The Colored Embalmer: Homegoings, Capitalism, and African American Civil Rights

Paul Harvey

Paul HarveyLet's move from the ridiculous (see yesterday's post) to the sublime:

A really fine new book to recommend, more about religious history than I would have guessed initially: Suzanne E. Smith, To Serve the Living: Funeral Directors and the African American Way of Death.

I always like it when a book tells me about a subject I presumed to know a fair deal about, but (as it turns out), as I read along I realize the half ain't never been told. This is one of those books.

First, a more general summary, then I'll focus a bit on the parts that most intersect with this blog's interests. "Throughout African American history, death and funerals have been inextricably intertwined with life and freedom,” Smith writes in this vigorously argued survey of African American death “homegoing” practices from slavery to the twenty-first century. Smith provides fascinating details about diverse subjects while mounting an important argument about the central paradox of black funeral home direction: “that one needed to both fight racial discrimination and cultivate race patronage.” The author explores the role of the black funeral

home industry in twentieth century black capitalism, and the central place behind the scenes of black funeral home directors in the civil rights movement. From the key role of black funeral director pioneer Preston Taylor in organizing a boycott of segregated streetcars in early twentieth century Nashville, to the Floridian Robert Miller’s sponsorship of Mahalia Jackson’s early career (when she sang for $2.00 a funeral), to the famously public viewing of the mutilated body of Emmitt Till in Mississippi, to black tycoon E. G. Gaston’s mediation during the crusade in Birmingham, Alabama in 1963, black morticians have quite literally embodied African American history.

home industry in twentieth century black capitalism, and the central place behind the scenes of black funeral home directors in the civil rights movement. From the key role of black funeral director pioneer Preston Taylor in organizing a boycott of segregated streetcars in early twentieth century Nashville, to the Floridian Robert Miller’s sponsorship of Mahalia Jackson’s early career (when she sang for $2.00 a funeral), to the famously public viewing of the mutilated body of Emmitt Till in Mississippi, to black tycoon E. G. Gaston’s mediation during the crusade in Birmingham, Alabama in 1963, black morticians have quite literally embodied African American history.Now, a few notes more specific to this blog's interests. The early parts of the work, in a chapter entitled "From Hush Harbors to Funeral Parlors," discuss the origins and meanings of slave funerals, and the close connection of funeral practices and rites with the origins of African American churches. The connection between those two remains in focus through the books. White authorities certainly recognized the potential threat posed by this. Hence, they surveiled black funerals, and dishonored/mutilated the bodies of black rebels. The black funeral tradition came about in part as a means to honor bodies that had been dishonored in life.

In the post-civil war years, as the new science of embalming and other techniques took hold, the black funeral industry grew up, providing embalming/funeral services to a black clientele. In 1888, Preston Taylor, a former slave and Baptist minister in Nashville, opened Taylor and Company Undertakers and later created Greenwood Cemetery (which white authorities later tried to close down) "to provide Nashville's black citizens with a dignified burial ground." In the early twentieth century, Taylor teamed with Richard H. Boyd, founder of the largest black-owned publishing house (the National Baptist Publishing Board) in the country, to organize a boycott of Nashville's newly segregated streetcars, and to organize an independent streetcar operation. Here, black funeral homes and churches were intertwined in providing the capital and the personnel for early freedom struggles in the Jim Crow era, a theme that will reappear throughout the book.

In a chapter entitled "My Man's An Undertaker" (from a clever Dinah Washington song) Smith follows the close connection of black funerals and the early history of black gospel. Robert Miller, first president of the Independent National Funeral Directors' Association (INFDA, the nationwide trade organization for black funeral directors, who were not allowed to join the equivalent national organization for whites), drove Mahalia Jackson around in his hearse to her early singing engagements, and hired her to sing at funerals, where the emotional depths of the music could be fully expressed. Funeral directors also "sponsored gospel music radio shows as a way to promote the music and tastefully advertise their services."

In a chapter entitled "My Man's An Undertaker" (from a clever Dinah Washington song) Smith follows the close connection of black funerals and the early history of black gospel. Robert Miller, first president of the Independent National Funeral Directors' Association (INFDA, the nationwide trade organization for black funeral directors, who were not allowed to join the equivalent national organization for whites), drove Mahalia Jackson around in his hearse to her early singing engagements, and hired her to sing at funerals, where the emotional depths of the music could be fully expressed. Funeral directors also "sponsored gospel music radio shows as a way to promote the music and tastefully advertise their services."As the funeral industry and the number of black undertakers grew, so did allegations (sometimes justified) of price-gouging, fraud, and hucksterism. The shyster undertaker came to have a reputation akin to that of the jackleg preacher. Each was dependent upon, and learned to exploit, a captive audience, enriching himself in the process. Miller and other figures in the INFDA fought to preserve the reputation of their industry. At the same time, their industry basically depended on a segregated economy, and it was the official policy of the black undertakers' organization to actively discourage white competitors from seeking out black bodies to service.

(A little off topic, but worth noting: the book has fascinating discussions of various black funeral directors' organizations and controversies within them, as well as a section about The Colored Embalmer, the first African American trade publication).

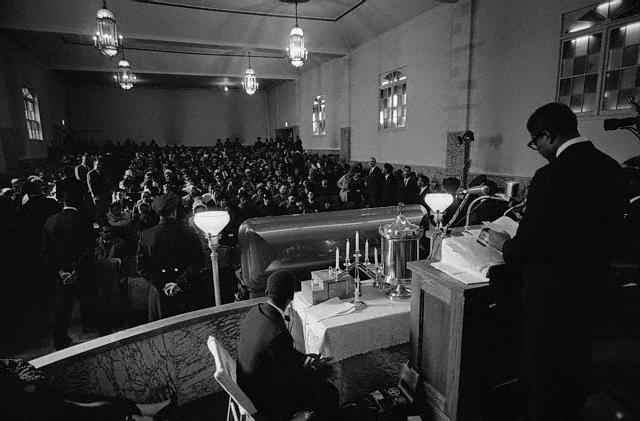

Black funeral directors proved instrumental during the civil rights years. They weren't usually in the public eye, but for that reason they could serve to provide meeting facilities, post bail, comfort the families of the murdered, and (at times) negotiate with white authorities from a position of strength. Black undertaker C. W. Lee, a funeral director in Montgomery, Alabama, served as treasurer of the Montgomery Improvement Association, and was instrumental in organizing financing for the Montgomery Bus Boycott. He and others in the civil rights era cemented the relationship between religion, race, and civil rights. As churches were bombed, funeral directors offered their facilities for civil rights organizing meetings, including one attended by James Farmer of CORE. Stuck in jail in Louisiana during the March on Washington in 1963, Farmer organized protests in Plaquemine that nearly resulted in his life; he managed to escape a lynch mob, using as his getaway vehicles two hearses from the local funeral home, which sped him out of town and on to New Orleans.

There's much more in the later chapters of the book, including extended discussions of the funerals of Malcolm X and Rosa Parks, as well as the fate of black funeral homes in recent years. Jessica Mitford's famous expose of the industry received surprisingly little discussion among black funeral home directors, who simply had more pressing matters to contend with in the 1960s. In the 1990s, the consolidation of the industry into mega-conglomerates challenged the role of independent black entrepreneurs, and gang shootings at funeral homes brought senseless death into places that historically had brought meaning to death. "Today," Smith concludes, "African American funeral directors continue to serve the living while burying the dead; in so doing, they continue to remind us of the role that death and funerals have always played in the long quest for freedom."

Comments