The Soul Destroying Poison of the East; or, Why I'll Assume the Savasana Posture while Watching Mad Men

Paul Harvey

I’ve been meaning to get back to doing some yoga, something I did in years past, as a supplement to my normal exercise diet of web-surfing, Netflix-watching, fantasy-football-playing, and martini-glass-lifting. Every time I think of doing so, however, the same chilling thought comes to mind: what will Matt Sutton say? All the trash talk sure to come my way via my gmail from said Sutton should I announce my resumption of yoga as my spiritual discipline and complaining about how I can’t even hold the “Warrior Pose” for more than five seconds, pins me to my chair.

Or maybe it’s just that I’m lazy and would rather just stick to my normal exercise diet, as described above. I report, you decide.

Yoga, and the nexus of yoga with religion, physical fitness, commerce, and sex in America has received much attention lately, probably due to the appearance of a number of recent books detailing the history of the yoga

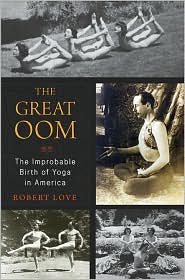

phenomenon. In this week’s New York Times Book Review (which, startlingly, actually had a number of well-written and engaging reviews which dealt at length and seriously with the subject matter at hand by people who knew something about the subject beforehand -- if only this would be more the norm), Pankaj Mishra reviews Stefanie Syman’s The Subtle Body: The Story of Yoga in America, and Robert Love’s The Great Oom: The Improbable Birth of Yoga in America. Barbara Spindel also has a nice review of both works together here. Love focuses more on Pierre Bernard, described by Mishra as “one of the first of many indefatigable charlatans who popularized yoga.” Read the reviews for more fascinating detail on yoga’s Elmer Gantry.

Syman’s work follows a broader track, beginning with the influence of Indian philosophy on the Transcendentalists:

Both Emerson and Thoreau admired the “Bhagavad-Gita”; Emerson’s Oversoul resembles the Brahman, the all-inclusive, all-pervading Self of the Upanishads. However, neither Emerson nor Thoreau knew much about the physical-fitness side of yoga. The earliest Indian vendors of spirituality, like Swami Vivekananda, who lectured on Hinduism at the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago in 1893, looked down on the asanas, or poses, of hatha yoga as a defective path to yoga’s goal: the union of the individual self with the divine Self.

Syman then follows the appearance of Indian religious figures at the World Parliament of Religions in 1893, the struggles of yoga teachers and practitioners through the era of immigration restriction, and finally to the post-1945 recovery of yoga in America and its explosion with the counterculture and intense commercialization afterwards.

The story may appear to be a familiar one: the marketing of yet another religious tradition, and its watering down into a convenient calorie-burner for people on the go. Or at least for people who can tune out and turn off long enough to do so.

That’s certainly part of it, but Mishra points out that religious traditions, no matter how ancient, are always more mixed up than this, and that contemporary Americans were hardly the first to bring together religion, exercise, commerce, and sex:

The image of incorrigibly individualist and materialist Americans rummaging through ancient cultures in search of eternal youth, beauty and self-gratification has long provoked scorn. “Yoga in Mayfair or Fifth Avenue,” Carl Jung sternly declared, “is a spiritual fake.” But such a fetish of the “authentic” assumes that people in the country of yoga’s origin have upheld a timeless and unchanging yoga rather than practicing what Wendy Doniger, the distinguished historian of Hinduism, calls the world’s greatest “have your rice cake and eat it” religion.

It was in India that the tradition of Tantrism first exalted the human body as the source of this-worldly liberation. The generation of semi-Westernized Indians who brought about the renaissance of yoga in the early 20th century were themselves syncretists, combining ideas from both East and West. Even the physical aspects that dominate yoga today are partly reimports from the West. T. Krishnamacharya (the South Indian teacher of Indra Devi), B. K. S. Iyengar and K. Pattabhi Jois borrowed from gymnastic postures introduced to India by British colonialists.

Reading all this may be just enough to get me back into the bikram studio just down the street (everyone, promise not to tell Sutton). For now, it’s time to assume the savasana (corpse) posture on my lounger, take the first previous sip of an appropriately dry martini, and fire up some Mad Men. Now that’s what I’m talking about.

Comments

I'm always intrigued by any debate about "authenticity," because that means there's always something bigger at stake. In the case of yoga, the idea of a materialist West versus a spiritual East was not confined to Americans searching for truth in Hindu practice. In one of my favorite of his quotes, Vivekananda once said something to the effect of "America is a land with lots of money but no spirituality, India is rich in spirit but poor in money. So, I come from India and give Americans spirituality and they give me money." Not only is the image of the Westerner rummaging through ancient religions and cherry-picking practices essentialist, as Mishra points out, it also neglects the agency of Hindus who, for various reasons, were quite happy to offer Americans "Asian spirituality."

Also glad to see more books on early (pre-'65) Hinduism in America. Makes me feel a little more relevant. Only slightly.

P.S. I love mad men!