"A Little Murder Goes A Long Way": Film and Sacrifice

BY KELLY BAKER

Our own Katie Lofton has contributed a fascinating, must-read piece, entitled, "Necessary Sacrifice: Sundance, Mormon Movies, and the Race to Oscar Night," to Religion Dispatches. Relying upon René Girard, she argues that we need these sacrifices, often horrific events, which is why we consume such violence. Violence appears in the headlines of CNN, on our television sets, and in the movie theater. This violence spurs us into dialogue with one another. Can you believe this? How could this happen?! How terrible is this? Or wow, I am glad that didn't happen to me! She points out that this dialogue is part of the process. We need this catharsis. (I evidently need this too, since I just started reading Alice Sebold's Lucky, her memoir of her rape as a college freshman. I am guilty as charged.) Katie writes:

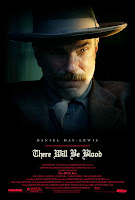

Violence interrupts domesticity, smearing the breakfast table with surprise blood. The audience gasped, sometimes, but mainly sat mutely. We were expecting the hairpin turn. We knew that no Sundance submission would linger in the long arc of romance or adventure, horror or crime. Contemporary filmic success relies on the unexpected shatter: Fido flailing in dark swimming holes, mama strapping on a shotgun to interrupt dad’s afternoon Laz-Z-Boy lookout. Take, as evidence, the 2008 Academy Award nominees for best picture: At onement glancing quickly at a once-upon-a-time (maybe) rape; Michael Clayton distracting with an exploding car and staged suicide; No Country For Old Men starring an impassive assassin who pauses only to wipe blood from his shoes on suburban porch steps; There Will Be Blood blending boyhood play and death by bowling. Even Juno includes a near-miss violation, with the saucy lead actress narrowly escaping fetal murder (and adulterous misdeed) by the sheer coincidence of her own ironic conscience (and a good long roadside cry). Films are populated with phlegmatic faces pressing past unbelievable slaughter, the onward momentum of man no matter the carcasses that collect. Films seeking prizes need only a sentimental tour of death and redemption, shocking interruption and inevitable survival.

onement glancing quickly at a once-upon-a-time (maybe) rape; Michael Clayton distracting with an exploding car and staged suicide; No Country For Old Men starring an impassive assassin who pauses only to wipe blood from his shoes on suburban porch steps; There Will Be Blood blending boyhood play and death by bowling. Even Juno includes a near-miss violation, with the saucy lead actress narrowly escaping fetal murder (and adulterous misdeed) by the sheer coincidence of her own ironic conscience (and a good long roadside cry). Films are populated with phlegmatic faces pressing past unbelievable slaughter, the onward momentum of man no matter the carcasses that collect. Films seeking prizes need only a sentimental tour of death and redemption, shocking interruption and inevitable survival.

Because they do, of course, all end with a smile. Or a clown’s tear. Michael Clayton smirking at the back of a cab; Juno grinning as her lover’s duet concludes; even Tommy Lee Jones stares, knowingly, into the desert beyond. Sundance didn’t spare us, either: the suicidal sister sits amiably for Kodak, and Dennis the muscle-bound German dims the bedside lamp. The Finnish farmer felon bakes a great baker’s dozen, and the murdering New Orleans refugees march, sodden, into sunset. The afterlife of violence is scabbed, dignified, chin-up-now survival. Sentimental schemes, one and all: we are convinced that something necessary has been expelled, that the sacrifice has worked. A little murder goes a long way.

Comments