One Million Catholics Skip Mass

MICHAEL PASQUIER

It’s just a guess, but I think a good guess, that approximately one million Louisiana Catholics skipped mass last Sunday. Over 95% of the population of South Louisiana, or around 2 million people, spent the Sabbath packed into automobiles, queued at gas stations and Home Depots, laying on cots and loitering in parking lots of public shelters, or stuffed into the homes of relatives and hotel rooms in anticipation of Hurri cane Gustav’s landfall, to say nothing of the thousands of National Guardsmen and women, medical first-responders, law enforcement officers, and other civic leaders who stayed behind to oversee the evacuation and emergency response. Diocesan officials cancelled masses and urged their parishioners—about half the population of South Louisiana—to heed the advice of state and local governments to leave areas in the path of Gustav. No doubt, Hurricanes Katrina and Rita were on the minds of everyone.

cane Gustav’s landfall, to say nothing of the thousands of National Guardsmen and women, medical first-responders, law enforcement officers, and other civic leaders who stayed behind to oversee the evacuation and emergency response. Diocesan officials cancelled masses and urged their parishioners—about half the population of South Louisiana—to heed the advice of state and local governments to leave areas in the path of Gustav. No doubt, Hurricanes Katrina and Rita were on the minds of everyone.

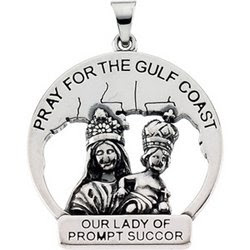

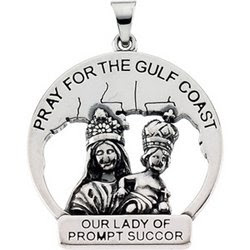

In the weeks and months leading up to Hurricane Gustav’s arrival on the morning of September 1, 2008—just three days after the third anniversary of Katrina and three weeks before the same anniversary of Rita—Catholic massgoers throughout the state recited a prayer to Our Lady of Prompt Succor, the Patroness of Louisiana, which read, “Our Father in heaven, through the powerful intercession of Our Lady of Prompt Succor, spare us from all harm during this hurricane season and protect us and our homes from all disasters of nature. Our Lady of Prompt Succor, hasten to help us. Amen.” The same prayer was recited in Catholic churches unaffected by evacuation orders on the day before Gustav landed, sometimes within eye-shot of highways and interstates streaming with many carloads of Catholics skipping mass.

Suffice it to say that Catholics living in Louisiana, from your regular churchgoer to the so-called lapsed variety, know that Our Lady of Prompt Succor is the Mary you pray to during hurricane season. Hear a story about the feastday celebration of OLPS on NPR here. It’s just one of those things that Louisiana Catholics do, like abstaining from the consumption of meat on Friday’s during Lent and gorging instead on crawfish, shrimp, and cheap beer. It’s also safe to say that most Louisiana Catholics—and historians of American religion for that matter—know very little about the history of the cult of Our Lady of Prompt Succor. I should know, I wrote a boring article on that very subject in the book Saints and Their Cults in the Atlantic World. Rebecca Carter’s article on “spiritual dwelling” in post-Katrina New Orleans in the Journal of Southern Religion is a better place to start thinking about personal devotions to Our Lady of Prompt Succor.

the Atlantic World. Rebecca Carter’s article on “spiritual dwelling” in post-Katrina New Orleans in the Journal of Southern Religion is a better place to start thinking about personal devotions to Our Lady of Prompt Succor.

After evacuating from my residence in South Louisiana and as I enjoyed the company and hospitality of friends and family 200 miles inland, I couldn’t help but think how inconsequential my historical knowledge of the cult of Our Lady of Prompt Succor was to what was going on in the minds of millions of Catholics and non-Catholics as they worried about running out of gas, finding and then paying for a hotel room, feeding and sheltering their children, and when they would be able to return to their homes that may be destroyed. It’s hard to imagine even the most devout Catholic grandmother from Plaquemines Parish—the southeastern most parish (county) of Louisiana lined by the levees of the Mississippi River—focusing intensely on the Mary that was supposed to protect her home and family from disaster. It’s hard to imagine anyone keeping attuned to what scholars generally consider “religious” concerns in the heat of the moment.

It’s this “religion-in-the-moment” that is perplexing for scholars like me who were raised on books like Robert Orsi’s The Madonna of 115th Street and Thomas Tweed’s Our Lady of the Exile, perhaps the two most influential studies of Marian devotionalism in America. The evidence and data used in these sorts of books, however magnificent, are usually disconnected from immediate experience, when devotees are pressed to fill out questionnaires, contrive quotes for inquisitive interviewers, or send anonymous petitions to shrine newsletters. I have a difficult time thinking of ways to situate the religious experiences of hurricane evacuees in historical, social, and cultural contexts. The circumstances just seem too aberrant, too disjointed from ordinary time and space, to capture the religious experiences of the moment. Scholars of religious studies, myself included, tend to use phrases like “lived religion” and “extraliturgical religion” to describe religion outside the carefully scripted confines of “official religion” or “institutional religion.” But these categories seem only to get at the before and after the storm; the now remains elusive. I can’t help but think—actually, I know—that I’m missing something. The scholar in me wants to know what it's like, but every other part of my being never wants to know.

usually disconnected from immediate experience, when devotees are pressed to fill out questionnaires, contrive quotes for inquisitive interviewers, or send anonymous petitions to shrine newsletters. I have a difficult time thinking of ways to situate the religious experiences of hurricane evacuees in historical, social, and cultural contexts. The circumstances just seem too aberrant, too disjointed from ordinary time and space, to capture the religious experiences of the moment. Scholars of religious studies, myself included, tend to use phrases like “lived religion” and “extraliturgical religion” to describe religion outside the carefully scripted confines of “official religion” or “institutional religion.” But these categories seem only to get at the before and after the storm; the now remains elusive. I can’t help but think—actually, I know—that I’m missing something. The scholar in me wants to know what it's like, but every other part of my being never wants to know.

It’s just a guess, but I think a good guess, that approximately one million Louisiana Catholics skipped mass last Sunday. Over 95% of the population of South Louisiana, or around 2 million people, spent the Sabbath packed into automobiles, queued at gas stations and Home Depots, laying on cots and loitering in parking lots of public shelters, or stuffed into the homes of relatives and hotel rooms in anticipation of Hurri

cane Gustav’s landfall, to say nothing of the thousands of National Guardsmen and women, medical first-responders, law enforcement officers, and other civic leaders who stayed behind to oversee the evacuation and emergency response. Diocesan officials cancelled masses and urged their parishioners—about half the population of South Louisiana—to heed the advice of state and local governments to leave areas in the path of Gustav. No doubt, Hurricanes Katrina and Rita were on the minds of everyone.

cane Gustav’s landfall, to say nothing of the thousands of National Guardsmen and women, medical first-responders, law enforcement officers, and other civic leaders who stayed behind to oversee the evacuation and emergency response. Diocesan officials cancelled masses and urged their parishioners—about half the population of South Louisiana—to heed the advice of state and local governments to leave areas in the path of Gustav. No doubt, Hurricanes Katrina and Rita were on the minds of everyone.In the weeks and months leading up to Hurricane Gustav’s arrival on the morning of September 1, 2008—just three days after the third anniversary of Katrina and three weeks before the same anniversary of Rita—Catholic massgoers throughout the state recited a prayer to Our Lady of Prompt Succor, the Patroness of Louisiana, which read, “Our Father in heaven, through the powerful intercession of Our Lady of Prompt Succor, spare us from all harm during this hurricane season and protect us and our homes from all disasters of nature. Our Lady of Prompt Succor, hasten to help us. Amen.” The same prayer was recited in Catholic churches unaffected by evacuation orders on the day before Gustav landed, sometimes within eye-shot of highways and interstates streaming with many carloads of Catholics skipping mass.

Suffice it to say that Catholics living in Louisiana, from your regular churchgoer to the so-called lapsed variety, know that Our Lady of Prompt Succor is the Mary you pray to during hurricane season. Hear a story about the feastday celebration of OLPS on NPR here. It’s just one of those things that Louisiana Catholics do, like abstaining from the consumption of meat on Friday’s during Lent and gorging instead on crawfish, shrimp, and cheap beer. It’s also safe to say that most Louisiana Catholics—and historians of American religion for that matter—know very little about the history of the cult of Our Lady of Prompt Succor. I should know, I wrote a boring article on that very subject in the book Saints and Their Cults in

the Atlantic World. Rebecca Carter’s article on “spiritual dwelling” in post-Katrina New Orleans in the Journal of Southern Religion is a better place to start thinking about personal devotions to Our Lady of Prompt Succor.

the Atlantic World. Rebecca Carter’s article on “spiritual dwelling” in post-Katrina New Orleans in the Journal of Southern Religion is a better place to start thinking about personal devotions to Our Lady of Prompt Succor.After evacuating from my residence in South Louisiana and as I enjoyed the company and hospitality of friends and family 200 miles inland, I couldn’t help but think how inconsequential my historical knowledge of the cult of Our Lady of Prompt Succor was to what was going on in the minds of millions of Catholics and non-Catholics as they worried about running out of gas, finding and then paying for a hotel room, feeding and sheltering their children, and when they would be able to return to their homes that may be destroyed. It’s hard to imagine even the most devout Catholic grandmother from Plaquemines Parish—the southeastern most parish (county) of Louisiana lined by the levees of the Mississippi River—focusing intensely on the Mary that was supposed to protect her home and family from disaster. It’s hard to imagine anyone keeping attuned to what scholars generally consider “religious” concerns in the heat of the moment.

It’s this “religion-in-the-moment” that is perplexing for scholars like me who were raised on books like Robert Orsi’s The Madonna of 115th Street and Thomas Tweed’s Our Lady of the Exile, perhaps the two most influential studies of Marian devotionalism in America. The evidence and data used in these sorts of books, however magnificent, are

usually disconnected from immediate experience, when devotees are pressed to fill out questionnaires, contrive quotes for inquisitive interviewers, or send anonymous petitions to shrine newsletters. I have a difficult time thinking of ways to situate the religious experiences of hurricane evacuees in historical, social, and cultural contexts. The circumstances just seem too aberrant, too disjointed from ordinary time and space, to capture the religious experiences of the moment. Scholars of religious studies, myself included, tend to use phrases like “lived religion” and “extraliturgical religion” to describe religion outside the carefully scripted confines of “official religion” or “institutional religion.” But these categories seem only to get at the before and after the storm; the now remains elusive. I can’t help but think—actually, I know—that I’m missing something. The scholar in me wants to know what it's like, but every other part of my being never wants to know.

usually disconnected from immediate experience, when devotees are pressed to fill out questionnaires, contrive quotes for inquisitive interviewers, or send anonymous petitions to shrine newsletters. I have a difficult time thinking of ways to situate the religious experiences of hurricane evacuees in historical, social, and cultural contexts. The circumstances just seem too aberrant, too disjointed from ordinary time and space, to capture the religious experiences of the moment. Scholars of religious studies, myself included, tend to use phrases like “lived religion” and “extraliturgical religion” to describe religion outside the carefully scripted confines of “official religion” or “institutional religion.” But these categories seem only to get at the before and after the storm; the now remains elusive. I can’t help but think—actually, I know—that I’m missing something. The scholar in me wants to know what it's like, but every other part of my being never wants to know.

Comments

Provocative because it forces us to think about the limits of scholarly inquiry. Frustrating because, unlike my pathetically small back yard, I have no sense of where these boundaries begin and end. Moreover, after protracted periods of puzzlement, I have no clear exit plan, no path for leaving this intellectual battlefield. So I’m reminded of Caroline Walker Bynum who wrote, “my understanding of the historian’s task precludes wholeness. Historians, like fishes of the sea, regurgitate fragments. Only supernatural power can reassemble fragments so completely that no particle of them is lost.” So perhaps capturing the moment isn't a goal at all. Rather, it's about picking up the pieces and giving others a small window into a much more complex series of events.

First, the Lady of Prompt Succor article is far from boring. How can anything about Our Lady of Quick Help be boring?

Second, your post makes me think that at least in dramatic moments of religious life people attempt to record how they felt. Granted, we cannot get to these moments, but they stay lodged in memory waiting to be narrated. This means that those mundane religious moments might be lost to historians more readily. We can remember how we felt in moments of crisis like Gustav, but how was our religious life on an average Tuesday? We need to narrate dramatic events, to tell our stories, so we can figure out exactly what happened. Lived religion moves us to understand how people recognize themselves and their religiosity. My worry is similar to yours Mike, but I feel like I can never to get to day by day experience. Why narrate such experiences? So perhaps, Art is right. We can only pick up fragments, but some of those fragments seem irretrievable. Those moments are lost because they are commonplace, but I would love to have a glimpse of what the mundane appears to be in religious life as well.

Great post, Mike, and thoughtful comments, Art.