The Genesis of Jesus Rock: An Interview with David W. Stowe

Randall Stephens

David W. Stowe is a professor of American Studies and Religious Studies at Michigan State University. He has written on jazz history, hymns, and rock music. Stowe is the author of a wide range of books and articles, including Swing Changes: Big-Band Jazz in New Deal America (Harvard University Press, 1996); How Sweet the Sound: Music in the Spiritual Lives of Americans (Harvard University Press, 2004); and, most recently, No Sympathy for the Devil: Christian Pop Music and the Transformation of American Evangelicalism (University of North Carolina Press, 2011). Below I interview Stowe about his excellent new book and his insights into Jesus rock and the culture of conservative evangelicalism.

Americans (Harvard University Press, 2004); and, most recently, No Sympathy for the Devil: Christian Pop Music and the Transformation of American Evangelicalism (University of North Carolina Press, 2011). Below I interview Stowe about his excellent new book and his insights into Jesus rock and the culture of conservative evangelicalism.

Randall Stephens: What drew you to the topic of the roots of Christian rock?

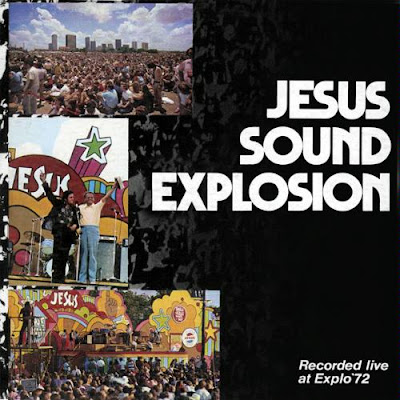

David W. Stowe: I was intrigued by the historical moment of the early Seventies—1971 to be exact—when it seemed popular music and youth culture were saturated in allusions to Jesus Christ: Godspell, Jesus Christ Superstar, several Top 40 songs with Jesus in their titles or verses. Why had the Son of God seemingly taken over U.S. popular culture at just that moment—when the countercultural energies of the Sixties were metamorphosing into something new? And did this music play some role in reshaping American culture during the Age of Reagan and beyond?

These struck me as questions worth trying to answer. There was a personal angle as well. I came of age during the Seventies and have always been fascinated by that decade, which I remember now as if it were some kind of dream. So Christian pop music—of which I was completely oblivious until about 15 years ago—was a lens through which to make sense of that strange interlude between Kent State and the Reagan Revolution.

Stephens: Why did a Christian analogue to rock music develop when and where it did?

Stowe: Like many forms of the Sixties counterculture, Christian rock first emerged in California. More precisely Orange County, the epicenter of what was dubbed the Jesus Movement. It was at Calvary Chapel in Costa Mesa where Chuck Smith famously teamed up with über-Jesus freak Lonnie Frisbee. Larry Norman came out of the Bay Area and had a major impact as well. But it’s important to note that the West Coast didn’t have a monopoly on Jesus music. The Rez Band (still in business) originated in

Milwaukee and made a very successful debut run across the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. CCM guitar hero Phil Keaggy did a stint at Love Inn in upstate New York. [Check out the McCartney, Ram-esque Keaggy song in the youtube clip here.] So this Jesus Movement—and the music that went with it—was a national phenomenon.

Stephens: You focus quite a bit of attention on apocalypticism. How did end-times views shape Christian rock and, even, politics?

Stowe: Apocalyptic themes had bounced around in American pop music since early Dylan—“A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”—and Barry McGuire’s surprise number-one hit of 1965, “Eve of Destruction.” A sense of living in end times tinged the late Sixties counterculture—a certain Cold War fatalism permeated American society for decades--so it made sense that an apocalyptic mindset would filter into the Jesus Movement. Among other things, it makes a catchy theme for a lyric. Witness Larry Norman’s most famous song: “Children died, the days grew cold/A piece of bread could buy a bag of gold/I wish we’d all been ready. . . .”

It didn’t hurt that these messages were being reinforced by the best-selling book of the seventies, Hal Lindsey’s Late Great Planet Earth. Politically, end-times prophecy tends to work against social and political movements, reformist or revolutionary. What’s the point of transforming the world if God is going to bring the curtain down on the whole sorry human enterprise? So most of the Jesus Freaks—and the musicians they listened to—focused on saving as many souls as they could before the Rapture.

Stephens: By concentrating on artists who were crossover, or more mainstream performers—like Al Green, Bob Dylan, and Aretha Franklin—you extend what most people might think of as Christian music or Christian rock. I wonder if you might say something about the tensions that existed between those who reached a larger, mainstream market and those who were fairly fixed within the Christian genre.

Stowe: This tension was one of the most intriguing aspects of the Christian pop phenomenon. On the one hand, the Jesus Movement tried to cast a wide net and welcome as diverse a following as possible. On the other hand, its theology was quite orthodox. There was a deep suspicion of alternate spiritualities of the kind that were floating around pop music especially after the Beatles went off to the Maharishi’s ashram at Rishikesh. Many of the decade’s most successful artists, whose music invoked religious and Christian themes—the ones you’ve mentioned, but also Marvin Gaye, Earth Wind & Fire, Stevie Wonder, even Johnny Cash—weren’t embraced by the Jesus Movement. Jesus freaks pretty much ignored them. From a broader historical perspective, thoug h, it was important to make sense of their relation to the baby boom evangelicals who were cutting their spiritual teeth in those years.

h, it was important to make sense of their relation to the baby boom evangelicals who were cutting their spiritual teeth in those years.

Stephens: Could you describe how you think Christian rock has changed since its early days in the late 1960s and early 1970s?

Stowe: It’s become both much more commercially slick and much more musically diverse. In the early days, Christian rock was mostly folk-rock, or just plain folk. Even hard rock was a bit of a stretch. Now one can find every genre of pop music represented in CCM: hardcore, hip-hop, punk, Goth, Norwegian death metal. CCM is now a very large and profitable market genre—outselling jazz and classical combined—so the promotion and production value of the music has gone way up. It’s theology tends to be much more eclectic as well. As I argued in the New York Times last spring, the innocently promiscuous mixing of Christian language in “secular” music doesn’t happen as it did during the early years of Christian rock; the secular/sacred divide seems to have hardened. Although, as is always the case when generalizing about a huge diverse culture form like popular music, important exceptions can be found.

Stephens: What projects are you currently working on?

Stowe: A short book on the varied forms Psalm 137 has taken in North America. That’s the one that begins, “By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, yea, we wept, when we remembered Zion. . . . How shall we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land?” I call it American’s longest-running protest song. Its history stretches from the earliest Pilgrim psalters through adaptation to the American Revolution, abolitionist movement, Harlem Renaissance, civil rights movement, and the widely covered reggae version, “Rivers of Babylon.” It’s a good lens for thinking about the varied social and political uses to which a thirteen-verse Hebrew poem can be put, and the endless inventiveness of music to wrap itself around ideology.

David W. Stowe is a professor of American Studies and Religious Studies at Michigan State University. He has written on jazz history, hymns, and rock music. Stowe is the author of a wide range of books and articles, including Swing Changes: Big-Band Jazz in New Deal America (Harvard University Press, 1996); How Sweet the Sound: Music in the Spiritual Lives of

Americans (Harvard University Press, 2004); and, most recently, No Sympathy for the Devil: Christian Pop Music and the Transformation of American Evangelicalism (University of North Carolina Press, 2011). Below I interview Stowe about his excellent new book and his insights into Jesus rock and the culture of conservative evangelicalism.

Americans (Harvard University Press, 2004); and, most recently, No Sympathy for the Devil: Christian Pop Music and the Transformation of American Evangelicalism (University of North Carolina Press, 2011). Below I interview Stowe about his excellent new book and his insights into Jesus rock and the culture of conservative evangelicalism.Randall Stephens: What drew you to the topic of the roots of Christian rock?

David W. Stowe: I was intrigued by the historical moment of the early Seventies—1971 to be exact—when it seemed popular music and youth culture were saturated in allusions to Jesus Christ: Godspell, Jesus Christ Superstar, several Top 40 songs with Jesus in their titles or verses. Why had the Son of God seemingly taken over U.S. popular culture at just that moment—when the countercultural energies of the Sixties were metamorphosing into something new? And did this music play some role in reshaping American culture during the Age of Reagan and beyond?

These struck me as questions worth trying to answer. There was a personal angle as well. I came of age during the Seventies and have always been fascinated by that decade, which I remember now as if it were some kind of dream. So Christian pop music—of which I was completely oblivious until about 15 years ago—was a lens through which to make sense of that strange interlude between Kent State and the Reagan Revolution.

Stephens: Why did a Christian analogue to rock music develop when and where it did?

Stowe: Like many forms of the Sixties counterculture, Christian rock first emerged in California. More precisely Orange County, the epicenter of what was dubbed the Jesus Movement. It was at Calvary Chapel in Costa Mesa where Chuck Smith famously teamed up with über-Jesus freak Lonnie Frisbee. Larry Norman came out of the Bay Area and had a major impact as well. But it’s important to note that the West Coast didn’t have a monopoly on Jesus music. The Rez Band (still in business) originated in

Stephens: You focus quite a bit of attention on apocalypticism. How did end-times views shape Christian rock and, even, politics?

Stowe: Apocalyptic themes had bounced around in American pop music since early Dylan—“A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”—and Barry McGuire’s surprise number-one hit of 1965, “Eve of Destruction.” A sense of living in end times tinged the late Sixties counterculture—a certain Cold War fatalism permeated American society for decades--so it made sense that an apocalyptic mindset would filter into the Jesus Movement. Among other things, it makes a catchy theme for a lyric. Witness Larry Norman’s most famous song: “Children died, the days grew cold/A piece of bread could buy a bag of gold/I wish we’d all been ready. . . .”

It didn’t hurt that these messages were being reinforced by the best-selling book of the seventies, Hal Lindsey’s Late Great Planet Earth. Politically, end-times prophecy tends to work against social and political movements, reformist or revolutionary. What’s the point of transforming the world if God is going to bring the curtain down on the whole sorry human enterprise? So most of the Jesus Freaks—and the musicians they listened to—focused on saving as many souls as they could before the Rapture.

Stephens: By concentrating on artists who were crossover, or more mainstream performers—like Al Green, Bob Dylan, and Aretha Franklin—you extend what most people might think of as Christian music or Christian rock. I wonder if you might say something about the tensions that existed between those who reached a larger, mainstream market and those who were fairly fixed within the Christian genre.

Stowe: This tension was one of the most intriguing aspects of the Christian pop phenomenon. On the one hand, the Jesus Movement tried to cast a wide net and welcome as diverse a following as possible. On the other hand, its theology was quite orthodox. There was a deep suspicion of alternate spiritualities of the kind that were floating around pop music especially after the Beatles went off to the Maharishi’s ashram at Rishikesh. Many of the decade’s most successful artists, whose music invoked religious and Christian themes—the ones you’ve mentioned, but also Marvin Gaye, Earth Wind & Fire, Stevie Wonder, even Johnny Cash—weren’t embraced by the Jesus Movement. Jesus freaks pretty much ignored them. From a broader historical perspective, thoug

h, it was important to make sense of their relation to the baby boom evangelicals who were cutting their spiritual teeth in those years.

h, it was important to make sense of their relation to the baby boom evangelicals who were cutting their spiritual teeth in those years.Stephens: Could you describe how you think Christian rock has changed since its early days in the late 1960s and early 1970s?

Stowe: It’s become both much more commercially slick and much more musically diverse. In the early days, Christian rock was mostly folk-rock, or just plain folk. Even hard rock was a bit of a stretch. Now one can find every genre of pop music represented in CCM: hardcore, hip-hop, punk, Goth, Norwegian death metal. CCM is now a very large and profitable market genre—outselling jazz and classical combined—so the promotion and production value of the music has gone way up. It’s theology tends to be much more eclectic as well. As I argued in the New York Times last spring, the innocently promiscuous mixing of Christian language in “secular” music doesn’t happen as it did during the early years of Christian rock; the secular/sacred divide seems to have hardened. Although, as is always the case when generalizing about a huge diverse culture form like popular music, important exceptions can be found.

Stephens: What projects are you currently working on?

Stowe: A short book on the varied forms Psalm 137 has taken in North America. That’s the one that begins, “By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, yea, we wept, when we remembered Zion. . . . How shall we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land?” I call it American’s longest-running protest song. Its history stretches from the earliest Pilgrim psalters through adaptation to the American Revolution, abolitionist movement, Harlem Renaissance, civil rights movement, and the widely covered reggae version, “Rivers of Babylon.” It’s a good lens for thinking about the varied social and political uses to which a thirteen-verse Hebrew poem can be put, and the endless inventiveness of music to wrap itself around ideology.

Comments

http://tinyurl.com/rockandrollhistoryscope

Another rich conversation about Jesus people and their music generated by your book, David! I also loved the music clip, "what a day." Next time "By the rivers of Babylon" which is a great project indeed.