the 19th Century,” and “The Relation of Buddhism to Christianity”). Here, for eight weeks each summer, the lecture hall, cottage, and campfire, not the chapel, organized life for Catholics who could afford the time and money.

Word of the Summer School spread across Catholic and secular presses from Boston to Bismarck, with breathless newspaper accounts announcing the formation of a retreat that would “rival Chautauqua.” Many of those papers also reported on women’s active role in the Summer School’s programs. Unlike the church pulpit, the Summer School auditorium became a site where women speakers did not appear out of place. Using this platform, they argued that Christianity provided women with an opportunity to lead, to read, to speak out, and to be active in Catholic life. They exemplified the career possibilities for unmarried Catholic women, finding purpose and career outside the convent (many of the lay women guests at the Summer School - most notably, Boston editor Katherine E. Conway. In short, the Catholic Summer School of America quickly became known as a place where some of the nation’s most active laywomen could gather together, in an era before the widespread availability of a Catholic women’s college education and decades before the formation of other networks such as the National Council of Catholic Women.

Women at the Catholic Summer School of America created new links to one another with the organization of the “Alumnae Auxiliary Association” (AAA) in 1893. The AAA served as the first formal organization of Catholic convent schools graduates in the nation and its members met throughout the year to socialize and fundraise with the purpose of endowing a lectureship in English Literature at the Summer School (they met their goal in 1904). The wording of the AAA mission statement - “to keep the [summer] school in touch with progressive women” - further illustrates what I see as the retreat’s usefulness in providing space for women from around the region to meet or reestablish old ties, speak to mixed audiences, and celebrate their achievements and status.

The Catholic Summer School of America was by no means a feminist utopia—this was, after all, a site that combined learning and leisure travel with the gendered norms of Roman Catholicism and turn-of-the-century American culture. Little girls dressed in white bearing ribbons paraded around the grounds while their parents attended lectures. A boy’s camp provided leadership training and amusements for young men, but no group stepped up to provide equivalent activities for young women. The Summer School’s Recreation Committee separated men and women for many of the daily activities (including tennis, archery, golf, and cycling). Plus, the moment was short-lived: by 1920, the Summer School shifted its primary mission to providing space for University Extension courses, and the grounds closed permanently during World War II.

Still, I find the Summer School an intriguing site for following the paths taken by Catholic laywomen, “careerists” who earned their living by writing and teaching. Summer School materials, AAA reports, even Catholic women’s fiction of the era suggest that the Catholic Summer School of America filled a social need apart from the home or parish, marking the arrival of an American Catholicism interested in self-culture. These sources also suggest to me ways of re-locating the history of Catholic women. It reminds us that the study of religious women sometimes takes us to places beyond the parlor, pew, or schoolroom. And it begs the question: what are you doing on your summer vacation?

Comments

I hope to make it up to Plattsburgh this summer and dig through some local histories. I grew up in Albany, actually, so when I came across the Summer School during the course of my dissertation research, it was quite a surprise!