My Search for Creflo Dollar

Paul Harvey

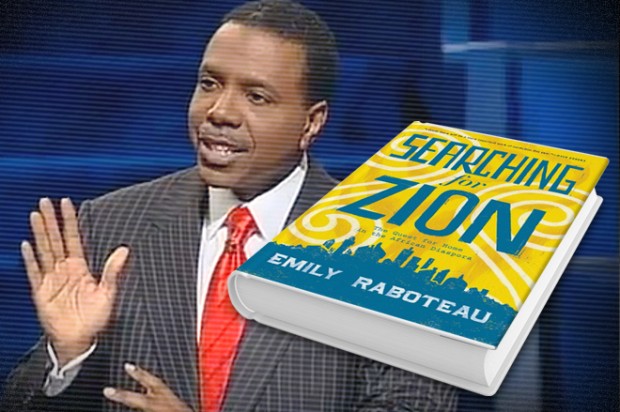

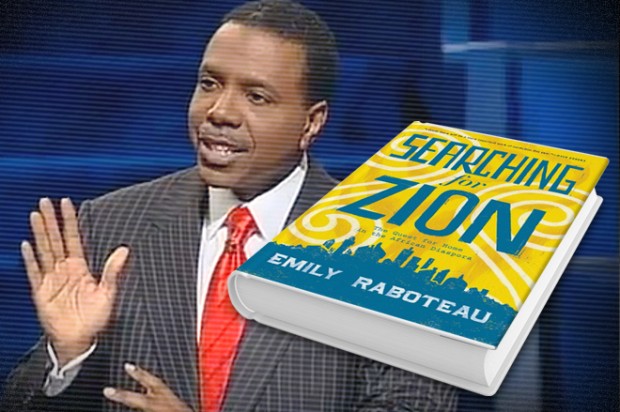

Thanks to Ralph Luker for pointing me towards this remarkable piece, "My Search for Creflo Dollar," by Emily Raboteau, whose father Albert Raboteau will need no introduction for the audience of this blog. A little excerpt below, which points to Emily's book Searching for Zion: The Search for Home in the African Diaspora, now definitely on my to-read list:

By shilling money as the thing that mattered most, men like Creflo Dollar, I complained to Victor, were cheapening our rich history of liberation theology, messing with the prophetic kind of faith that drove the Civil Rights Movement, our nation’s proudest moment. My father taught a seminar on the religious history of that movement and these were themes he’d discussed with me for as long as I could remember. He’d grown up during that ennobling period. He was nearly the same age as Emmett Till would be if he hadn’t been bludgeoned to death and dumped in a Mississippi river at age fourteen for talking to a white woman. This was the backdrop against which my parents met at a Catholic university in Milwaukee in the 1960s. There my father helped organize a student movement that pushed for more minority faculty hires and student enrollment. Along with two roommates, he led a protest that shut down the university for two weeks.

Perhaps, like many children, I had a romance with the time of my parents’ youth. Their heroes were Martin Luther King and Dorothy Day, whose Catholic Worker offered a moral critique of the country’s drive for wealth and comfort. Wealth was a spiritual hazard that flew in the face of social justice. And didn’t my hero, Bob Marley, say more or less the same thing? A belly could be full yet hungry. A full stomach didn’t ensure a full heart or a full life.

Perhaps, like many children, I had a romance with the time of my parents’ youth. Their heroes were Martin Luther King and Dorothy Day, whose Catholic Worker offered a moral critique of the country’s drive for wealth and comfort. Wealth was a spiritual hazard that flew in the face of social justice. And didn’t my hero, Bob Marley, say more or less the same thing? A belly could be full yet hungry. A full stomach didn’t ensure a full heart or a full life.

Creflo Dollar’s church attracts some forty thousand members, most of them poor and working-class blacks trying to pull themselves out of poverty and into the middle class. They’re drawn by Dollar’s lavish lifestyle, his optimism, and his instruction of the Bible as a manual for prosperity. We are in control of our destiny, he teaches. We are already in the Promised Land. This is our home. We built it. It is ours.

Soon enough, I, too, was mesmerized. More than that — I was hooked. Beneath the mustache, thick as a Band-Aid, the smile had a blinding wattage. The big teeth didn’t look natural, and neither did his perfectly even hairline. His linebacker’s shoulders were a holdover from his college days as a star football player. You don’t build a ministry that takes in seventy million untaxed dollars a year from tens of thousands of members worldwide without charisma. Even after Victor fell asleep on the loveseat, I kept watching deep into the night, held by the flickering blue light of the ridiculously oversized flat-screen TV before us, trying to unravel Dollar’s message.

Thanks to Ralph Luker for pointing me towards this remarkable piece, "My Search for Creflo Dollar," by Emily Raboteau, whose father Albert Raboteau will need no introduction for the audience of this blog. A little excerpt below, which points to Emily's book Searching for Zion: The Search for Home in the African Diaspora, now definitely on my to-read list:

By shilling money as the thing that mattered most, men like Creflo Dollar, I complained to Victor, were cheapening our rich history of liberation theology, messing with the prophetic kind of faith that drove the Civil Rights Movement, our nation’s proudest moment. My father taught a seminar on the religious history of that movement and these were themes he’d discussed with me for as long as I could remember. He’d grown up during that ennobling period. He was nearly the same age as Emmett Till would be if he hadn’t been bludgeoned to death and dumped in a Mississippi river at age fourteen for talking to a white woman. This was the backdrop against which my parents met at a Catholic university in Milwaukee in the 1960s. There my father helped organize a student movement that pushed for more minority faculty hires and student enrollment. Along with two roommates, he led a protest that shut down the university for two weeks.

Perhaps, like many children, I had a romance with the time of my parents’ youth. Their heroes were Martin Luther King and Dorothy Day, whose Catholic Worker offered a moral critique of the country’s drive for wealth and comfort. Wealth was a spiritual hazard that flew in the face of social justice. And didn’t my hero, Bob Marley, say more or less the same thing? A belly could be full yet hungry. A full stomach didn’t ensure a full heart or a full life.

Perhaps, like many children, I had a romance with the time of my parents’ youth. Their heroes were Martin Luther King and Dorothy Day, whose Catholic Worker offered a moral critique of the country’s drive for wealth and comfort. Wealth was a spiritual hazard that flew in the face of social justice. And didn’t my hero, Bob Marley, say more or less the same thing? A belly could be full yet hungry. A full stomach didn’t ensure a full heart or a full life.

But Victor only laughed. “What’s so funny?” I asked him.

“Darlin’, I love you. I do. But you have the most convoluted way of trying to know your father.”

“I’m not talking about my father,” I insisted. “I’m talking about the problem of Creflo Dollar.”

“Okay,” Victor humored me. “Why should black people be holier than anyone else just because we’ve suffered? Why shouldn’t we want the same comforts everybody wants, in the end? A mortgage, a car, a retirement plan?”

Creflo Dollar’s church attracts some forty thousand members, most of them poor and working-class blacks trying to pull themselves out of poverty and into the middle class. They’re drawn by Dollar’s lavish lifestyle, his optimism, and his instruction of the Bible as a manual for prosperity. We are in control of our destiny, he teaches. We are already in the Promised Land. This is our home. We built it. It is ours.

Soon enough, I, too, was mesmerized. More than that — I was hooked. Beneath the mustache, thick as a Band-Aid, the smile had a blinding wattage. The big teeth didn’t look natural, and neither did his perfectly even hairline. His linebacker’s shoulders were a holdover from his college days as a star football player. You don’t build a ministry that takes in seventy million untaxed dollars a year from tens of thousands of members worldwide without charisma. Even after Victor fell asleep on the loveseat, I kept watching deep into the night, held by the flickering blue light of the ridiculously oversized flat-screen TV before us, trying to unravel Dollar’s message.

As a preacher, his trick was the power of positive thinking. As a motivational speaker, his trick was the Bible. As CEO, his trick was a wily concoction of both: self-help and Jesus Christ. It was a winning combination. Dollar’s product almost couldn’t lose, and his delivery was pitch-perfect. He was plainspoken, corporate, encouraging. He could sound like a Holy Roller and Oprah Winfrey in the same breath: “Get lack and insufficiency off your mind,” he urged. “Get satisfied. The Lord shall increase you more and more. I believe that when you get increase on your mind, you’re gonna receive increase in your life, and when you sow and give into the kingdom of God, it will trigger increase. Pray about sowing into this ministry and experience increase. It’s time to reap your crop.”

I was remarkably drawn to this snake oil salesman who used increase more often as a noun than a verb. A lot of what he said made sense. Just as he could sound like the Bible-thumping Pentecostal preacher Oral Roberts, whom he counted as a close friend, he could also sound like the black nationalist Malcolm X, who criticized the docility of the black church. Against my better judgment, I got sucked into a Black Entertainment Television wormhole — I followed Dollar’s show religiously and then began watching other black televangelists too. These men were slick. There was Bishop Eddie Long, whose Georgia mega-church pulled around twenty-five thousand members, and T.D. Jakes, with about thirty thousand in Texas. One night Jakes recounted a visit to a Johannesburg museum where he encountered a proverb on the wall: “When the Dutch came, we owned the land and they had the Bible. When they left, they owned the land and we had the Bible.” He asked his congregation one vital question: Why couldn’t they have both?

Comments