Of Intolerance, Hate Crimes, and Beards: Boundaries of Inclusion and Tolerance in American History and the American Present

Today's guest post is from Barton E. Price, a Visiting Assistant Professor of History at Grand Valley State University. He would like to thank his students for indulging his interests in these disparate topics and having discussions about them.

The last two weeks have been momentous ones for the history of American religious tolerance and intolerance, in case

you missed it. Thursday the 20th marked the one-year anniversary of

the repeal of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.

In this landmark reversal, homosexuals were allowed participation in the

military without fear of being “outed” and then discharged. The anniversary of

this repeal prompted me to think about other important decisions that have an

effect on American society. Namely, I am drawn to think about the intersection

of religion, American history, and individual civil rights.

In Maryland, there is a referendum to legalize

(or not) gay marriages in this state. As I see it, the issue of gay marriage

boils down to a basic civil rights question. Do homosexual persons have the

same rights and privileges accorded to them as citizens of the United States

regardless of their sexual identity? I think that the rights of citizens are an

ironclad guarantee so long as those persons are not criminals or enemies of the

state. I do not see how homosexuals fit either of those criteria on the basis

of their sexuality. So, it would seem to me that the logical answer to my

question is that yes homosexuals should have the legal protection to marry. I

do not see this issue as a religious one. Nor should it be.

But the Maryland case is an interesting one because it

invites us to think about religion and civil rights. I recall months ago

watching the news and hearing proponents of legalizing gay marriage claim that

this legalization would be a continuation of the arc of justice in Maryland

since the Act of Toleration in 1649

(interestingly enough, it was passed September 21, 1649). I chuckled to myself,

as I had just covered that document in American History to 1877 course. As it

turns out, the Act of Toleration is not a good example to use to support the

case for same-sex marriage. If one reads the document closely, it appears to be

a seventeenth-century version of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.

Speaking of Toleration, or rather intolerance, the senate

held its hearing on the shooting

at a Sikh temple as a hate crime. This hearing commenced on Wednesday, the 19th.

Like many, I was horrified to hear about the deaths of Sikhs. Equally

horrifying was that persistent Islamophobia

undergirded the assailant’s attack. Page’s mistake in incorrectly identifying

Sikhs as Muslims is unfortunate, and I have to say that I do not condone

attacks on anyone on account of their religious identification. But this is not

the first time that Sikhs have been wrongly identified according to racial and

religious markers.

In my Intro to American Civilization class this semester, we

studied a unit on the history of naturalization and citizenship. One common

theme we discussed was race and ethnicity (e.g. Chinese Exclusion Act, National

Origins Act). I also gave them case law from the Supreme Court. One case in

particular fascinated me as I was preparing my course in early August. That is

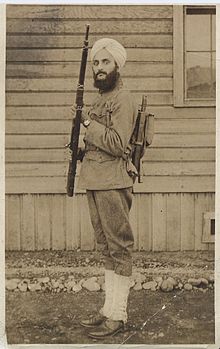

the case of Bhagat Singh Thind, an

immigrant to the United States from Punjab. He had served the U.S. in World War

I, had attended UC Berkeley, and was otherwise an upstanding member of society.

According to naturalization laws in 1917 that granted citizenship to Native

Americans if they served in the military, Thind applied for citizenship. He was

denied on account of his race. The case goes that Thind argued that he was

white (a qualifier in all naturalization laws since 1790) because he was of

Caucasian ethnicity. He had legal precedent to support this claim. The previous

year, the Supreme Court decided in Ozawa that a Japanese immigrant—while

having light skin—was not white because he was not Caucasian. Thind’s lawyer

thought that he had a tight case. Thind lost. The court determined that white

and Caucasian were exclusively the domains of people from northwestern Europe

and their descendents in the American continents. As appalling as this decision

is, it is even more appalling when we consider that the court declined to

recognize Thind’s actual religious tradition. Thind was a Sikh. The court,

however, stated:

In my Intro to American Civilization class this semester, we

studied a unit on the history of naturalization and citizenship. One common

theme we discussed was race and ethnicity (e.g. Chinese Exclusion Act, National

Origins Act). I also gave them case law from the Supreme Court. One case in

particular fascinated me as I was preparing my course in early August. That is

the case of Bhagat Singh Thind, an

immigrant to the United States from Punjab. He had served the U.S. in World War

I, had attended UC Berkeley, and was otherwise an upstanding member of society.

According to naturalization laws in 1917 that granted citizenship to Native

Americans if they served in the military, Thind applied for citizenship. He was

denied on account of his race. The case goes that Thind argued that he was

white (a qualifier in all naturalization laws since 1790) because he was of

Caucasian ethnicity. He had legal precedent to support this claim. The previous

year, the Supreme Court decided in Ozawa that a Japanese immigrant—while

having light skin—was not white because he was not Caucasian. Thind’s lawyer

thought that he had a tight case. Thind lost. The court determined that white

and Caucasian were exclusively the domains of people from northwestern Europe

and their descendents in the American continents. As appalling as this decision

is, it is even more appalling when we consider that the court declined to

recognize Thind’s actual religious tradition. Thind was a Sikh. The court,

however, stated:

“It is a matter of familiar observation and knowledge

that the physical group characteristics of the Hindus render them readily

distinguishable from the various groups of persons in this country commonly

recognized as white.”

I’m not exactly sure what “physical group characteristics”

the court had in mind. My best guess would be the turban and beard.

Nevertheless, this case—and the shooting in Wisconsin—point to a longstanding

misunderstanding of Sikh religious identity vis-à-vis their Hindu and Muslim

neighbors.

Lastly, speaking of intolerance, hate crimes, and beards, on

Thursday the 20th, the jury in a federal court found seventeen Amish men guilty

of hate crimes for shaving off the beards of other Amish men. Interestingly

enough, the suspects were tried in accordance with the Matthew Shepherd Hate

Crimes Act.

This is not just a curiosity. Instead it invites us to think

about embodied religious practices (including facial hair), masculinity, and

the role of the law in handling religious disputes. The prosecutor was quoted

last fall saying that religious disputes over ideas handled in a sharing of

words was acceptable. But acts of physical violence in these disputes was not.

Are we to assume that the courts are—once again—taking on the role of defining

religious practice? It would appear so. This case offers us a new avenue to

explore some of these important themes. I call dibs.

So, these last few weeks have been important as we continue to

think about religion, race, ethnicity, and sexuality. As historians, we must

consider the contingencies, contexts, and continuities of limited tolerance in

America’s past and work to reveal those limitations if we are to push the

boundaries of inclusion.

Comments